By Ed Reynolds

By Ed Reynolds

Detective (ret.)

Historian, Phoenix Police Museum

The Deuce” was the area from Van Buren Street to Jackson Street, Central Avenue to 7th Street. It consisted of old flophouse hotels, cathouses and businesses like the Busy Bee Café, where many officers went for lunch and dinner. The businesses were mostly old two- and three-story buildings.

The infamous Paris Alley was located between Jefferson Street and Washington Street, approximately in the area of 2nd Street. Paris Alley was shaped like a “T.” Some of the more popular area businesses were Open Door Liquors and Rosita’s Mexican Food. These businesses all had alleys behind them, which were used for backdoor entrances, merchandise loading and unloading, and trash storage. It was not unusual back then for all the downtown alleys to have names, such as “French Alley” and “Gold Alley.” Everyone seems to know Paris Alley because of its location and all the very active businesses in the area.

Paris Alley is where the very last operable Phoenix P.D. call box was located. Call boxes were used for officers to phone headquarters, since early police car radios had one-way communication and could only receive calls. Also, portable police radios didn’t exist yet, so when walking beat officers were needed, a light lit up on police headquarters and signaled officers to call in right away. The key to the call box looked very similar to the current traffic box key. This same call box is now on display at the Phoenix Police Museum.

The Deuce was filled with half a dozen or more old, worn-out flophouses. There were no doors on the rooms, and each room contained about six to eight cots or sometimes just mattresses. The rooms were very inexpensive, and on a weekend, all spaces were taken.

On Friday and Saturday nights during harvest season, buses would bring in field workers to downtown Phoenix. The buses would unload and park on the streets, waiting to carry the laborers back out to the fields and orchards.

The downtown population would increase by the thousands during these weekends. Those arriving on the buses were mostly hardworking and hard-drinking Mexican males. The majority of arrests were for drunk and disorderly (D&D), vagrancy, loitering and disturbing the peace. Any annoying activity would fall into one of these charges. For most of those old-timers, those early experiences would leave some humorous stories to tell. Here’s a few:

