By Joyce Hubler

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.)

In early February, Chuck Roseberry contacted me and told me a story. Amy Ugalde, wife of Sergeant John Ugalde Jr. (who recently passed from cancer), and their young daughter were visiting John’s grave. The young daughter saw a particular headstone that she said she would like for her Daddy’s grave and a bench that she would like for the gravesite to sit on when visiting. Amy had been hit with many unforeseen expenses, and this was not in the budget. Chuck asked me if the Retired (and almost retired) Phoenix Officers/Dispatchers group could help. There was no doubt in my mind that we could help. Chuck posted the following:

“Donation Account for John Ugalde Jr.: Most of you are aware of the recent passing of Motor Sergeant John Ugalde Jr. following a brief, courageous fight with cancer. His dad, John (Gator) Ugalde, is a member of our retirees group. John’s young daughter likes to visit her Dad’s final resting place and would like to have a nice headstone with a PPD badge and maybe a bench. I would like to see our group cover this cost and maybe a little extra to help Amy (John’s wife) with other expenses, as any other help is limited in a non-line-of-duty death.”

In just over a week, the generosity of our Retired Officers/Dispatchers had raised $5,375. Again, thanks to all of you for pulling together for an important purpose. We may be a grassroots, informal group, but we do have heart.

Chuck Roseberry presented the check to Amy Ugalde on March 3 and wrote the following:

“Last night I had the pleasure of joining Amy Ugalde, widow of Sgt. John Ugalde Jr., and several other friends for dinner on her 40th birthday. After dinner I presented her with two checks from this great group of retirees totaling $5,300!!! This money will be used to help cover the $7,300 cost of a nice headstone and a bench at the gravesite. Amy was very, very grateful and wanted to make sure I thanked each and every donor. She kept repeating, thank you, thank you, thank you. Since I’m unable to thank each of you personally, know that Amy was very touched by your generosity. Remember the account is still open, and I will repost instructions and account numbers. Once again, for Amy and especially for Brynn, who misses her Dad constantly, thanks to a generous, great group. An account has been opened at Arizona Federal Credit Union and donations can be made at any branch to the following account: DONATION FOR JOHN UGALDE JR., Account 10028048.”

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.)

On March 12, we had our third annual picnic hosted by the Retired Phoenix Police Officers/Dispatchers for the purpose of reconnecting, having a great time and supporting our Phoenix Police Museum.

At the first picnic held in 2014, 225 folks showed up. This was astounding because I only expected that, at the most, maybe 60 to 80 people would show up for a first-time event. The second year approximately 280 people showed up, and this year we had an amazing 295 retired and current Phoenix police officers, dispatchers and family members in attendance.

The raffle was stupendous, with donations of a beautiful blue fox fur coat; airplane rides; glider rides; massages; gift certificates for restaurants, casinos, movies and baseball games; and a new leather motorcycle jacket. We also had artwork sent by retired officers, books authored by retired officers, and wonderful selections of wines, whiskeys and tequilas. Thank you to everyone who donated!

Of course, a huge hit was the one-of-a-kind commemorative M1911 pistol donated by our own very generous David Lane. This particular M1911 was designed by Dave and built by Frank Glenn. Frank is a retired DPS armorer. Steve Proctor donated a Ruger 10/22 rifle.

Chief Joe Yahner attended and greeted some of our retirees with three-digit serial numbers, many of whom came from out of town to attend the picnic. We had attendees from Missouri, Arkansas, California, Texas and from all points in Arizona.

As an added treat, on Sunday, March 13, the day after the picnic, Rob Demlong opened the Phoenix Police Museum for a special retired-officers-only open house. This was greatly appreciated, especially by the many retirees who attended from out of state.

All totaled, $11,755.55 was raised and donated to our legacy, the Phoenix Police Museum. Please keep in mind that the Retired Phoenix Police Officers/Dispatchers Facebook group is not affiliated with the Association of Retired Phoenix Officers (ARPO), PLEA, Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) or any similar organization. Because there are no affiliations, we have no membership dues, no elections, no meetings, etc. All we have is a love for one another and a willingness to help our fellow retirees, which makes it even more amazing.

The retired officers, dispatchers and spouses who worked so very hard on making this a huge success are as follows.

