By Ed Reynolds

By Ed Reynolds

Detective (ret.)

Historian, Phoenix Police Museum

The Deuce” was the area from Van Buren Street to Jackson Street, Central Avenue to 7th Street. It consisted of old flophouse hotels, cathouses and businesses like the Busy Bee Café, where many officers went for lunch and dinner. The businesses were mostly old two- and three-story buildings.

The infamous Paris Alley was located between Jefferson Street and Washington Street, approximately in the area of 2nd Street. Paris Alley was shaped like a “T.” Some of the more popular area businesses were Open Door Liquors and Rosita’s Mexican Food. These businesses all had alleys behind them, which were used for backdoor entrances, merchandise loading and unloading, and trash storage. It was not unusual back then for all the downtown alleys to have names, such as “French Alley” and “Gold Alley.” Everyone seems to know Paris Alley because of its location and all the very active businesses in the area.

Paris Alley is where the very last operable Phoenix P.D. call box was located. Call boxes were used for officers to phone headquarters, since early police car radios had one-way communication and could only receive calls. Also, portable police radios didn’t exist yet, so when walking beat officers were needed, a light lit up on police headquarters and signaled officers to call in right away. The key to the call box looked very similar to the current traffic box key. This same call box is now on display at the Phoenix Police Museum.

The Deuce was filled with half a dozen or more old, worn-out flophouses. There were no doors on the rooms, and each room contained about six to eight cots or sometimes just mattresses. The rooms were very inexpensive, and on a weekend, all spaces were taken.

On Friday and Saturday nights during harvest season, buses would bring in field workers to downtown Phoenix. The buses would unload and park on the streets, waiting to carry the laborers back out to the fields and orchards.

The downtown population would increase by the thousands during these weekends. Those arriving on the buses were mostly hardworking and hard-drinking Mexican males. The majority of arrests were for drunk and disorderly (D&D), vagrancy, loitering and disturbing the peace. Any annoying activity would fall into one of these charges. For most of those old-timers, those early experiences would leave some humorous stories to tell. Here’s a few:

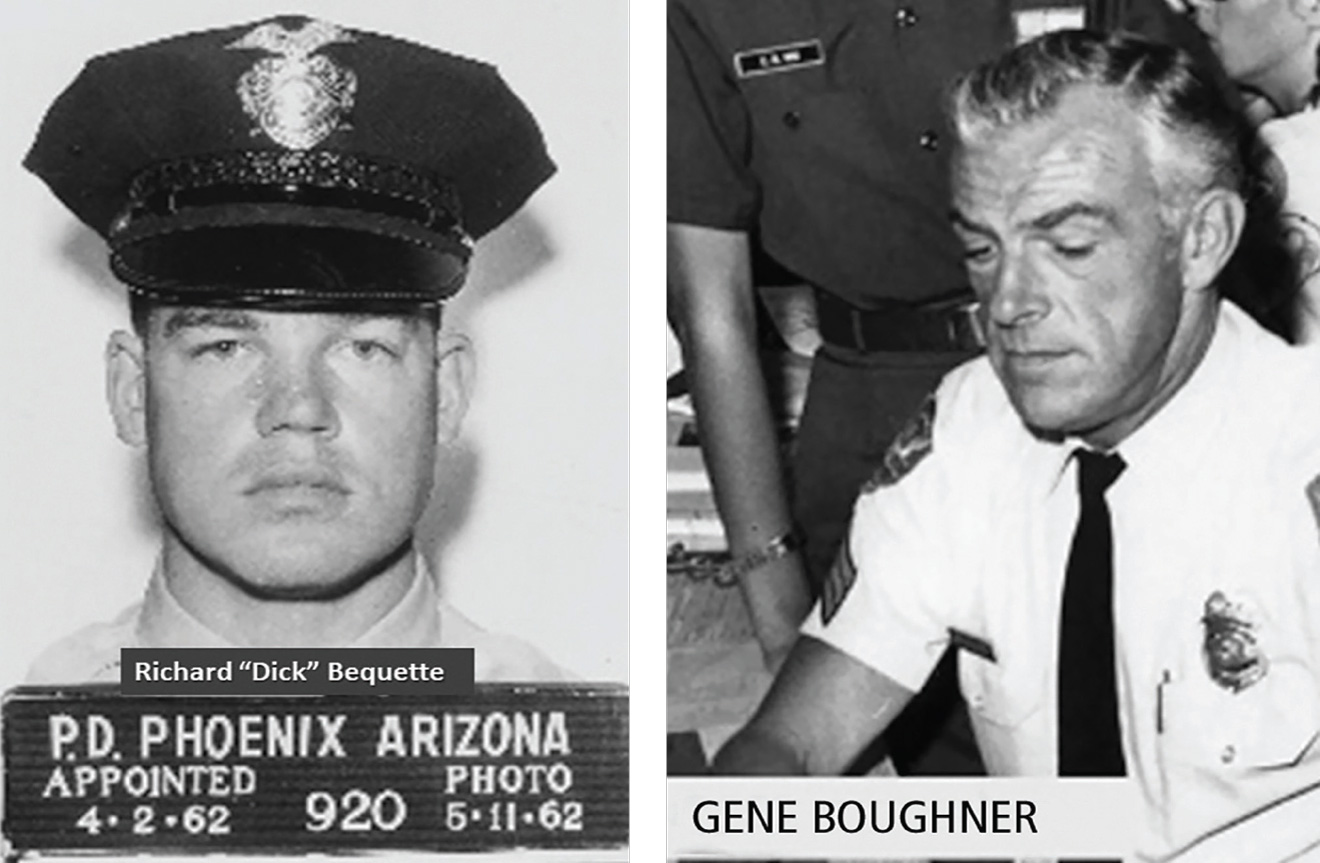

One day, while working in the Deuce, Dick Bequette and Gene Boughner arrested 16 people in the first part of their shift. They put every prisoner inside the paddy wagon, which was built to hold eight to 10 people. After filling the wagon, they drove to the station and backed down the “chute” to get them into the jail. They initially unloaded half of the prisoners and quickly booked them into the jail. This took approximately 30 to 45 minutes to accomplish, and they returned to the wagon, gathered up the other eight prisoners and took them up to the jail to be booked.

Sergeant Gus Oviedo Sr. was the desk sergeant that night. He was quite upset, madly complaining this was too many prisoners to be booking at once.

He definitely did not think it was as funny as Dick and Gene thought it was. Dick and Gene had handled so many filthy, stinking prisoners that night, they insisted on using the untouchable “green soap” to clean up afterward. This soap was an antiseptic hospital soap and quite expensive, but after searching all those prisoners, they wanted to clean up properly. The jail matron agreed and gave them the soap, despite the objections of Sergeant Oviedo. They left the jail and decided to have lunch before hitting the street again. After an enjoyable lunch at the Busy Bee Café, they hit the street and quickly arrested 16 more people and arrived at the chute again, just hours after the previous 16 arrests. Sergeant Oviedo had a conniption fit over their antics. The complaint he wrote up led to a new policy that no more than eight prisoners could be carried in a wagon at one time.

I remember back in the 1980s and early 1990s, an officer could make an arrest, have the booking paperwork done and the prisoner in the wagon in about 30 minutes. After becoming a detective in the l990s and seeing the paperwork increase and the booking procedures go crazy, I would rub it in to young patrolmen about how easy we had it “back in the day.” But never did I ever see anything like what Dick Bequette said he did back in the 1960s. He remembers a night when he and Gene Boughner were on Washington Street arresting a guy and doing the paperwork when a hot call came out of a knife fight at 1st Street and Jackson, which was close by. Gene told Dick to just leave their prisoner, essentially letting him off the hook, and get going. Dick couldn’t fathom letting this guy walk, especially since the paperwork was now complete. Instead, he put the paperwork in the man’s shirt pocket and told him to stand in the street and flag down the next police paddy wagon he saw. He was then supposed to hand the paperwork over to the officer and have the officer take him to jail. After the knife fight call was over, Dick and Gene learned that the prisoner had done just as he was told and was safely booked into jail, courtesy of Wagon 91.