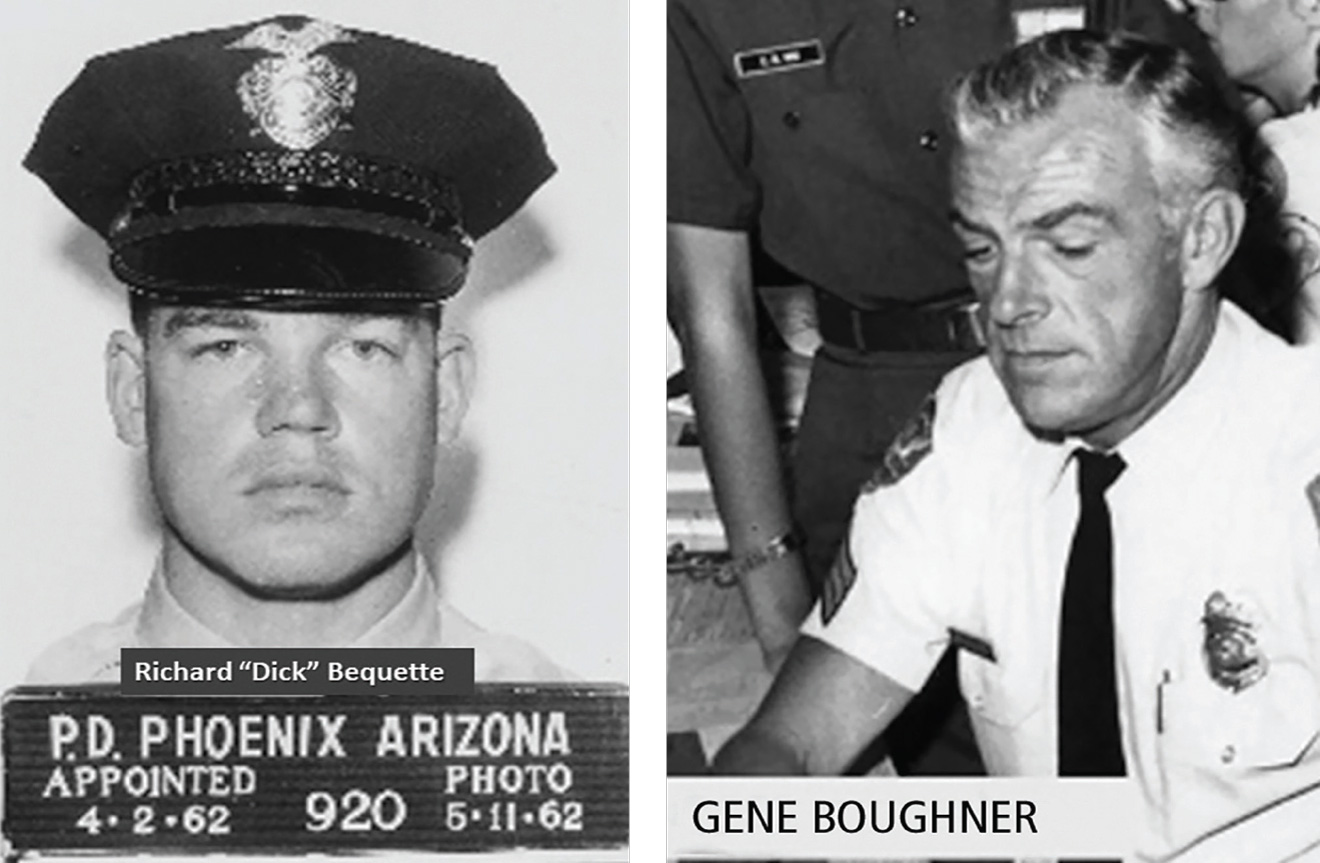

One day, while working in the Deuce, Dick Bequette and Gene Boughner arrested 16 people in the first part of their shift. They put every prisoner inside the paddy wagon, which was built to hold eight to 10 people. After filling the wagon, they drove to the station and backed down the “chute” to get them into the jail. They initially unloaded half of the prisoners and quickly booked them into the jail. This took approximately 30 to 45 minutes to accomplish, and they returned to the wagon, gathered up the other eight prisoners and took them up to the jail to be booked.

Sergeant Gus Oviedo Sr. was the desk sergeant that night. He was quite upset, madly complaining this was too many prisoners to be booking at once.

He definitely did not think it was as funny as Dick and Gene thought it was. Dick and Gene had handled so many filthy, stinking prisoners that night, they insisted on using the untouchable “green soap” to clean up afterward. This soap was an antiseptic hospital soap and quite expensive, but after searching all those prisoners, they wanted to clean up properly. The jail matron agreed and gave them the soap, despite the objections of Sergeant Oviedo. They left the jail and decided to have lunch before hitting the street again. After an enjoyable lunch at the Busy Bee Café, they hit the street and quickly arrested 16 more people and arrived at the chute again, just hours after the previous 16 arrests. Sergeant Oviedo had a conniption fit over their antics. The complaint he wrote up led to a new policy that no more than eight prisoners could be carried in a wagon at one time.

I remember back in the 1980s and early 1990s, an officer could make an arrest, have the booking paperwork done and the prisoner in the wagon in about 30 minutes. After becoming a detective in the l990s and seeing the paperwork increase and the booking procedures go crazy, I would rub it in to young patrolmen about how easy we had it “back in the day.” But never did I ever see anything like what Dick Bequette said he did back in the 1960s. He remembers a night when he and Gene Boughner were on Washington Street arresting a guy and doing the paperwork when a hot call came out of a knife fight at 1st Street and Jackson, which was close by. Gene told Dick to just leave their prisoner, essentially letting him off the hook, and get going. Dick couldn’t fathom letting this guy walk, especially since the paperwork was now complete. Instead, he put the paperwork in the man’s shirt pocket and told him to stand in the street and flag down the next police paddy wagon he saw. He was then supposed to hand the paperwork over to the officer and have the officer take him to jail. After the knife fight call was over, Dick and Gene learned that the prisoner had done just as he was told and was safely booked into jail, courtesy of Wagon 91.