Raffle Committee: Chairs Sara and Bob VanHouten and members Karla Clark, Toni Brown, Peggy Mecham Milsap, Eunice Scott, Nan and Cave Golding, and Lou and Peg Martinez. The committee came out early on the morning of the picnic #4567 to help set up. Thanks to all of you and those who donated items for a great cause.

Gun Raffle Committee: Martha and Steve Proctor. Martha also designed and made our picnic flyer and the tickets for the gun raffle.

Sign-In Committee: Chairs Ed and Kim Catlett, assisted by Duffy and Bob Cropper, Lisa Constien Schultz, Ruthie Cooper, Dudley Gibson, Bob Grinslade and Deneen Price.

We look forward to seeing you at next year’s event and will keep you posted as we plan things out.

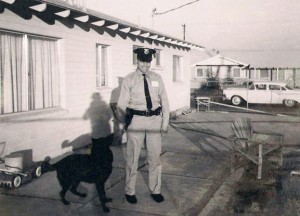

I was raised in Denver, Colorado, and I had wanted to be a police detective for years. I turned 22 in 1960 and was ready to join the police department. However, 60 Denver police officers had been sentenced to the Colorado State Prison in Canyon City over the previous few years for various felonies, many for pulling burglaries, safe jobs, etc., while on duty, in uniform, using police cars. So I looked to Phoenix and took the battery of tests for patrolman in June 1960. They included written, oral board, physical agility, medical and physiological. Captain Hershel Britten subsequently sent a letter inviting me to start the five-week recruit school beginning on August 22, 1960. I sold my house, quit my job and with very few dollars, drove my wife and two small children in my 1950 Oldsmobile (no air conditioning) to Phoenix, where we rented a very small one-bedroom house for about $65 a month. It had no AC, but was equipped with an evaporative cooler.

When I reported for duty, they advised that I couldn’t be hired without passing a polygraph test, which had been added after the tests I took in June. I sweated even more as Sergeant Charles Strong administered it, but I passed. The Academy class was held in a little house converted to a classroom on land where the present Academy is located. (The old Quonset hut was used as a storeroom then.) There were 33 in the class, and I think our pay was $345 a month with no overtime. Any work over 40 hours could be used later as compensatory time. There was no uniform allowance, but we were issued hat and breast badges, a used .38-caliber revolver, a gun belt with holster, handcuff and bullet cases, handcuffs, a sap and a flashlight. We bought our uniforms at a shop on the west side of Central Avenue, just south of Van Buren Street. (I think a guy named Thew ran it.) The uniform was dark blue wool trousers with two narrow sap pockets below the rear pockets for the sap and/or flashlight, a long-sleeved dark blue wool shirt for winter, a long-sleeved light blue cotton shirt for spring and fall, and a short-sleeved light blue shirt for the summer. We wore black clip-on ties, and hats were required when out of the patrol car.

The patrol cars were equipped with two buttons on the floorboard, one to dim the headlights; the other activated the siren and a knob on the dash was pulled to stop it. There was one radio frequency for the north side, one for the south and one “chase” channel for emergency traffic. Of course, portable radios were unheard of. Unless it was an extreme emergency, we drove to a pay phone and received our nickel or dime back when we called the City operator, who transferred us to the I-Bureau or MVD for registration and warrant checks. Our cars had no air conditioning until Studebaker Larks were purchased in the early 1960s, but not everyone got one right away.

We had no copy machines, and long-form departmental reports were typed by a clerk on premade packages, each made up of about six thin pages of different-colored paper separated by carbon paper. We wrote a report for every call: a short form, 5.5 by 8 inches, if it didn’t amount to much — such as when the complainant or activity was gone on arrival — and a long-form report if it was a serious matter. It was tough keeping the sweat off the paper while writing in the car with no AC in 110-degree heat. A worksheet was completed indicating all activity, and we were expected to write traffic tickets every shift. It was not a quota, but everyone knows that violations occur everywhere, every day.

Drunk drivers were taken to 17 S. Second Ave., where a civilian named Mr. Jones, who was contracted by the Department, was called in, day or night. He ran the breathalyzer, or whatever it was called then. If the drunk refused to blow in the machine, we strapped them in a big wooden chair and held their head until they exhaled into a cone-shaped device held to their mouth by Jones. Anyone arrested had to spend six hours in jail before being bailed out. They went to court the morning after their arrest, in a courtroom on the first floor of 17 S. Second Ave. That’s the courtroom where I first testified before Judge Pensinger on a red-light ticket I wrote. The judge had his eyes closed for part of the testimony given by the defendant, and I thought he may have dozed off, but he was probably concentrating on what was being said. She was a schoolteacher whom I had observed talking to several other women in her car as she drove through a red light. The judge found her guilty, informing her that I wouldn’t have written her a ticket unless she had run the light.