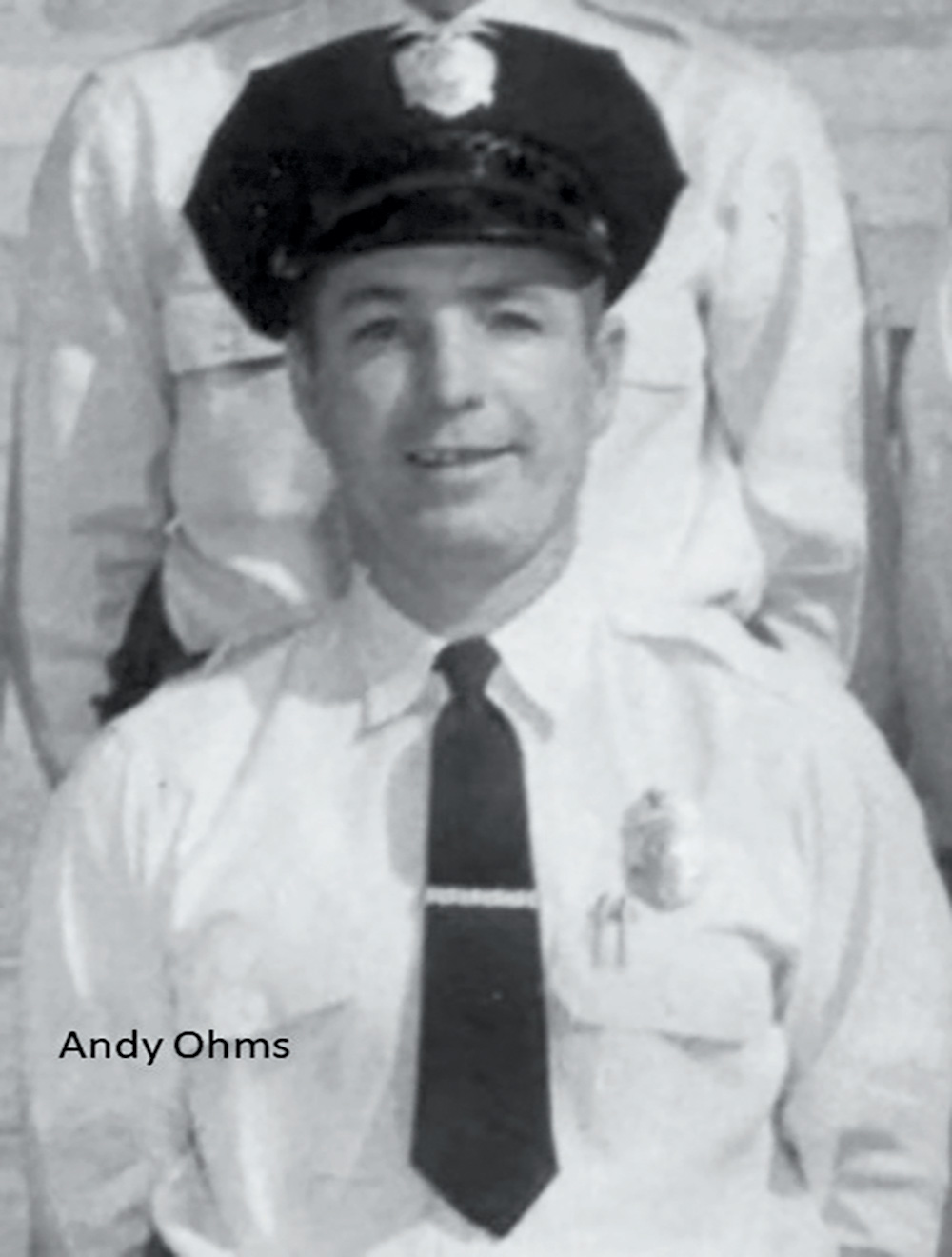

Dead Man’s Bed, As Told to Me by Andy Ohms

Dead Man’s Bed, As Told to Me by Andy OhmsBeat #1 in Downtown Phoenix went from the the Deuce to approximately 16th Street. Most of the time, Andy Ohms’ work would keep him in the Deuce. Because of his prior experience as an officer back east, Andy went solo quickly and it was obvious he knew what he was doing. Andy would work the beat in either a 1948 or ’49 Ford police car or on foot.

If there was something happening at the Orpheum Theatre, Andy would be on foot patrol; if it was slow, he’d be in his car, which had a stick shift and no air conditioning.

One of Andy’s first calls involved a woman who worked at a business in the Deuce. When she arrived for work one evening, she parked her car in the infamous Paris Alley. While parking her car, she managed to accidently run over a “Deuce bum” who was using the asphalt for a mattress. When Andy arrived, he found the car parked on top of the man, who was obviously deceased.

Anyone who worked around Andy knows him for his reputation as the sergeant who cleaned up the jail. But before that ever happened, Andy worked in Paris Alley, which was the busiest area in Beat #1. Most of the calls here involved drunks. There were the occasional shootings, but most arrests were for drunk and disorderly. If a “Deuce bum” was caught with liquor or he was drunk, he would be taken to the city jail. The jail was located at police headquarters at 120 South 2nd Ave., which now houses the Phoenix Police Museum. The jail was sometimes a difficult place to bring a drunk and disorderly prisoner, because of the infamous jail elevator. If your prisoner was a fighter, you would certainly have a problem getting him into and out of the dark elevator. Andy had many a fighter in that elevator, especially when he worked the paddy wagon. After working Beat #1, Andy was assigned to the paddy wagon. Most of the work consisted of finding drunks (usually near liquor stores), throwing them into the paddy wagon and hauling a wagon load to jail.

Andy remembers piling six or seven prisoners into the back of that old paddy wagon. The paperwork to book somebody for drunk and disorderly took about 10 to 15 minutes to complete — just a booking slip, and no report. Andy could squeeze all six or seven prisoners into the elevator at one time. When the doors opened, he thanked God for no riot. Some would have to sit on benches and others on the floor while being processed. Then, the jail guard would put them in a cell. Andy worked the paddy wagon for six to eight months and returned to a beat in the Deuce.

In the late 1970s or early 1980s, “The King of the Deuce” was Sonny Chiago. He was wheelchair bound, always drunk and had a colostomy bag. Sonny was famous (or is it infamous?) for squirting the contents of the bag at anyone who might piss him off, or just for his own sheer pleasure, as he thought it was funny as hell. One hot summer afternoon, Sonny had fallen out of the chair and was lying on the sidewalk in front of Farmers Liquors, between Central and 1st Street on Madison Street. There was almost a full squad of walking beat officers standing around trying to decide how to take care of this without being the victim of Sonny’s bag. Every time one of us neared him — well, you get the picture. After some time, a very well-known lieutenant showed up. This particular lieutenant was known for his spotless uniform, every hair in place, brass polished to a blinding gleam every day and almost always manicured nails.

Anyway, we all knew what was coming. This lieutenant was new to the area and did not know the charming Mr. Chiago. The lieutenant began barking orders about getting Sonny up and out of sight of the citizens. There was some hesitation, and the lieutenant repeated his commands. When a very senior officer began to try and explain things to the lieutenant, he quickly interrupted and repeated his commands. Well, Sonny was drunk. Sonny was always drunk, but he did understand what was going on. Before anyone could say anything (I think we were trying to warn the lieutenant), the squirted stream began to flow all over the shiny corfam shoes and razor-sharp creased lower legs of the lieutenant’s pants! He was absolutely flabbergasted, and for the first and only time I ever saw, he was speechless as well. He got into his car, went southbound on 2nd Street, and I don’t think I ever saw that lieutenant in the Deuce again.