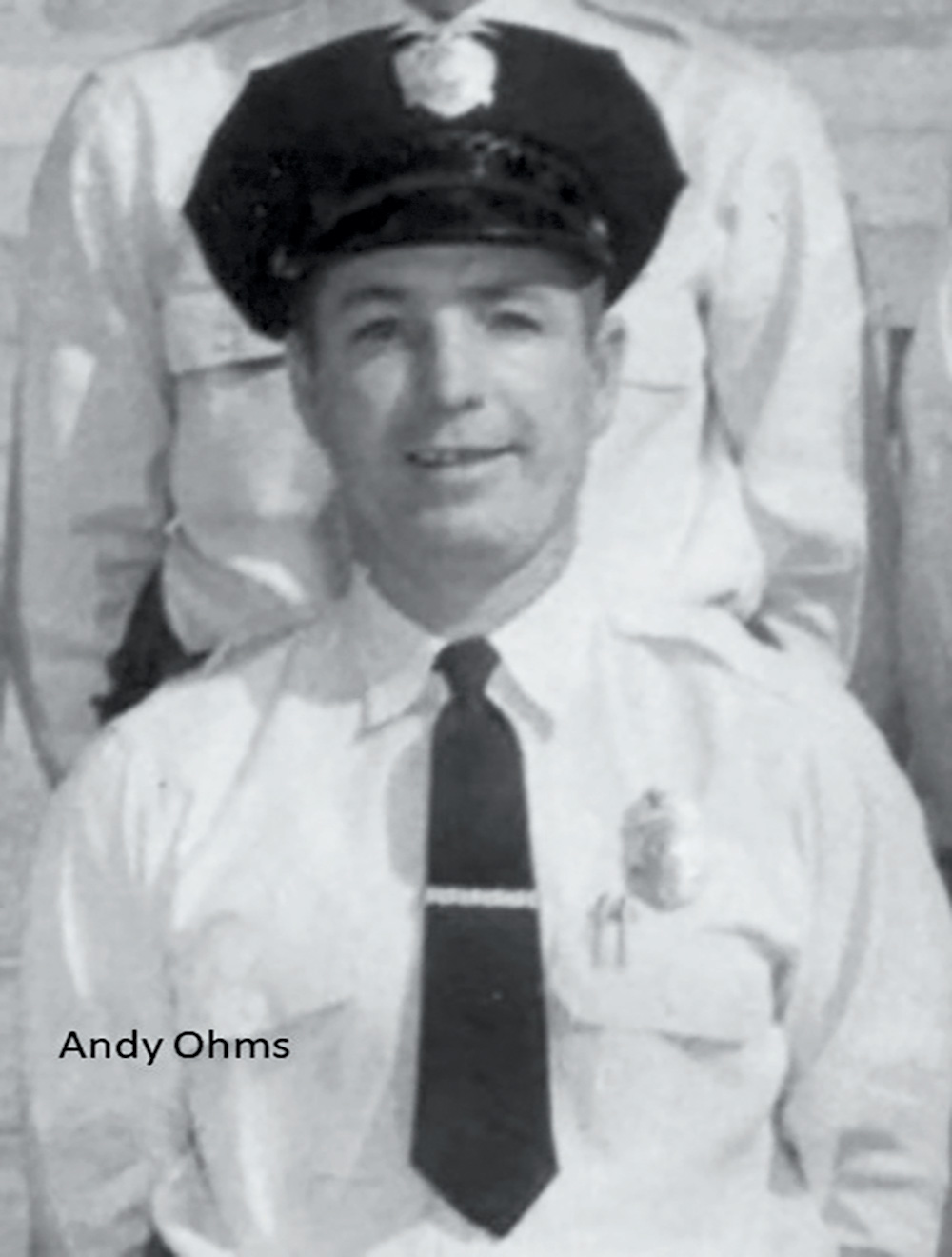

Dead Man’s Bed, As Told to Me by Andy Ohms

Dead Man’s Bed, As Told to Me by Andy OhmsBeat #1 in Downtown Phoenix went from the the Deuce to approximately 16th Street. Most of the time, Andy Ohms’ work would keep him in the Deuce. Because of his prior experience as an officer back east, Andy went solo quickly and it was obvious he knew what he was doing. Andy would work the beat in either a 1948 or ’49 Ford police car or on foot.

If there was something happening at the Orpheum Theatre, Andy would be on foot patrol; if it was slow, he’d be in his car, which had a stick shift and no air conditioning.

One of Andy’s first calls involved a woman who worked at a business in the Deuce. When she arrived for work one evening, she parked her car in the infamous Paris Alley. While parking her car, she managed to accidently run over a “Deuce bum” who was using the asphalt for a mattress. When Andy arrived, he found the car parked on top of the man, who was obviously deceased.

Anyone who worked around Andy knows him for his reputation as the sergeant who cleaned up the jail. But before that ever happened, Andy worked in Paris Alley, which was the busiest area in Beat #1. Most of the calls here involved drunks. There were the occasional shootings, but most arrests were for drunk and disorderly. If a “Deuce bum” was caught with liquor or he was drunk, he would be taken to the city jail. The jail was located at police headquarters at 120 South 2nd Ave., which now houses the Phoenix Police Museum. The jail was sometimes a difficult place to bring a drunk and disorderly prisoner, because of the infamous jail elevator. If your prisoner was a fighter, you would certainly have a problem getting him into and out of the dark elevator. Andy had many a fighter in that elevator, especially when he worked the paddy wagon. After working Beat #1, Andy was assigned to the paddy wagon. Most of the work consisted of finding drunks (usually near liquor stores), throwing them into the paddy wagon and hauling a wagon load to jail.

