Secretary's Message

Secretary

jmaxwell@azplea.com

At the time of this writing, there are currently 2,695 total sworn police officer positions in the City of Phoenix Police Department. Of that number, there are only 996 total officers patrolling the streets, responding to calls for service, investigating violent crimes, responding to medical calls for service and conducting community policing. When will the bleeding stop! Just last year, the Department lost 274 sworn positions to retirement, resignation, termination and lateraling to other agencies. There are already 137 officers scheduled to leave before July.

With many police officers being tenured on the Department due to a hiring freeze for many years, you must ask, “How many will we be losing this year?” There is a minimal hiring bonus, minimal retention bonus and minimal lateral bonus to entice qualified people to work here. Other police agencies are offering higher hourly pay with bonuses across the board, advertising in person, on social media and telling applicants, “Come work for us and leave Phoenix P.D.” They use propaganda slogans like, “Our city council cares about our police officers” and “Our police department has your back.” Guess what — it’s working!

Phoenix has a population of approximately 1.7 million citizens and only 996 patrol officers serving them.

The Phoenix Police Department is currently in the process of a patrol-wide rebidding process/manpower reallocation, or whatever fancy term you want to label it. When you start to move detectives from investigative bureaus and eliminate criminal investigative functions to fill vacancies in the patrol, we are bleeding. The Department has eliminated the entire auto theft bureau, eliminated training staff (including the entire driver training staff and the entire rifle detail), removed burglary detectives and eliminated numerous community action and neighborhood enforcement officers. With the Department eliminating some of these details, they have lost some of the most qualified subject-matter experts in the state. These are just some of the positions that are heading back to the street to answer calls for service and putting on the uniform. PLEA had questions about staffing and caseloads on current detectives, who will be absorbing the cases of other detectives who are being forced to leave (sounding the alarm).

Executive Assistant Chief Michael Kurtenbach asked PLEA, “Where should I pull bodies from to go to patrol?” That is not PLEA’s position to make that decision. We have been seeing this coming for over a couple of years now, and command staff has been reporting the critical bottom-line number of officers on patrol, but it keeps changing. It started at 1,096, and now the Department is claiming we cannot get below 1,000 on patrol. Phoenix has a population of approximately 1.7 million citizens and only 996 patrol officers serving them. The community should be disgusted to see the recent attacks on our officers, most notably, nine being shot on February 11 by a crazed gunman who had no regard for human life.

On March 13, two officers were shot at in their patrol vehicle, with one of them being struck by gunfire. This job is hard enough running from call to call with minimum staffing on every shift in every precinct. Officers need to make a deliberate decision to be safe. Do not advise on any call, ever! The most mundane and normal call can turn into a fight for your life, and you don’t want to be required to have to justify your actions on why you didn’t wait for backup.

May 15 was National Peace Officers Memorial Day. Don’t forget all our brothers and sisters who made the ultimate sacrifice. Be safe!

As I’m typing away on my keyboard, I’ve got a smile on my face, a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye as I realize that this will be my last official writing for an organization I’ve been part of for the past 26 years. As a child growing up, I would never have imagined that half a century later, I’d be 2,500 miles away from the place I envisioned living my life, and working in a profession that was a playtime activity based on Adam-12. Events that occurred in my life and the lives of family members led to an Arizona vacation, then a decision to leave New Jersey and move to Phoenix, which paved the way for me to become a Phoenix police officer.

As I’m typing away on my keyboard, I’ve got a smile on my face, a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye as I realize that this will be my last official writing for an organization I’ve been part of for the past 26 years. As a child growing up, I would never have imagined that half a century later, I’d be 2,500 miles away from the place I envisioned living my life, and working in a profession that was a playtime activity based on Adam-12. Events that occurred in my life and the lives of family members led to an Arizona vacation, then a decision to leave New Jersey and move to Phoenix, which paved the way for me to become a Phoenix police officer.