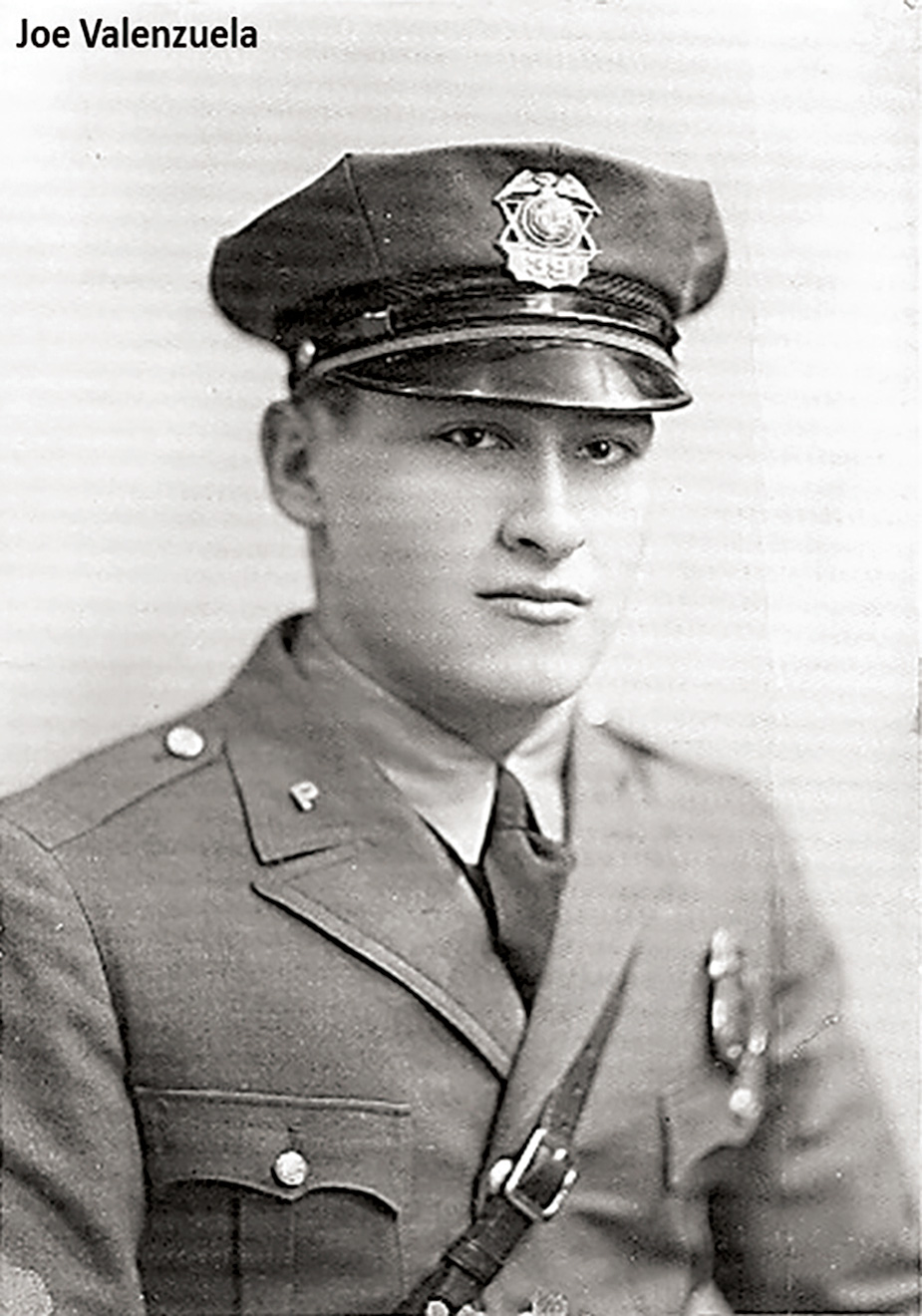

Working the Deuce in 1937, As Told to Me by Joe Valenzuela

Working the Deuce in 1937, As Told to Me by Joe ValenzuelaThere was no police academy back in 1937, so on his first day, Joe Valenzuela was assigned to a training officer. Joe doesn’t remember his very first training officer’s name. He had several, and one of them was John Hicks Sr., who was responsible for making sure Joe learned all the rules and regulations. Joe was pretty sharp #6832 and went solo right away. Back in those early days, new officers were given a uniform and gun and trusted to act properly and work alone without constant oversight from their training officer.

John Hicks went on vacation right after being assigned to Joe, so Joe had to fend for himself for a while and learn by trial and error. While on vacation, John was drinking at a bar in Glendale when he became involved in a fight. John was killed when he was stabbed in the heart with an icepick. Needless to say, John never completed training Joe. Joe went on without John’s leadership and began observing the older, more experienced officers, asking them questions when he didn’t know how to handle particular situations. Joe stayed in patrol for about five or six years. He usually drove a 1934 or 1935 Ford or Studebaker when working his beat. Joe remembers his first police cars had a radio that only received and did not transmit.

Joe worked the downtown walking beat quite often. He would frequently work the area known then as the Deuce or Paris Alley. One day, while driving the paddy wagon, Joe and his partner arrived at 2nd Avenue and Jefferson, just in time to save Officer Ed Langevin, who was being beaten severely by a bad guy. They pulled the man off of Ed and took him into custody after a short struggle. The assailant came out with a few bruises. Joe remembers that he carried a billy club while on patrol and may have used it. Back then, some officers carried brass knuckles or a sap, but Joe did not.