Andy remembers piling six or seven prisoners into the back of that old paddy wagon. The paperwork to book somebody for drunk and disorderly took about 10 to 15 minutes to complete — just a booking slip, and no report. Andy could squeeze all six or seven prisoners into the elevator at one time. When the doors opened, he thanked God for no riot. Some would have to sit on benches and others on the floor while being processed. Then, the jail guard would put them in a cell. Andy worked the paddy wagon for six to eight months and returned to a beat in the Deuce.

In the late 1970s or early 1980s, “The King of the Deuce” was Sonny Chiago. He was wheelchair bound, always drunk and had a colostomy bag. Sonny was famous (or is it infamous?) for squirting the contents of the bag at anyone who might piss him off, or just for his own sheer pleasure, as he thought it was funny as hell. One hot summer afternoon, Sonny had fallen out of the chair and was lying on the sidewalk in front of Farmers Liquors, between Central and 1st Street on Madison Street. There was almost a full squad of walking beat officers standing around trying to decide how to take care of this without being the victim of Sonny’s bag. Every time one of us neared him — well, you get the picture. After some time, a very well-known lieutenant showed up. This particular lieutenant was known for his spotless uniform, every hair in place, brass polished to a blinding gleam every day and almost always manicured nails.

Anyway, we all knew what was coming. This lieutenant was new to the area and did not know the charming Mr. Chiago. The lieutenant began barking orders about getting Sonny up and out of sight of the citizens. There was some hesitation, and the lieutenant repeated his commands. When a very senior officer began to try and explain things to the lieutenant, he quickly interrupted and repeated his commands. Well, Sonny was drunk. Sonny was always drunk, but he did understand what was going on. Before anyone could say anything (I think we were trying to warn the lieutenant), the squirted stream began to flow all over the shiny corfam shoes and razor-sharp creased lower legs of the lieutenant’s pants! He was absolutely flabbergasted, and for the first and only time I ever saw, he was speechless as well. He got into his car, went southbound on 2nd Street, and I don’t think I ever saw that lieutenant in the Deuce again.