Phoenix had annexed south #9444 of the river bottom in June 1960, and many residents living there didn’t like it. After field training, my first beat riding solo was south of Dobbins Road, consisting mostly of South Mountain Park, which was dead on the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift. I first worked out of 17 S. Second Ave. or a storefront on the 100 block of West Jefferson Street, and later moved to a substation in the shopping center at Central Avenue and Roeser Road. Each shift consisted of a captain, a couple of lieutenants and their sergeants and patrolmen. The entire shift, from captain on down, changed from day to night to afternoon shift every two months, except once a year when we rotated after only one month. This was done so that no one would be stuck working the same hours during the same summer months or holidays year after year. I personally liked this arrangement because of the variety of work the three shifts provided. We reported to work half an hour early for briefing, for an eight-and-a-half-hour day.

Later, I was transferred to a relief squad where we worked the squad area south of the river bottom, west of about Seventh Street on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, then east of about Seventh Street on Thursdays and Fridays. This included 24th Street and Broadway Road, which at the time was called “Bloody Broadway.” There were very shabby bars and nightclubs, such as the Blackcat Walk-in, located there. We could always depend on a shooting or cutting on Friday nights. Broadway and 24th Street were the only paved streets in the area; all the surrounding streets were dirt, and there always seemed to be a lot of dust and dirt in the air. On Saturday night my squad worked the Downtown area, including the Duce. We had a two-man paddy wagon, which was a truck with a big metal box that held about 16 prisoners. We enforced the drunk-and-disorderly and vagrancy laws, so anyone found drunk or laying around on sidewalks or streets was picked up and booked, and we usually took several prisoner loads to jail on Saturday nights.

When I came on, we didn’t get any sick time off for six months. I got sick that first winter of 1960 and couldn’t afford to take off. My partner brought me to Memorial Hospital Emergency, where most of our business went unless someone went to the County Hospital. The lovely nurses there gave me a shot — no paperwork, no charges and I managed to get by without missing work. (I became ill another time after that, and Officer Edna Hurt, who was assigned to our jail, gave me a shot. Again, no charge, no paperwork.)

Speaking of the County Hospital, in 1960 it was located just off 35th Avenue around Durango, and was terribly antiquated and overcrowded. I remember bringing a prisoner there for treatment one night. The treatment and waiting areas were basically the same room and very small. When I came into the room with my prisoner, I saw that a doctor and nurse were working on a patient on a table behind a drape that separated them from the people in the waiting room. A drunk man on his hands and knees was trying to crawl under the drape, telling medical staff he wanted treatment, and the nurse was pushing him back out with one leg while assisting the doctor working on the patient on the table. Of course, I pulled the guy back and sat him down, telling him to wait his turn.

Being a pretty good shot, when we came on the day shift, 7 a.m. to 3 p.m., I was frequently called to the front desk, where the desk sergeant handed me a .22 rifle, a box of graphite bullets and a list of addresses where people had complained about pigeons. In full uniform, I went to the addresses, shot pigeons out of the palm trees and put them on the back floorboard of my police car. I took them to the City shop at 13th and Washington streets, and one of the City employees there took them home for several dinners.

Phoenix had its own jail on the top floor of 17 S. Second Ave., and a compound just south of Sky Harbor Airport where the prisoners served their time. The compound had a farmer who supervised a large garden where prisoners raised their own crops. A cook or cooks supervised the preparation of meals. They made great-looking cinnamon buns, which we were told had been baked with saltpeter. Officers didn’t eat them. The prisoners wore clean, pressed uniforms, and besides doing the farm and cooking work, they were assigned various details around the police station, City Hall, etc. They served their 30 days or so and were released back out on the street, where they got drunk and were arrested again. They all were given good medical care and many cycled their lives out that way. On the day shift I also remember getting calls to the jail to transport both men and women prisoners to the County Health Department located around 17th and Roosevelt streets, where they were treated for various venereal diseases. (I had to go to that same facility in about 2006 to get shots for a trip to Africa. It looked the same as it had long ago and brought back old memories.)