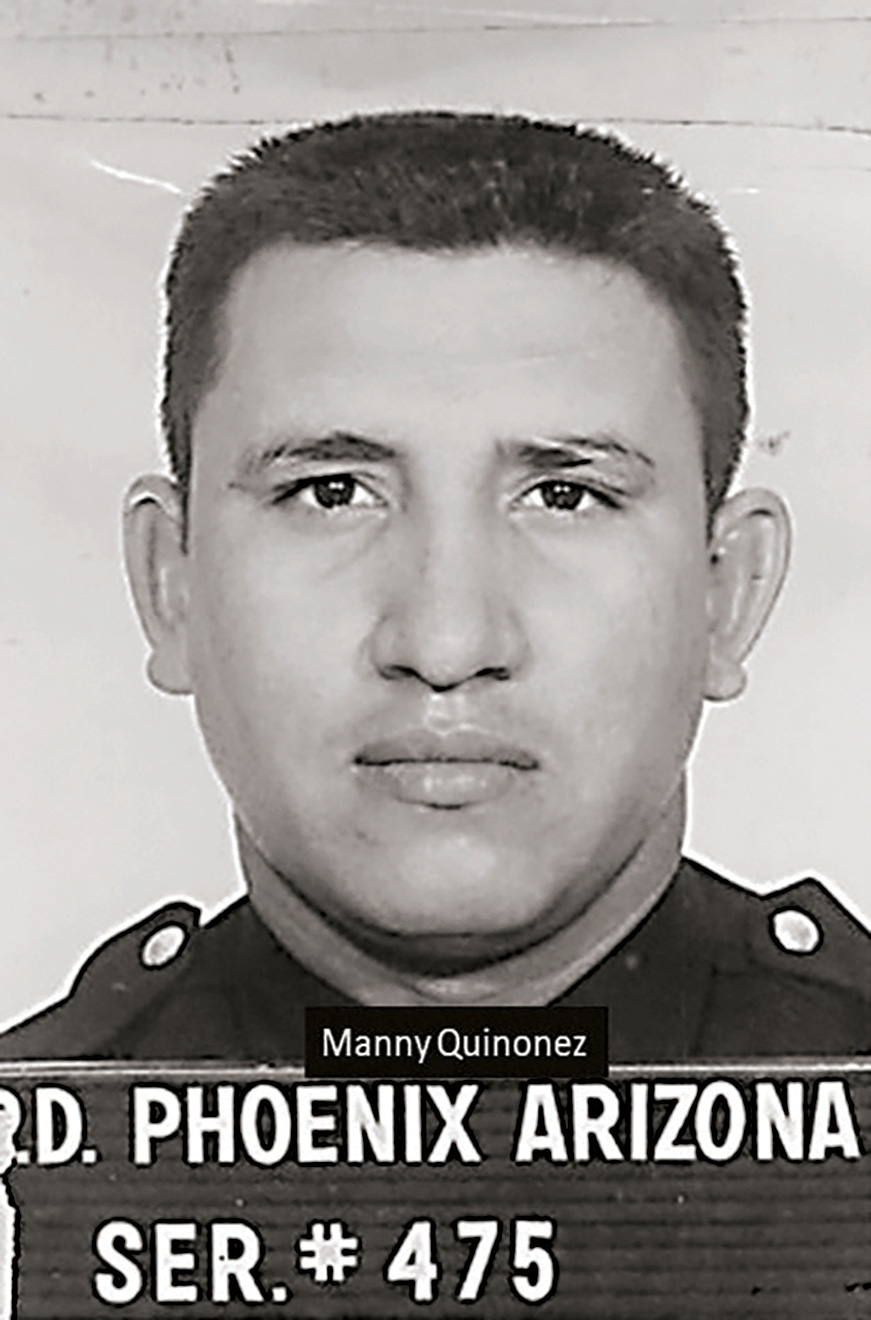

Buy Your Lids in the Deuce, As Told to Me by Manny Quinonez

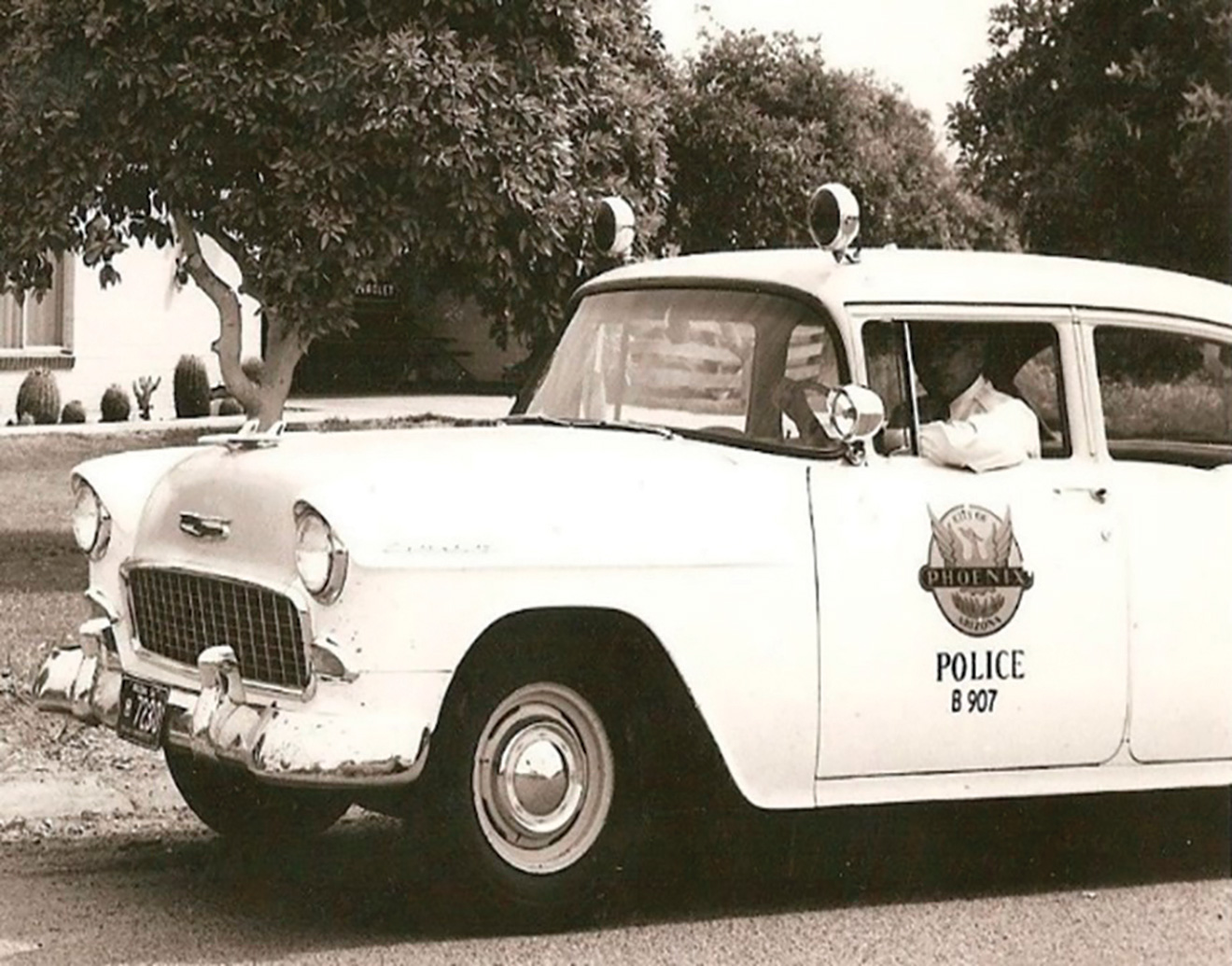

Buy Your Lids in the Deuce, As Told to Me by Manny QuinonezWith Christmas break 1958 over with, rookie Manny Quinonez returned to duty. Now, after just completing his academy training, he had to begin his patrol training. Manny remembers meeting his training officer, Scott Chestnut. Scott was driving his 1955 Chevrolet patrol car. Manny couldn’t wait to drive this beast of a car, but unforeseen circumstances would cause Manny to discontinue his training for an important undercover assignment.

The Department wanted Manny to go undercover in the Deuce and buy marijuana. In 1958, Phoenix was a much smaller town, and it wouldn’t take long for the criminals to meet all the new officers. Manny was chosen for this job because of his anonymity. Manny was using his ethnicity, his youthful appearance and his anonymity to help him go into the Deuce and Paris Alley and start buying marijuana from the dealers operating all over the downtown area.

Manny put away his bright and shiny uniform and put on his old dirty work clothes. His first day at his new job saw him receiving training from veteran narcotics detectives like Earl Irving and Roy Murray on how to buy marijuana. Manny had to learn the language and mannerisms of a drug user. He was told that marijuana was usually purchased in a Prince Albert tobacco tin, also known as a “lid.” A lid of marijuana usually sold for $10. Manny was instructed never to pay more than $10 for a lid.

The Department didn’t have an unmarked car for Manny to drive, so he drove his personal vehicle — a 1954 Ford — to the Deuce and parked it on the east side of Second Street near the La Amapola Bar. Manny didn’t know what to do with his duty weapon, so he hid it under the seat of his car before going into the very sleazy “Mexican only” bar. Manny’s ethnicity and youthful appearance allowed him easy access, and he could see drug dealing as soon as he walked inside. The bar didn’t skip a beat as he walked in, unlike if walking beat officers Fred Green or Lyle Hoffman had walked in; the roaches would scatter and everything would come to a well-rehearsed stop.

Manny knew he would need someone to introduce him to buy marijuana. He approached a very young Hispanic male named Ernesto Miranda. He gave Ernesto the high sign, indicating he wanted to buy some yesca. Ernesto gave Manny the high sign back and then pointed to notorious bad guy Frank Cota. Frank Cota and Manny then went into the restroom, with nobody speaking a word to each other. Frank handed Manny the lid, and Manny gave him the $10. Manny didn’t want to hang around any longer than he needed to; he was somewhat nervous having just made his first undercover buy, so he quickly returned to his car.