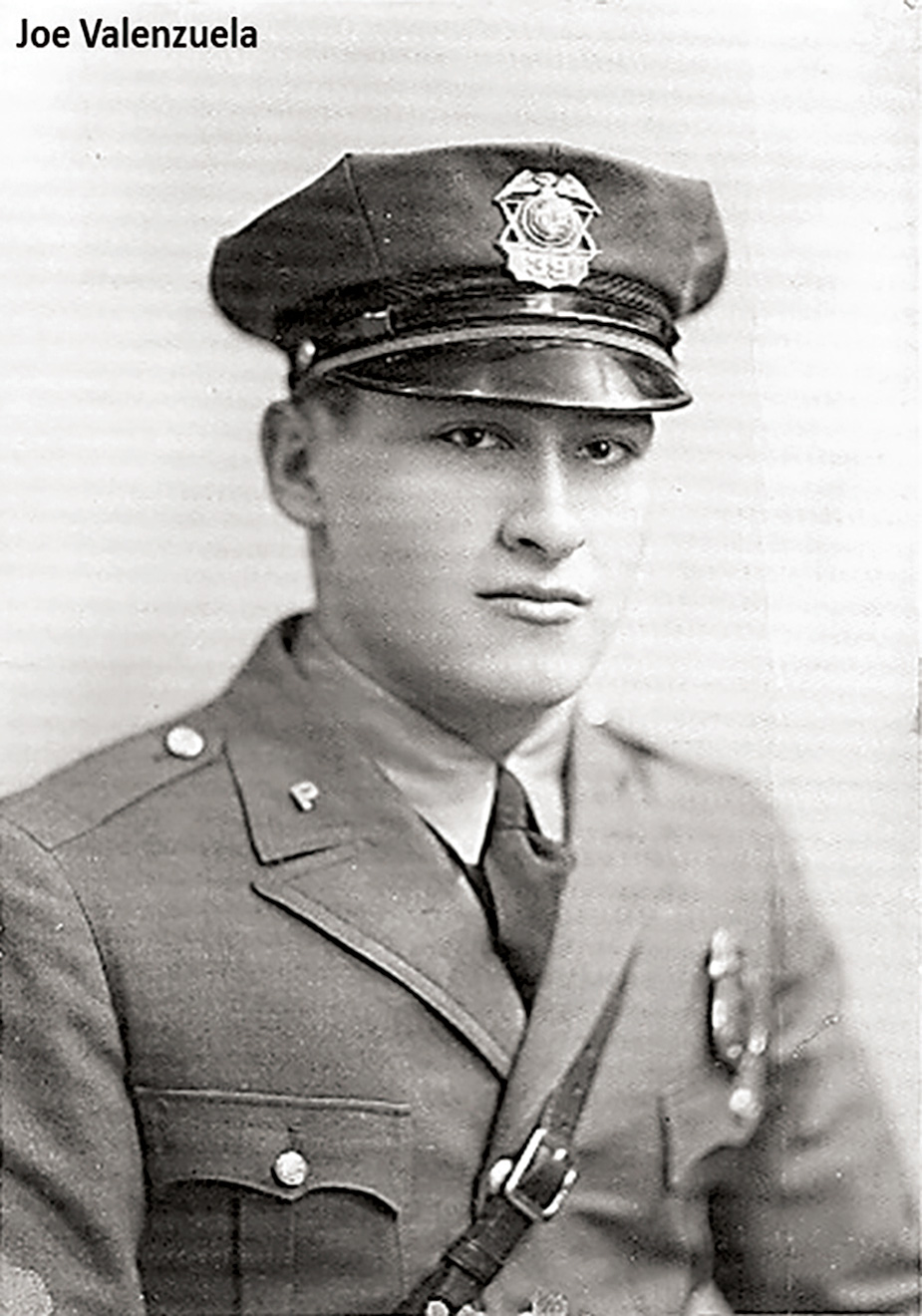

Working the Deuce in 1937, As Told to Me by Joe Valenzuela

Working the Deuce in 1937, As Told to Me by Joe ValenzuelaThere was no police academy back in 1937, so on his first day, Joe Valenzuela was assigned to a training officer. Joe doesn’t remember his very first training officer’s name. He had several, and one of them was John Hicks Sr., who was responsible for making sure Joe learned all the rules and regulations. Joe was pretty sharp #6832 and went solo right away. Back in those early days, new officers were given a uniform and gun and trusted to act properly and work alone without constant oversight from their training officer.

John Hicks went on vacation right after being assigned to Joe, so Joe had to fend for himself for a while and learn by trial and error. While on vacation, John was drinking at a bar in Glendale when he became involved in a fight. John was killed when he was stabbed in the heart with an icepick. Needless to say, John never completed training Joe. Joe went on without John’s leadership and began observing the older, more experienced officers, asking them questions when he didn’t know how to handle particular situations. Joe stayed in patrol for about five or six years. He usually drove a 1934 or 1935 Ford or Studebaker when working his beat. Joe remembers his first police cars had a radio that only received and did not transmit.

Joe worked the downtown walking beat quite often. He would frequently work the area known then as the Deuce or Paris Alley. One day, while driving the paddy wagon, Joe and his partner arrived at 2nd Avenue and Jefferson, just in time to save Officer Ed Langevin, who was being beaten severely by a bad guy. They pulled the man off of Ed and took him into custody after a short struggle. The assailant came out with a few bruises. Joe remembers that he carried a billy club while on patrol and may have used it. Back then, some officers carried brass knuckles or a sap, but Joe did not.