One of the first arrests I remember making while with my training officer was when we were called to a motel around Central Avenue and Broadway Road by an angry woman who reported that her husband was there with another woman. We arrested the husband and his girlfriend. I think they were charged with some code about being naked in the company of a person of the opposite sex, or possibly the “open and notorious cohabitation” law. I can’t recall which one, but they went to jail! (If you’re interested, I still have a copy of a 1960s legal opinion by the County attorney describing the elements needed to arrest for open and notorious cohabitation.)

I was promoted to detective in the summer of 1964, which meant a $40-a-month raise and a detective shield. We worked Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. until 5 p.m., but were occasionally assigned to work weekends, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. All detectives worked out of the main station at 17 S. Second Ave.

Editor’s note: Jim Humphrey retired from the Phoenix Police Department in January 1991 as a major.

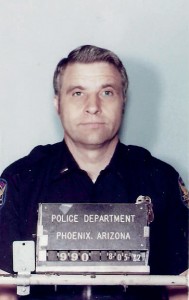

Carroll Cooley joined the Phoenix Police Department in April 1958 and during his career, he experienced two incidents that are noteworthy. In March 1963, Carroll was the detective who arrested and interviewed Ernesto Miranda, which resulted in the landmark 1966 United States Supreme Court decision known as Miranda v. Arizona. Since that decision was announced, thousands of officers across the United States have read what are commonly referred to as Miranda warnings or Miranda rights to suspects in custody prior to conducting interviews.

Carroll Cooley joined the Phoenix Police Department in April 1958 and during his career, he experienced two incidents that are noteworthy. In March 1963, Carroll was the detective who arrested and interviewed Ernesto Miranda, which resulted in the landmark 1966 United States Supreme Court decision known as Miranda v. Arizona. Since that decision was announced, thousands of officers across the United States have read what are commonly referred to as Miranda warnings or Miranda rights to suspects in custody prior to conducting interviews.

The other incident occurred on August 23, 1963. Carroll was shot in the head while pursuing an armed robbery suspect on foot. Carroll fully recovered from his injuries and rose through the ranks, eventually retiring as a captain on December 28, 1978.

After he retired, Carroll was employed as the director of computer-aided dispatching for all police agencies in Champaign County, Illinois, and also served as an adjunct professor #5547 in the Police Certification Program at the University of Illinois. In 1985, he returned to Arizona and was employed by the State of Arizona as an administrator with the Motor Vehicle Division before moving over to the Arizona Department of Public Safety. Carroll served in the Highway Patrol Division as a commander in District 16 and later oversaw administrative investigations until he retired in November 1985.

Since retirement, Carroll has served as a volunteer with two military support organizations, Employer Support for the Guard and Reserve (ESGR) and the United Service Organization (USO). ESGR is a Department of Defense office established in 1972 to promote cooperation and understanding between reserve component service members and their civilian employers and to assist in the resolution of conflicts arising from an employee’s military commitment. The USO strengthens America’s military service members by keeping them connected to family, home and country throughout their service to the nation, particularly during deployments.

Since retirement, Carroll has served as a volunteer with two military support organizations, Employer Support for the Guard and Reserve (ESGR) and the United Service Organization (USO). ESGR is a Department of Defense office established in 1972 to promote cooperation and understanding between reserve component service members and their civilian employers and to assist in the resolution of conflicts arising from an employee’s military commitment. The USO strengthens America’s military service members by keeping them connected to family, home and country throughout their service to the nation, particularly during deployments.

Carroll currently serves as a volunteer with the Phoenix Police Museum.

By Joyce Hubler

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.)

Richard White, #990, retired as a lieutenant in 1985 after serving 22 years on the Phoenix Police Department.

After moving to Phoenix in February 1961 from a small farming community in west central Illinois, Richard applied for a position with the Phoenix Police in October 1962. He was able to pass the physical and written testing, and was one of six candidates who passed the oral interview to be accepted. However, Richard was overweight and had until January 6, 1963, to meet the requirement. He enjoyed a Thanksgiving dinner of grapefruit, made the goal and started the Academy. At the time, it was situated at its current location but consisted of an adobe building and a metal building next to the range master’s house in front of the range.