Manny knew he would need someone to introduce him to buy marijuana. He approached a very young Hispanic male named Ernesto Miranda. He gave Ernesto the high sign, indicating he wanted to buy some yesca. Ernesto gave Manny the high sign back and then pointed to notorious bad guy Frank Cota. Frank Cota and Manny then went into the restroom, with nobody speaking a word to each other. Frank handed Manny the lid, and Manny gave him the $10. Manny didn’t want to hang around any longer than he needed to; he was somewhat nervous having just made his first undercover buy, so he quickly returned to his car.

Manny moved his car to another area just south and started writing his report as it was still fresh on his mind. Detectives would later show Manny a picture of Frank Cota, whom he quickly identified as the dealer. Three days later, Manny returned to the bar and the same people were inside doing their thing. Manny again gave his high signs and was introduced to Frank Valenzuela. They went into the restroom again, not saying a word, and exchanged Prince Albert for a $10 bill, no problems.

Manny’s short stint undercover only lasted one week. He managed to purchase two lids of marijuana. He made cases on Frank Cota and Frank Valenzuela. Shortly afterward, Officer Andy Ohms arrested both Cota and Valenzuela for a drug-related murder.

(Note: After being paroled in 1976, Ernesto Miranda returned to the La Amapola Bar, where on January 31 he was involved in an argument with another bar patron, who stabbed him to death.)

While still working Beat #1, Manny Quinonez was sent to the Morrison Hotel — which was located on Central Avenue just south of Jefferson Street — on a welfare check call. When he arrived, he contacted the hotel owner, who was quite upset because he couldn’t find the hotel clerk. The cash register was found open and the owner was so scared he didn’t know what to do, so he called the police and stayed by the register. Manny arrived quickly and asked him if he had any empty rooms. The owner replied, “Yes, one room.” Manny was told to go to the end of the hallway and he’d find the empty room.

Manny located the room and cautiously went inside. He peeked inside as he opened the door and could clearly see a male slumped over a folding chair with his hands behind his back. Manny got closer and could see cigarette burns on the man’s face. He was dead and had obviously been tortured. Manny slowly backed away, exiting the room. He secured the scene and used the hotel phone to call police radio. Officer Bill Moore was the dispatcher that particular evening. Manny got Bill on the phone and said, “That call you just sent me on…” “Yeah,” Bill said. Manny continued in a high-pitched squeaking voice, “It’s a murder!” Bill couldn’t understand Manny and asked him, “What’s the matter?” Manny tried to calm himself down, paused, then stated again in a squeaky crackling voice, “Get the homicide people out here!” Homicide Lieutenant Seymore Nealis and Sergeant Gus Oviedo Sr. came out on the call.

One day, Officer Gordon Selby had a brush with World War II Marine/celebrity and Arizona Native American, Ira Hayes. Ira is well remembered for his part in placing the American flag in the ground on Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima.

In the 1950s, Ira Hayes was known to frequent some of the local Phoenix bars and saloons in the Deuce. Ira’s favorite bar was the El Paso Bar. Gordon and Officer Fred Nichols were riding together in the Deuce when they had a run-in with Ira. Ira was not a person they frequently had trouble with, but on this particular day, Ira had been drinking very heavily and, in those days, bartenders did not cut people off like they do now. Ira got out of control, and the bartender called police for help. Gordon and Fred arrived quickly and located Ira. When they learned what was up from the bartender, Ira was taken into custody for drunk and disorderly without any problem.

He was not handcuffed, since he was initially behaving himself. He was taken to the Phoenix police jail, which was located on the top floor of police headquarters. Gordon Selby placed Ira into the very small jail elevator, and the door closed behind them. The elevator was barely lit by a small light for the trip up to the top floor. Upon arrival at the top floor, the light went out and the door opened to the radio room. It was at this time that Ira decided he was going to fight Gordon rather than walk in compliantly. He called Gordon by name and then began Gordon’s very first fist fight in the historic elevator. Gordon said he does not remember what exactly took place other than when the fight was over, both men walked into the jail together.

So, there you have it, just a minor sampling of Phoenix police officer stories about the Deuce and Paris Alley. I save all the stories I’m told and will continue to update my file with more stories in the future. Please keep them coming.

By Josh Champion

Detective (ret.)

As a recent retiree looking back at my career with the Phoenix Police Department, I am proud of the agency I worked for and the good we did. Despite everything I went through physically, mentally and emotionally, I would not trade my experiences for the world.

With morale lagging and headlines dragging our reputation through the mud, this article is for those who know they are doing “20 and a day,” those deciding whether to just pack it up and go, and also those who have to leave because their DROP is ending. The purpose of this is to give you something else to consider as the door to the end of your career nears and then closes.

When our career is done, each of us should be able to say, “I worked in a high-stress, high-volume and high-stakes environment for longer than most would have endured.” We did and we have. Every single one of us has at one point or another worked in patrol or in a specialty detail that has exposed us to some sort of violence or trauma.

Over a decade ago, the Department recognized an “issue” with those of us who lived to be in the moment of what I termed “the blood, guts and gore” of “real” police work. For me, being there at the shooting scenes, the homicides, the serious or fatal collisions, was not so much to see and experience the violence, but to give me the fuel and drive to ensure I could hunt down those responsible for the evil and bring them to justice. Some of us have also been personally involved in critical incidents.

The Department knew this constant exposure could be a problem, but did not know how to label it. They were initially more worried about Department liability if one of these officers “went too far” or “did something that would not pass the headline test.” They did not care about individual officers’ physical or emotional exhaustion, compassion fatigue or burnout. Yet they wanted to find a way to identify these officers so they could be talked to, “disciplined down” or taught to be “less aggressive.”

The system they created was called the Personnel Assessment System (PAS). You were rated on various factors: number of calls to violent scenes, number of arrests, race of the arrested, number of pursuits, “discretionary” arrests or citations issued, etc. For each section of PAS, you had a traffic signal icon showing you your status. If your light in the various areas was green, you were good — keep on keeping on. At yellow, you needed to have a sit-down with your boss and discuss if there were any “issues” with your performance. And at red — look out, you had to meet with your sergeant and lieutenant (with review of your recap, your overtime, your court, your use of leave and discussion of having any off-duty work permits pulled). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I was a “6” car (or hot car) that did not have a specific beat responsibility in my squad area. I earned this role because I was one of the few third-shift, Northside Spanish-speaking officers. I also had training in advanced DUI enforcement and advanced traffic collision courses, was detective qualified, and was a 35mm (non-digital) camera operator. I was live scan/fingerprint trained and had training in biological evidence collection, when at that time, personnel now known as crime scene specialists were usually the only Department employees able to do these tasks. I was one of the first controlled substances officers when the program was started, was in the Department’s first officer-phlebotomist program, and was a drug recognition expert (DRE). Because of my penchant for pursuits, I was told to be on the Pursuit Policy Revision Committee under then-Assistant Chief Michael McCort. Due to my lack of beat responsibilities and my skills, I had earned many yellow and several red lights. Each month, despite the PAS alerts, I was told to keep doing what I was doing. So I did, and I did not realize the emotional and mental damage I was doing to myself along the way.

After a year or two, PAS, for all intents and purposes, went into general disuse. But before it did, I transferred to the old General Investigations Bureau as a detective. I noticed all my traffic lights slowly turned to green, despite the fact that every call I went on was a violent crime. This reinforced to me that this was an attempt for the Department to shield itself civilly from “problem Patrol officers” making a bad decision in a split-second situations. Using 20/20 hindsight, this could have been an early tool to recognize those who needed counseling, assistance or other help.

Sadly, during this time Phoenix rolled along with the national trend of police suicides and not talking about the issues causing them. My first exposure to the dark epidemic was when Brian Bauch, #7022, killed himself. I considered Brian a friend. He had many stressors in his life, but our “police culture” did not allow us to truly talk about it. There was nowhere on the Department to reach out to for help — or if there was, the way to find it was nearly impossible. Over the years, we have had many more officers commit suicide. Most of us on for any amount of time know of at least one or two names, several of us more. Sadly, there are many of us who can name retired officers who also succumbed to the mental injuries suffered on the job.