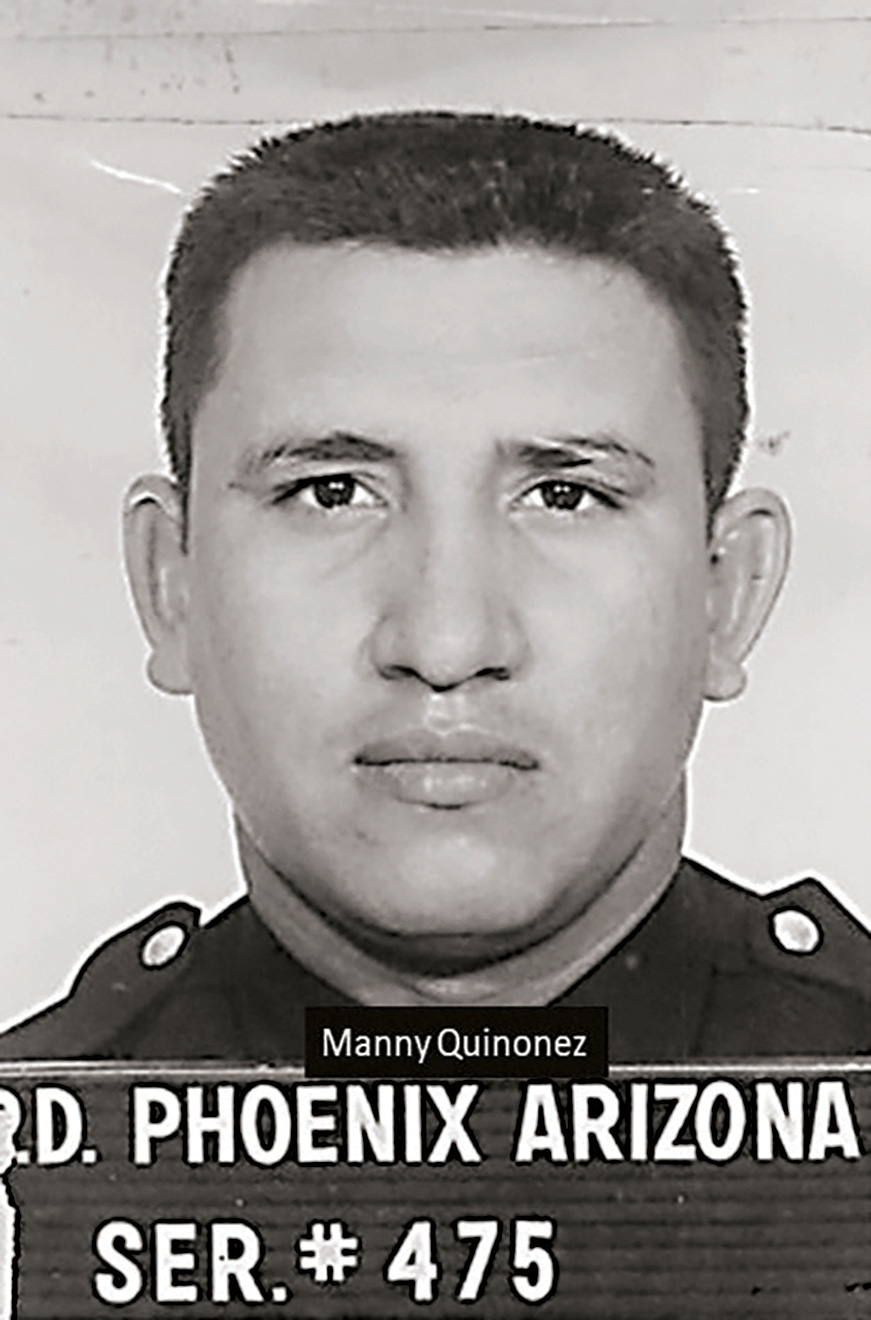

Buy Your Lids in the Deuce, As Told to Me by Manny Quinonez

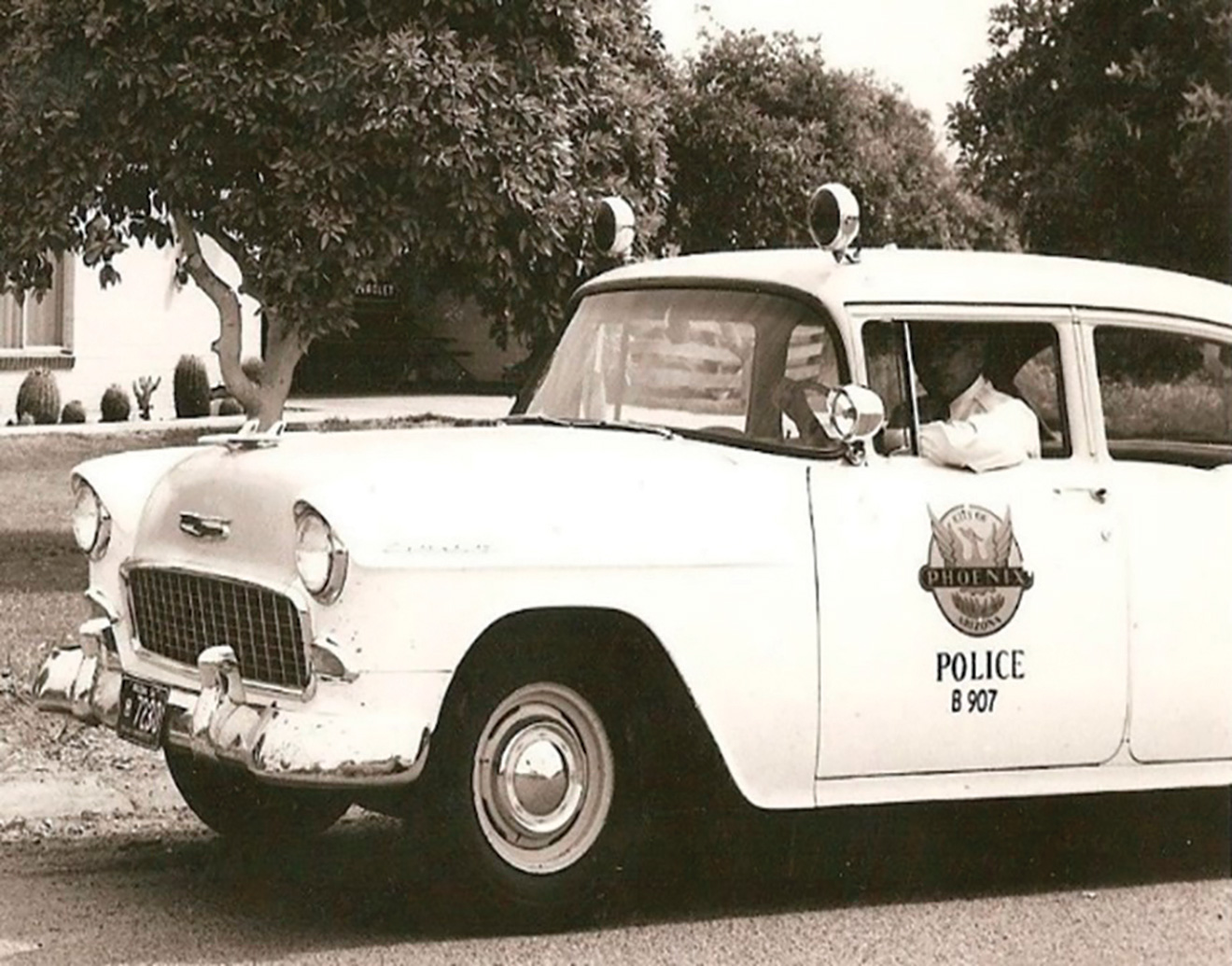

Buy Your Lids in the Deuce, As Told to Me by Manny QuinonezWith Christmas break 1958 over with, rookie Manny Quinonez returned to duty. Now, after just completing his academy training, he had to begin his patrol training. Manny remembers meeting his training officer, Scott Chestnut. Scott was driving his 1955 Chevrolet patrol car. Manny couldn’t wait to drive this beast of a car, but unforeseen circumstances would cause Manny to discontinue his training for an important undercover assignment.

The Department wanted Manny to go undercover in the Deuce and buy marijuana. In 1958, Phoenix was a much smaller town, and it wouldn’t take long for the criminals to meet all the new officers. Manny was chosen for this job because of his anonymity. Manny was using his ethnicity, his youthful appearance and his anonymity to help him go into the Deuce and Paris Alley and start buying marijuana from the dealers operating all over the downtown area.

Manny put away his bright and shiny uniform and put on his old dirty work clothes. His first day at his new job saw him receiving training from veteran narcotics detectives like Earl Irving and Roy Murray on how to buy marijuana. Manny had to learn the language and mannerisms of a drug user. He was told that marijuana was usually purchased in a Prince Albert tobacco tin, also known as a “lid.” A lid of marijuana usually sold for $10. Manny was instructed never to pay more than $10 for a lid.

The Department didn’t have an unmarked car for Manny to drive, so he drove his personal vehicle — a 1954 Ford — to the Deuce and parked it on the east side of Second Street near the La Amapola Bar. Manny didn’t know what to do with his duty weapon, so he hid it under the seat of his car before going into the very sleazy “Mexican only” bar. Manny’s ethnicity and youthful appearance allowed him easy access, and he could see drug dealing as soon as he walked inside. The bar didn’t skip a beat as he walked in, unlike if walking beat officers Fred Green or Lyle Hoffman had walked in; the roaches would scatter and everything would come to a well-rehearsed stop.