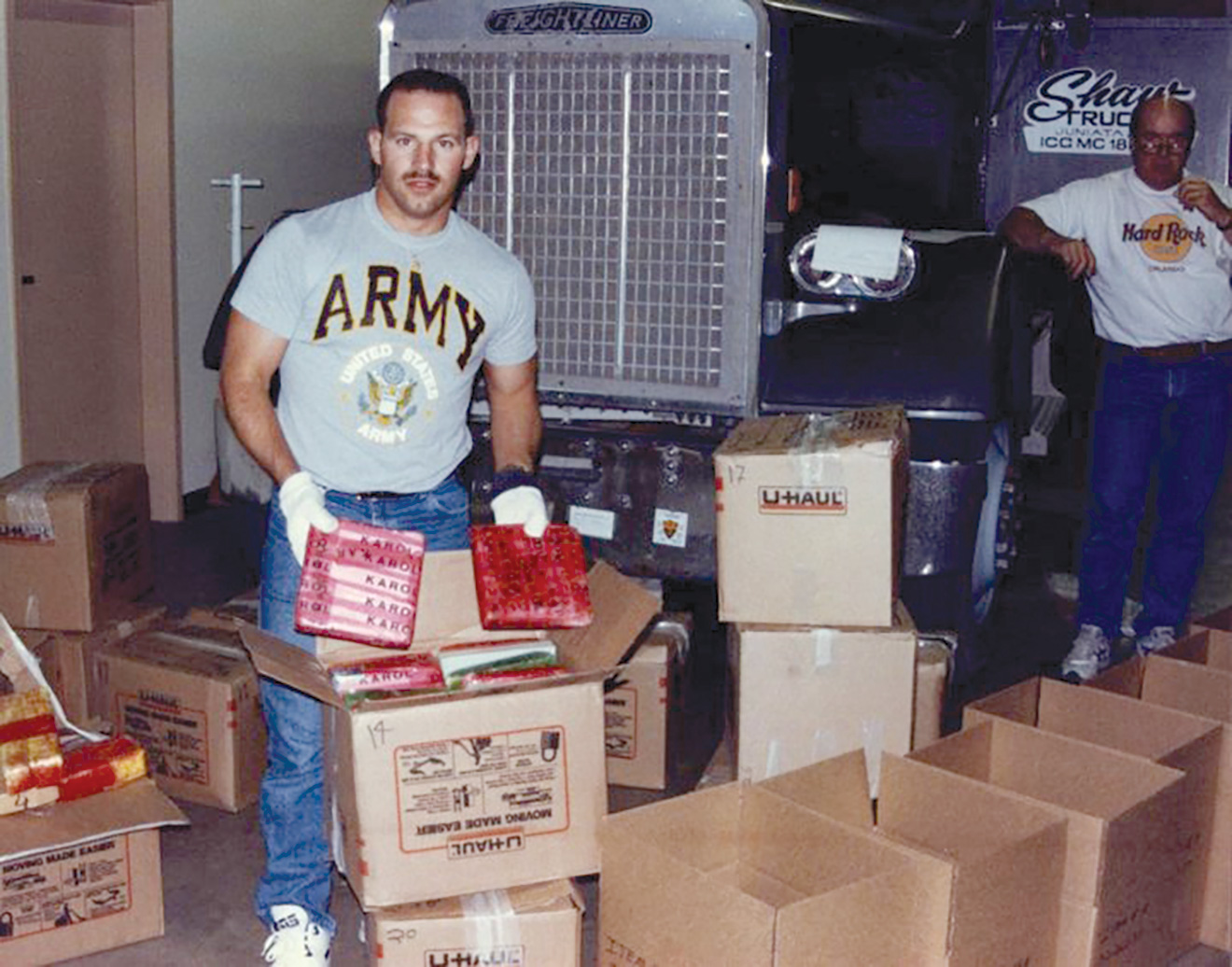

After visiting Arizona twice in 1988, I tested for Scottsdale in the spring of 1989. I completed my oral board and never heard back from them. Arizona became my new home that fall, and a year later, in 1990, my Military Police unit was activated for Desert Shield, which became Desert Storm. The deployment changed my life course and reaffirmed my goal of becoming a police officer. In November 1991, I finally had the opportunity to test for the Phoenix Police Department, which was considered the premier agency in Arizona. Instead of attending my 10-year high school reunion in New Jersey, I took the written test with hundreds of others at the old Civic Plaza and proceeded to the Academy for my physical fitness test. The MCSO deputy who scored my sit-ups said I did not complete the required number. Since I was on active military duty, my first thought was to challenge him, because I worked out daily and made it a point to be able to pass the PT test with well above the minimum reps for both push-ups and sit-ups. However, the soldier in me knew a challenge could work against me, so I retested in January 1992, passing with no issues. Then, Phoenix had a hiring freeze, so I tested with Chandler and the Pima County Sheriff’s Office, only to be put on waiting lists.