It wasn’t until about 2012 that I started to quietly seek help through the Department’s “12 free counseling sessions.” I started to see a counselor, as I was having issues coming to terms with being diagnosed with “PTSD symptoms.” To this day, I still struggle with that “label,” which should not be one. After a while, I understood that I should not be ashamed of my mental injuries and started talking to other officers about it. I know at least one other officer who found the courage to start seeking help for themselves after we talked. For them, it just took someone being able to tell them it was OK.

However, it took Craig Tiger, #7356, to shine a bright light on the problem of PTSD and policing in Phoenix. While the Department has made huge strides in the last few years, there are still growing pains in getting us the help we need. I was the first in Phoenix to try to apply for help through the Craig Tiger Act, HB 2502. Once the law was passed, I had to wait for paperwork to be written and approved — which took weeks. (It should be noted that the paperwork issue was well above the pay grade for Sergeant Jared Lowe and the Employee Assistance Unit [EAU] — they were great in getting me help until the paperwork came through!) In the meantime, I decided I was done with my Phoenix career for several reasons. I am one of the retirees who will tell you walking away was the best thing for myself and my family.

However, after I left Phoenix, many of the resources the Department is now offering current employees were no longer available to me. The jobs I have held since I retired have been less hectic and less stressful. The volume of work is considerably less. As another retired co-worker told me, “When we left Phoenix, it was not like we were slowing down; we were hitting a brick wall and are full stop.” But being in a less stressful environment with less volume has allowed more time for intrusive memories, thoughts and feelings to interrupt my daily life. The Tiger Act was a good start; however, that’s all it was — a start. I have left the job, but the mental injuries have not left me. Please, as you head out the door, ensure that you are ready for the transition.

So, for those of you who are approaching the end of your career for whatever reason, make your mental and emotional health part of your equation to stay or go. Make sure you have resources in place for yourself in case you need them. And for everyone reading this, please contact your elected officials and help make mental health treatment for first responders available to those who need it — active and retired. We sacrificed to keep our communities safe; it’s the least we can ask for.

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.), #2949

This year’s Foundation of Retired Police Officers/Dispatchers reunion weekend began on Friday, March 15, with a wonderful tour of our Phoenix Regional Police Academy. Organized by Advanced Training Bureau Sergeant Johnathon Dennison, this was a real hit with the attendees. Families with children and grandchildren took part in demonstrations in the tactical village, shooting scenarios and the Taser. We all received just a glimpse of the thorough training received by our Phoenix Police recruits. For many of us, just walking the Academy grounds brought back memories of how it was “back when” and admiration for our active officers and our Department, which supplies the very best in training.

Later that evening, choir practice was held at Helio Basin Brewing, 3935 E. Thomas Rd. About 70 folks met to enjoy great drinks, food and company. This is a tradition that started last year for our reunion weekend, and it was so well received we knew we needed to do it again.

Our Foundation/Museum picnic was held on a beautiful Phoenix spring day. Once again, great musical entertainment was provided by Bill Lewis’ Borderland Band. Their music is fantastic and so are they! They donate their services and their talent to make our picnic something really special. You guys rock!

Thank you to the Special Assignments Unit (SAU) for bringing your equipment displays, weapons and presentations to the crowds. That really wowed a lot of folks.

We had 311 signed-in attendees and there were uniformed Phoenix Police officers who did not sign in, so our total attendance was approximately 340.

Our officer attendees ranged from highest serial number #10614 — belonging to Gage Quintana, Karla Clark’s grandson, who just graduated from our Academy on March 21 — to our own legend Ken Renter, #387.

This year, our Foundation picnic honored 26 retired dispatchers. The Phoenix Police Museum provided beautiful custom-etched glasses to award the folks who used to tell us where to go, but also who always had our backs. Thank you to all our retired and current dispatchers. You are important!

I would like to extend a special thank-you to all who support the reunion picnic, and to those who show up very early to set up and stay very late to tear down. You are very special people and it could not happen without your help and support. I love all of you. See ya next year!

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.), #2949

Bobby Chavez is a warrior. He is a man of integrity and principals who is loved by all who have had the privilege of working with him. Bobby was born in El Paso, Texas, but moved to Phoenix as an infant. At age 17, when the Vietnam War was at its height, Bobby wanted to join the war effort and enlist in the United States Marine Corps. But his young age required his parents to sign the enlistment papers. His dad initially refused, but Bobby patiently explained (as he would do many times later in his life to those he wrote traffic tickets for) that he would find a man on the street to pose as his dad and sign the papers. His dad relented and signed. Bobby went straight from boot camp to Vietnam and served honorably until 1970.

In 1972, Bobby married the love of his life, Esther, and they had two sons, Ben and Adam. (They now also have three grandsons and one granddaughter.) For a while, Bobby worked as an inhalation therapist, but from the age of 12, he had wanted to be a police officer. With hope of fulfilling his dream, he applied to the Phoenix Police. Unfortunately, he did not meet the height requirements the Department had at that time, so he and his young family moved to California for a job opportunity. Not long after settling in California, Bobby received a letter from the Phoenix Police offering him to enter the hiring process. He returned to Phoenix to chase his longtime dream. In 1974, his dream came true, and Officer Robert Chavez, #2744, began his career as one of Phoenix’s finest.

In 1999, after serving the citizens of Phoenix for 25 years, Bobby retired from the Phoenix Police. He became ill with symptoms that were difficult to diagnose and resulted in many trips to different specialists over years for various tests. In some cases, Bobby had to be treated by doctors “out of network,” which created a huge financial burden on the Chavez family. In July 2015, Bobby was diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration (CBD), a very rare brain disease that worldwide affects only about 3,000 people. The condition is terminal, as the disease causes the brain to degenerate slowly. Watching Esther care for her terminally ill husband with such devotion and love has served as an inspiration to all who have visited the Chavez family over the years. Esther’s road is not an easy one, but she is sustained by her great faith and love.

In July 2018, I was contacted by retired Officer Jerry Funk, #2590, a friend and past PPD partner of Bobby’s. Jerry told me about Bobby and Esther and asked if the Foundation of Retired Police Officers could be of assistance. After speaking with Jerry and meeting with Esther, it was determined that every available dollar that the Chavez family had went to Bobby’s medical care. As a result, much-needed home repairs had been put on the back burner; the family home fell into a state disrepair with peeling paint, wood rot from leaks and more. Esther was very concerned about how she was ever going to pay to have the house brought back to standard. Michael Abbate, owner of Crafted Remodeling and a board member for the Foundation, met with Esther and, in a matter of hours, determined what work needed to be done to the house.

With the Foundation paying for materials and Crafted Remodeling donating labor, it was time to fundraise for the home repairs.

Thanks to the support of many fellow retired Phoenix police officers and dispatchers and PLEA Charities, the Foundation was able to raise enough money for the home repairs and presented Esther with a check to help with expenses.

Many retired officers, dispatchers and a few current Phoenix police officers arrived on a very hot August day to landscape the front yard with new rocks. The Chavez’s large front yard occupies a corner lot. Wow! These folks worked hard spreading ton after ton of rock and had fun while doing it. However, I was told to never again schedule a yard remodel in August. I will heed that advice.

Esther wanted to make sure that I mentioned how very much she and Bobby appreciate the Foundation of Retired Police Officers, PLEA Charities and all the old and many new friends who have been such a wonderful help.

By Edward Reynolds

Detective (ret.)

Historian, Phoenix Police Museum

I was recently asked to write a story about Phoenix Police motorcycle officers. I immediately began to put together background information and stories I’d gathered from the Association of Retired Phoenix Officers, its website and some old internet articles about Indian and Harley-Davidson police motorcycles. This is when I discovered a mystery that definitely needs solving. Let me explain.