Manny knew he would need someone to introduce him to buy marijuana. He approached a very young Hispanic male named Ernesto Miranda. He gave Ernesto the high sign, indicating he wanted to buy some yesca. Ernesto gave Manny the high sign back and then pointed to notorious bad guy Frank Cota. Frank Cota and Manny then went into the restroom, with nobody speaking a word to each other. Frank handed Manny the lid, and Manny gave him the $10. Manny didn’t want to hang around any longer than he needed to; he was somewhat nervous having just made his first undercover buy, so he quickly returned to his car.

Manny knew he would need someone to introduce him to buy marijuana. He approached a very young Hispanic male named Ernesto Miranda. He gave Ernesto the high sign, indicating he wanted to buy some yesca. Ernesto gave Manny the high sign back and then pointed to notorious bad guy Frank Cota. Frank Cota and Manny then went into the restroom, with nobody speaking a word to each other. Frank handed Manny the lid, and Manny gave him the $10. Manny didn’t want to hang around any longer than he needed to; he was somewhat nervous having just made his first undercover buy, so he quickly returned to his car.

Manny moved his car to another area just south and started writing his report as it was still fresh on his mind. Detectives would later show Manny a picture of Frank Cota, whom he quickly identified as the dealer. Three days later, Manny returned to the bar and the same people were inside doing their thing. Manny again gave his high signs and was introduced to Frank Valenzuela. They went into the restroom again, not saying a word, and exchanged Prince Albert for a $10 bill, no problems.

Manny’s short stint undercover only lasted one week. He managed to purchase two lids of marijuana. He made cases on Frank Cota and Frank Valenzuela. Shortly afterward, Officer Andy Ohms arrested both Cota and Valenzuela for a drug-related murder.

(Note: After being paroled in 1976, Ernesto Miranda returned to the La Amapola Bar, where on January 31 he was involved in an argument with another bar patron, who stabbed him to death.)

While still working Beat #1, Manny Quinonez was sent to the Morrison Hotel — which was located on Central Avenue just south of Jefferson Street — on a welfare check call. When he arrived, he contacted the hotel owner, who was quite upset because he couldn’t find the hotel clerk. The cash register was found open and the owner was so scared he didn’t know what to do, so he called the police and stayed by the register. Manny arrived quickly and asked him if he had any empty rooms. The owner replied, “Yes, one room.” Manny was told to go to the end of the hallway and he’d find the empty room.

Manny located the room and cautiously went inside. He peeked inside as he opened the door and could clearly see a male slumped over a folding chair with his hands behind his back. Manny got closer and could see cigarette burns on the man’s face. He was dead and had obviously been tortured. Manny slowly backed away, exiting the room. He secured the scene and used the hotel phone to call police radio. Officer Bill Moore was the dispatcher that particular evening. Manny got Bill on the phone and said, “That call you just sent me on…” “Yeah,” Bill said. Manny continued in a high-pitched squeaking voice, “It’s a murder!” Bill couldn’t understand Manny and asked him, “What’s the matter?” Manny tried to calm himself down, paused, then stated again in a squeaky crackling voice, “Get the homicide people out here!” Homicide Lieutenant Seymore Nealis and Sergeant Gus Oviedo Sr. came out on the call.

One day, Officer Gordon Selby had a brush with World War II Marine/celebrity and Arizona Native American, Ira Hayes. Ira is well remembered for his part in placing the American flag in the ground on Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima.

In the 1950s, Ira Hayes was known to frequent some of the local Phoenix bars and saloons in the Deuce. Ira’s favorite bar was the El Paso Bar. Gordon and Officer Fred Nichols were riding together in the Deuce when they had a run-in with Ira. Ira was not a person they frequently had trouble with, but on this particular day, Ira had been drinking very heavily and, in those days, bartenders did not cut people off like they do now. Ira got out of control, and the bartender called police for help. Gordon and Fred arrived quickly and located Ira. When they learned what was up from the bartender, Ira was taken into custody for drunk and disorderly without any problem.

He was not handcuffed, since he was initially behaving himself. He was taken to the Phoenix police jail, which was located on the top floor of police headquarters. Gordon Selby placed Ira into the very small jail elevator, and the door closed behind them. The elevator was barely lit by a small light for the trip up to the top floor. Upon arrival at the top floor, the light went out and the door opened to the radio room. It was at this time that Ira decided he was going to fight Gordon rather than walk in compliantly. He called Gordon by name and then began Gordon’s very first fist fight in the historic elevator. Gordon said he does not remember what exactly took place other than when the fight was over, both men walked into the jail together.

So, there you have it, just a minor sampling of Phoenix police officer stories about the Deuce and Paris Alley. I save all the stories I’m told and will continue to update my file with more stories in the future. Please keep them coming.