It has been an honor and privilege to serve the membership over the past 20 years, working to right wrongs and fighting the good fight.

By September 1992, Phoenix began hiring again, but I opted to use my GI Bill benefits to attend college. My thought process was that secondary education would make me more competitive in the hiring process. In the spring of 1994, I tested again and was hired in late September. I started the Academy on October 3, 1994, with Class 265, graduated on January 13, 1995, and was assigned to 500 to start the FTO program. 500 would be home for most of my career; I spent my first seven and a half years on second shift, including four and a half years on an FTO squad. During my time as an FTO, former PLEA President Ken Crane and I worked as partners, and he persuaded me to get involved with PLEA as a representative. The furthest thing from my mind when I became a cop was any aspiration of being a labor representative; however, as it has been said, “Everything has a reason for happening,” and happen it did. During that same time period, another life event occurred: I met my wife, Dena. When we started dating, she was a single mother, and when we decided we were going to get married, I opted to go to third shift to spend more time with her and my daughter and son, which is where I spent the next nine years of my career. It’s enough of a challenge raising a family when you’re a cop working holidays, getting home late due to holdover and missing family events because of shift conflicts or the inability to get time off. However, the move allowed me to attend recitals, concerts and other school events, T-ball and soccer games, and scouting events. I’m grateful for that family time we shared.

In 2009 I was appointed to the PLEA Board to fill a vacancy, then ran for and was elected to a trustee position. I became chair of the Board within a year, and in 2011, former PLEA President Joe Clure asked me to run for secretary, which I did. That August, I moved into a full-time release position in the PLEA Office. When you combine the challenges of being a cop and raising a family with being a police labor representative, it’s a whole different game when you are actively involved in the organization, and that compounds when you become a Board member. Your cellphone becomes an appendage, with what can seem like nonstop calls, text messages and emails coming in at all hours, regardless of whether you’re working, on your days off or on vacation in the mountains. Why is that? It’s because you are a resource for people seeking your guidance and wisdom in their moment of need. It also means callouts in the middle of the night or on weekends and days off while taking standby.