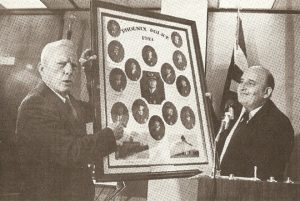

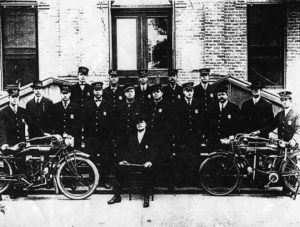

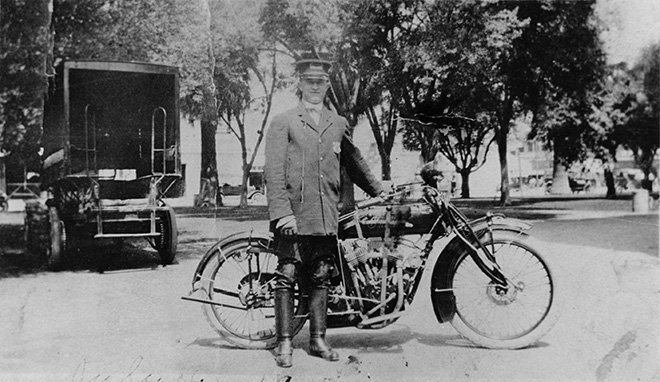

While spending endless hours scanning photos last year at the Phoenix Police Museum, I came across several 1973 photos of former Chief of Police Larry Wetzel recognizing Harrison M. Williams as being the very first Phoenix Police motorcycle officer. In 1973, Williams was 80 years old when he told his story to an Arizona Republic reporter. He said he joined the Phoenix Police Department in 1911, when he was only 18, but had lied about his age, saying he was 21, or at least everyone assumed he was 21. That was the minimum age required to be a police officer then. While other officers were walking, riding bicycles or horse-drawn carriages, Williams patrolled the streets on his M&M belt-driven cycle, he said.

Phoenix Police Chief A.J. Moore had invited Williams to join the Department and bring his cycle with him, the article continued. Williams was issued a standard .45 caliber Colt revolver, and with no training whatsoever, was put to work for $100 a month, a healthy salary back in those rough days. The downtown area had a saloon in every other building, Williams described, but downtown Phoenix was surrounded by farmland and dairies.

He would have to ride cautiously on the sometimes very muddy streets because the roads weren’t paved at the time, he said. Williams used to tell his grandchildren a somewhat “tall tale” about how one day he was walking down the board-covered walkway on a rainy day and reached down to pick up a man’s Stetson hat. He was surprised to see a man’s head underneath the hat, and below that the man’s body and his horse still under him.

Around 1914 or 1915, the new County Sheriff offered Williams a $25-a-month raise to lateral over, which he quickly did. Given his choice of a new motorcycle, Williams chose a chain-driven Indian cycle, which he ended up driving all over the state of Arizona as a deputy sheriff.

Like everyone else who read this 1973 article, I had no problem believing that Williams had to be the first Phoenix motorcycle officer. But as I continued my research, Kathy Bell at the Phoenix Police Museum located an article, “Who Was the First Phoenix Motor Officer?” written by Kenneth Arline for a Phoenix Police newsletter. It identified Jerry “Missouri” Thompson as the first Phoenix motorcycle officer. According to Arline’s research, “Missouri” Thompson was hired in 1910 to enforce Phoenix’s new Ordinance Number 406, which limited speed on all downtown city streets to 10 mph and 12 mph elsewhere. A couple of days before enforcement began, Phoenix newspapers advised residents that enforcement of Ordinance 406 would begin soon:

“The motorcycle cop will follow after automobiles and watch the speedometer on the cycle. When he finds the indicator creeping up to 15 or 20 mph he will shoot ahead and stop the car, take the names of the occupants and politely ask them to appear at the police station at the earliest possible time.”

The first ticket for speeding in an automobile was issued to Frank Viault and Marcus May and the first ticket for speeding on a motorcycle went to a young man named Spencer, Arline wrote. They each paid their $15 fines.

S.J. Tribolet of Tribolet’s Cold Storage was the first to fight a speeding ticket in court, according to Arline. Officer Thompson testified before Judge Frank Thomas that he was 10 feet behind Tribolet when he clocked him doing 20 mph on Second Street, from Taylor to Monroe Street in downtown Phoenix. Officer Thompson also testified that when Tribolet slowed down at Monroe, he passed a hay wagon and caused a bicyclist to jump off his bicycle to avoid being struck by the car. Tribolet denied he was speeding and accused the officer of inexperience in “catchin’ fellers.” Judge Thomas found Tribolet guilty and fined him $15.

One of the first to beat a speeding ticket, Arline wrote, was Louis Sands of Glendale. He admitted doing 18 mph on Grand Avenue, on his way to an emergency at his farm, where an employee had died. Mr. M.W. King was the first person to go to jail in lieu of paying the $15 fine for speeding.

Speeding in the downtown area apparently was a big issue because the newspaper frequently reported merchants’ and pedestrians’ complaints about the 10-mph speed limit, which nearly every delivery wagon in town seemed to violate.

I have also located newspaper articles written about Officer Nick Papo, who is identified by his family as having been the first Phoenix motor officer. I am told a 1914 photograph shows Papo on a Phoenix Police motorcycle. I haven’t found that one yet, although his obituary in the newspaper also identified him as being the first. More research needs to be done on Papo.

However, I also came upon other old photos of Phoenix Police Department officers and motorcycle officers.

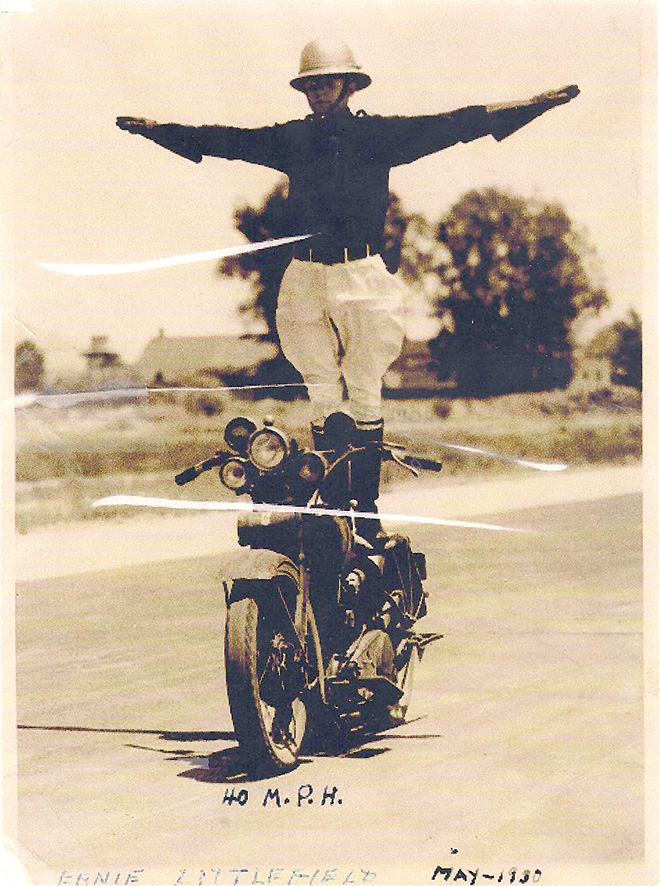

So, the mystery remains. What else might I find? Will the real first Phoenix Police motor officer please stand? I’m betting on good ol’ “Missouri” Thompson, but who knows what else might be out there that I haven’t stumbled upon yet? As I search through the thousands of photos in the Phoenix Police Museum files, not a day goes by that something interesting doesn’t pop out at me. I will continue this story as I move along through “motor” history. I just finished scanning all the photos on file for Phoenix’s “Most Famous Motor,” Ernie Littlefield. Or was he the most famous? The Museum has a photo of Littlefield standing on his motorcycle with his arms outstretched. But I remember Glenn Martin, a 1940s and ’50s motor, telling me he had done a handstand on the handlebars of his bike while driving the city’s streets. More on that in future articles. I can’t wait for the stories that await me. If you have any stories or information, please email them to me at ereynolds5@cox.net and I will consider them for future chapters on the “History of Phoenix Police Motors.”