The Academy lasted eight weeks, and each Friday recruits rode along with a patrol officer on Shift 1 or 2. Their recruit uniform was khakis and a big plastic enclosed name tag with “Recruit Officer” in full view — “You sure felt the public eyes on you,” Richard says. He was assigned to 800 and the day shift officer introduced him to the morgue, as they had evidence pickup duty at the old County Hospital, located at South 35th Avenue and West Durango Street. After entering through the front door and seeing an autopsy in progress, he managed to not lose it, but was told they could have used the back door to get the evidence to transport to the lab, which was located in Downtown Phoenix.

Thirteen recruits made it through the Academy, and Richard believes that five made it to retirement. Back then, the Department was on rotating shifts, changing every three months. His training officer was Ralph Chapman, who has since passed away, and they mostly rode the wagon. On May 5, 1963, they stopped a subject at South 10th Avenue and West Buckeye Road in reference to a homicide in the area. As it turned out, the subject was not the suspect, but an escapee from the State Hospital at North 24th Street and East Van Buren Street, who was not yet reported. He pulled a revolver from his waist and shot Ralph as he came around the wagon. Richard fled to the back as the suspect fired at him. He avoided injury, but the suspect was hit by their shots and died at the hospital. Ralph eventually recovered from a leg wound. Richard believes that the grace of God was with them that night, which was probably the worst moment of his career.

Richard was able to solo shortly after the incident and enjoyed the job to the fullest. He never had a day he didn’t want to go to work, and although he had assignments in many areas, he never worked Vice, Narcotics or Solo Motors.

In 1963, the Phoenix Police Department was just getting its first air-conditioned patrol cars and you had to use the pay phones for most of your business, including record checks and other information. You quickly learned to call the city operator to place your call so you could get the dime back; otherwise, it was costly and came out of your $330-a-month salary. There were no portable radios or computers, and only the teletype for out-of-area inquiry. Interestingly enough, officers were able to do so much without the modern conveniences of cellphones, portable radios and Mobile Data Computers. Richard remembers getting a call from a dispatcher to see if he still had contact with a car he ran the shift before, as it was wanted in connection with a homicide from another state. As luck would have it, he found it in the same area and was able to arrest the suspect at a local flophouse.

In 1963, the Phoenix Police Department was just getting its first air-conditioned patrol cars and you had to use the pay phones for most of your business, including record checks and other information. You quickly learned to call the city operator to place your call so you could get the dime back; otherwise, it was costly and came out of your $330-a-month salary. There were no portable radios or computers, and only the teletype for out-of-area inquiry. Interestingly enough, officers were able to do so much without the modern conveniences of cellphones, portable radios and Mobile Data Computers. Richard remembers getting a call from a dispatcher to see if he still had contact with a car he ran the shift before, as it was wanted in connection with a homicide from another state. As luck would have it, he found it in the same area and was able to arrest the suspect at a local flophouse.

Officers’ Code 7 (meal break) was 20 minutes, and they had to have a phone number to check off if they needed to be contacted. Officers and dispatchers both got to know the numbers. Shift 3 only had a few places to eat at, and with the rule that only one unit at a time could eat, it was hard to get in.

Richard enjoyed every assignment, but if he had to pick his favorite, his two times as a sergeant in the Special Assignments Unit (SAU, formerly known as SEU) would have to be the choice. Many were a learning experience and benefited him in all areas. He worked for a great bunch of supervisors and had a lot of great cops work under his supervision. There are many stories to be told and accomplishments to acknowledge, but the most satisfying ones were from good hard police work, such as finding a suspect vehicle with the bullet holes as broadcast, which led to booking the bad guy. That happened many times during Richard’s career, and he remembers most of them.

During his career, Richard saw the Phoenix Police Department grow, as well as becoming modernized with the computer age, going from no portable radios to many forms of communications. As he was leaving, we went on Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) and had the Modats (Mobile Data Terminals) installed in patrol cars. Richard was able to work on forming District Nine under Major Edens and saw the entire project become a reality, including the building and reorganizing the entire Patrol Bureau.

Richard retired on July 28, 1985, to take a job with Bullhead City, a newly incorporated city in Mohave County. His good friend from the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office, Tom Ennis, was the new police chief and had to form a complete police department by October 1, 1985. Retired Sergeant Fred Stuart was also a part of the formation, which included all facets, including hiring a total of 31 officers. They made the deadline, and to this day it is still a growing department.