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.)

The 2018 Reunion Picnic, hosted by the Foundation of Retired Police Officers, was the biggest and best picnic of the past five years. This was a three-day event, beginning Friday, March 9, with a tour of the Phoenix Regional Police Academy.

For most of the 100 retirees who attended, this was the first time they had returned to the Academy in more than 20 years. Seeing the beautiful, modern campus and learning about new training techniques brought memories, awe and pride for how far we have come from our days as police recruits. Thank-you to Sergeant Sonny Hudson and the training staff for putting on such a great program. Retirees asked whether the program would return next year, and Sergeant Hudson, as we were leaving, did say that he hoped to see us again next year. I hope so, too! After three hours at the Academy, many retirees headed out to the Dubina Brewing Co., at 17035 N. 67th Ave., #6, in Glendale, for refreshments. Retiree Jan Dubina always has great “blue light” specials.

The picnic was held March 10 at South Mountain Park, and it was a wonderful location. Most attendees approached me and expressed their hope that we continue having the picnic there. I’d like to thank retired Commander Robert Demlong and retired Lieutenant Stan Hoover for arranging this venue. We had our own private, secure area with a huge parking lot, and thanks to Chuck Boyd, we had a great hot dog cart and Mexican food truck. The Borderland Band, with our own retired Commander Bill Louis and retired Sergeant Michael “Mic” Sheahan, was outstanding. They really are talented and added so much enjoyment to the picnic. SAU had several of their specialized vehicles there for our grandchildren’s enjoyment, and retired Lieutenant Mike Nikolin brought two antique police cars from the Phoenix Police Museum.

The picnic was held March 10 at South Mountain Park, and it was a wonderful location. Most attendees approached me and expressed their hope that we continue having the picnic there. I’d like to thank retired Commander Robert Demlong and retired Lieutenant Stan Hoover for arranging this venue. We had our own private, secure area with a huge parking lot, and thanks to Chuck Boyd, we had a great hot dog cart and Mexican food truck. The Borderland Band, with our own retired Commander Bill Louis and retired Sergeant Michael “Mic” Sheahan, was outstanding. They really are talented and added so much enjoyment to the picnic. SAU had several of their specialized vehicles there for our grandchildren’s enjoyment, and retired Lieutenant Mike Nikolin brought two antique police cars from the Phoenix Police Museum.

The highlight of the picnic, aside from seeing old friends and winning prizes, was a special ceremony to honor our officers with three-digit serial numbers who attended. The Police Officers Memorial pin was presented by Chief Jeri Williams to each of our 21 three-digit honorees. Two weeks before the picnic, I was missing friends, fellow retirees, who had supported me in starting the Facebook group and our first picnic: Walt Smith, #659, and Tom Kosin, #1528, were the wind beneath my wings and my motivation. It was too late for Walt or Tom to receive recognition for their service to our Department, but thinking of them was what prompted this ceremony. Thank-you, Chief Williams, for making this very special. Our honorees are:

- Sam Howe, #375

- Ken Renter, #387

- Carrol Cooley, #413

- Ed Kiyler, #435

- Manuel Quinonez, #475

- Richard Twitchell, #513

- Benny Barber, #582

-

The Borderland Band: Jesse Zamora, Gary Sachs, Mike Sheahan and Bill Louis Howard Goldman, #677

- Ben Bacchi, #684

- Frank Albright, #734

- Gene Boughner, #773

- Jim Humphrey, #783

- Jerry Statham, #844

- John Burk, #849

- Dick Swayzee, #882

- Dudley Gibson, #942

- Bill Goodman, #943

- Len Zingg, #954

- Dick White, #990

- Margaret Cassidy on behalf of Edward Cassidy, #307, and Ralph Dixon, #917

God bless you all.

I would like to acknowledge and thank Carol Campbell, who chaired the merchandise raffle, and Steve and Martha Proctor, who have chaired the gun raffle for the past five years.

The amount of money raised and donated to our Phoenix Police Museum this year totaled $10,934:

- $3,075 from the merchandise raffle

- $5,775 from the gun raffle

- $1,120 from sales at the Museum table

- $964 from the Museum open house

Thank-you to Ed Catlett and his sign-in crew, who were swamped at times and had to open up a second table to sign in attendees. And thanks to all of you who worked hard selling raffle tickets, working the raffle table, setting up tents and breaking things down at the end of the day. It took a lot of helpers and you all really came through.

William Wood won the Dave Lane custom-built pistol this year, a stainless-steel Caspian .45 with candy apple blue and gold-plated parts, valued at $5,000. James Morrison won the Remington 870 Police Magnum shotgun donated by Sheahan, valued at $600.

Congratulations to all merchandise and gun raffle winners.

Did everyone notice the Phoenix Police Cadets at the picnic?

I had never seen these young people, formerly known as Police Explorers, prior to this event and I was totally impressed with their #9771 performance and actions. They directed traffic into our venue, helped put up tents and were so well organized, polite and professional. They were there to pitch in and help, and did they ever. Nine cadets were present and each of them will make fantastic Phoenix police officers one day. Thank-you, Officer Dave Barrios, for leading this commendable group of young adults.

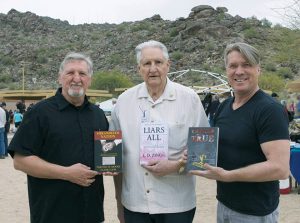

Another first for this year was our “Authors Table,” featuring former Phoenix police officers who have written outstanding books. This year we had retired Sergeant Darren Burch with Twisted but True, retired Lieutenant Len Zingg with Liars All and retired Detective Tim Moore with Mirandized Nation. All authors donated a portion of their proceeds to a police charity. Gentlemen, thank-you for participating, and I was glad to see your sales far exceeded your expectations.

Thank-you to South Mountain Precinct Commander Jim Gallagher, who, along with some of his precinct troops, attended in uniform and enjoyed hearing stories of patrolling Phoenix back in the “olden” days.

Day 3 of our reunion weekend was an open house at the Phoenix Police Museum. This was very well attended. It was so entertaining to watch the young grandchildren and great-grandchildren trying on the police shirts and sitting in the police car. The Museum staff are all volunteers and we appreciate their opening the doors on a Sunday. It was a great three days and everyone attending any or all of the events enjoyed themselves immensely.

I have enjoyed creating and administering the Officer/Dispatcher Facebook group, followed by the picnic a few months later. I could not have organized the picnic for the past five years without a lot of friends who believed in me and the goals of making retired life a little better for Phoenix police retirees — friends who worked very hard to help get it all started.

Thank-you, Chuck Boyd, Fran Anatra Garcia, Carol Campbell, Margaret Cassidy, Al Contreras, Ruthie Cooper, Ronnie Hawthorne, Nan and Cave Golding, Stan Hoover, Dave Lane, Cleo Lewis, Peg and Lou Martinez, Franklin Marino, Dale Norris, Steve and Martha Proctor, Becky Rice, Connie “CJ” Tyler, Sara and Bob Van Houten, Dick White and all of you who have donated raffle items and worked so hard to sell tickets, put up tents and give of yourselves to help fellow Phoenix police officers. Thank-you, all!

To view more photos from the 2018 Phoenix Police/Dispatcher Reunion Picnic, please visit our Foundation of Retired Police Officers website at www.FORPO.com.