Richard has had numerous jobs since leaving Bullhead City in mid-1987. He moved to Tucson in 1995 to be near his daughter and resides in Oro Valley, where he is a volunteer. His last job was a part-time position at Tucson City Traffic Court, which lasted over four years. In September 2000, Richard was blessed with a granddaughter and fully retired to become her babysitter, which he says turned out to be the best job he ever had. His granddaughter started high school this year, and he still enjoys helping her along and watching her participate in all of her activities.

Richard is always proud to say he retired from the Phoenix Police Department, and believes it is still one of the finest.

By Joyce Hubler

Detective (ret.)

Editor’s Note: Retirees play an important role in our PLEA family, so we’ve decided to include a “Where Are They Now?” feature to the Retirees’ page showcasing retired officers and their previous assignments and post-career accomplishments.

Ben Bacchi, #684, retired as a sergeant after serving with the Phoenix Police Department from February 15, 1960, to January 29, 1982.

Ben was born in and raised on Chicago’s South Side. After serving two years in the United States Army at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and returning to Chicago’s terrible winter storms, he contacted Sergeant Lowell Hicks in Phoenix regarding a position with the Phoenix Police Department. He had enjoyed Phoenix as a young kid driving to California on a family vacation in 1947.

Ben started the Academy in 1960 with some great classmates, including Hugh Ennis, Larry Sheets, Milo Kaufman and a few other recruits. On his first day on the job in the field, with Dan Barker as his training officer, after briefing they drove to Rainbow Donuts on East McDowell Road; he was finally a real cop! He next spent five years in patrol working East Phoenix and transferred to Narcotics in January 1965, then to the old General Investigations Bureau in June 1965. Ben was promoted to sergeant in April 1970 and kept that rank until his retirement in 1982.

Ben enjoyed working with some great guys and gals and felt a special accomplishment in investigating and successfully prosecuting individuals in rape and molestation cases. His saddest day was the loss of Motor Officer Al Blum in December 1970. Ben knew Al from working off-duty jobs together and enjoyed Al’s stories about when he worked in Kansas City, Missouri. The week prior to Al’s death, Ben’s youngest daughter had been begging him to take her to the Busy Bee, a cop’s lunch counter in the downtown area, because she had heard so much about it! Well, he took her there, and Al happened to be there eating. Ben introduced Al to his daughter and Al talked to her, making her feel great. What a guy, and what a terrible loss.

After leaving the Department on January 31, 1982, Ben and several other Phoenix police officers followed retired Chief Doug Nelson to join the security program at the new Palo Verde nuclear plant. Ben served as a captain and shift supervisor at the startup of the plant and retired from Palo Verde in May 1992.

On May 18, 1992, Ben took the position of Mohave County probation officer in Bullhead City, Arizona. He began as a deputy I, handling adult caseloads from the superior court and once again enjoying the camaraderie of the other deputies #8010 he worked with. While Ben was able to help some of his probationers, others just couldn’t overcome their drug and alcohol addictions. He has since met several of his former probationers in the Bullhead City area who have thanked him for helping them get straight. Ben said it was extremely heartwarming to be able to help another human being, just as it was when he was a cop who helped a victim get some closure. Ben retired from Mohave County as a deputy II on April 4, 2003.

In 2003, Ben was asked to become a member of the Clark County, Nevada, Coroner’s Office in Las Vegas. He held the position of investigator and was responsible for handling deaths in the Laughlin and Searchlight areas, as well as the vast desert in between. As in the past, he once again worked with some great people and a good boss, Mike Murphy. However, by 2008, Ben was starting to get tired of those late night and early morning phone calls and finally retired, sort of, for good.

However, since 2002, Ben has been a member of the Volunteer Homeland Reserve Unit, started by retired New York Police Department Officer Ted Farces. This unit of retired law enforcement and military personnel was created after 9/11 by Ted to assist police departments in the Arizona, Nevada and California tri-state area in the event of another 9/11-type attack. Currently, it assists agencies with events that require additional (unpaid) police services, drawing on the knowledge and experience of years of police work from departments throughout the country, including the Las Vegas Metro, Bullhead City, North Las Vegas and Fort Mohave Indian Police Departments. Ben says it is very interesting to hear cop stories from the different jurisdictions.