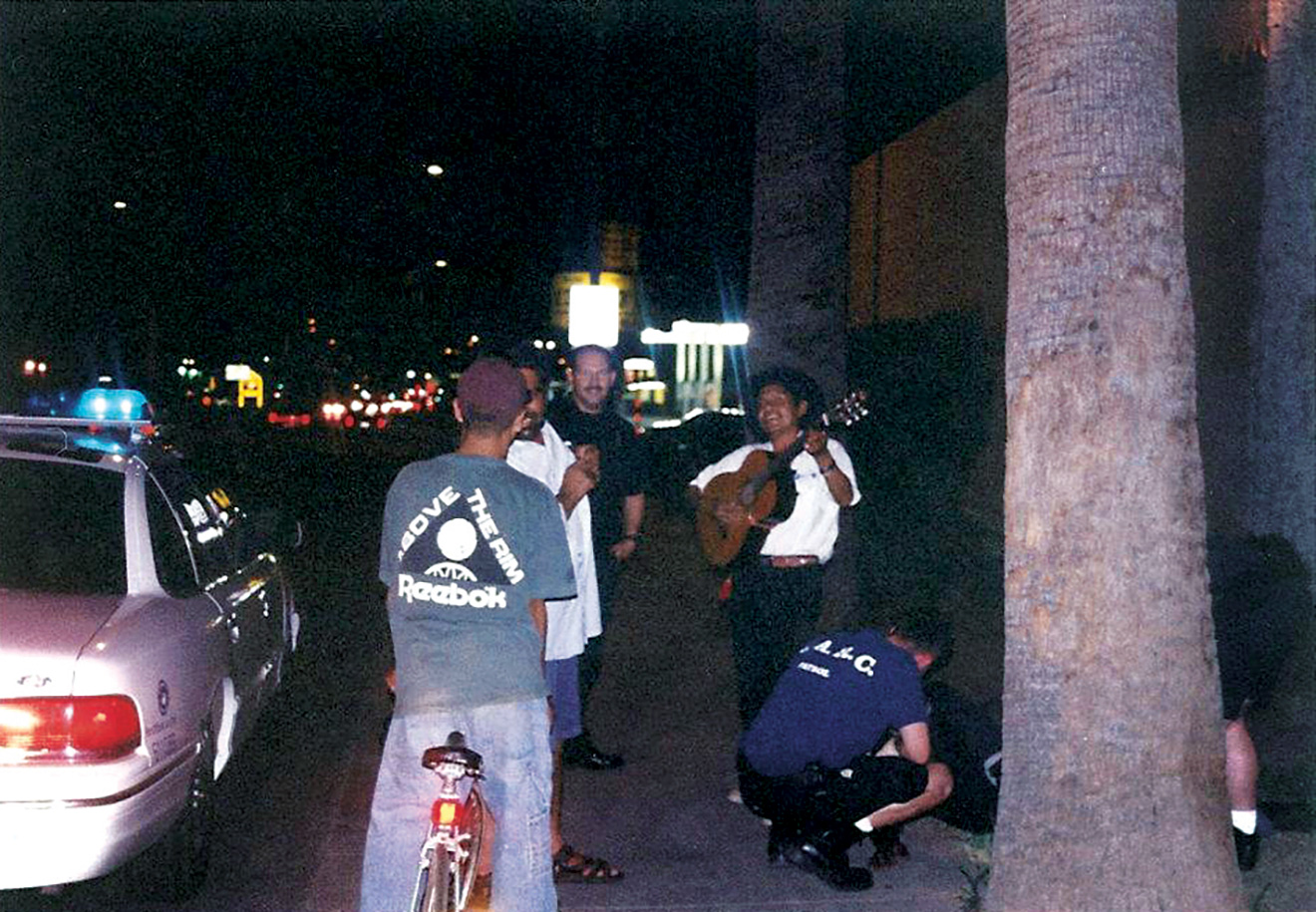

In June 2012, I spent two weeks assigned to 600 after the first Goldwater injunction; then, in May 2013, I went back to 500 after the second one. After almost a year and a half, I opted to go to 700 in the 2014 rebid and stayed there for nearly two years, until the Arizona Supreme Court overturned the Goldwater injunction in September 2016 and I returned to PLEA. During my time in 700, I worked the former 52 and 53 areas, where I had cut my teeth and spent most of my career as a beat cop. I felt comfortable and confident working in my old backyard. The most challenging three years and four months of my stint as a PLEA Board member were during the Goldwater injunction, because I remained on a Patrol squad and did not make it back to the office. In addition to working 10-hour-plus shifts, I was handling PLEA business prior to and after my shift, as well as on my days off. Having said that, if I didn’t have a full-time release position, I would have opted to stay in Patrol, because it’s what I loved doing, even though it has drastically changed within the past few years. Despite the challenges during those years, there were some good times, and I got to push my limits as a street cop thanks to another partner, Kevin Wilson, who, like me, became a PLEA rep and Board member. We got into several potentially dangerous situations during the time we worked and rode together, but we made numerous felony arrests, including some that were tied to very complex cases. We did not make any excuses for pushing the limits; that’s what happens when you’re a street cop at heart and love the thrill of the hunt and chase.

I never had the desire to promote. Between my deployment to Saudi Arabia during Desert Storm and my active-duty assignment on the Task Force, I had my fill of supervising, including a few problem children who taxed my patience. During my time on the Department, I worked for a number of good supervisors, but I also worked for my share of bad ones. I saw the flaws of a system that promoted test-takers versus leaders and those with the solid tactical base of a street cop. Granted, I could have become part of the solution by promoting, but for me, it was more challenging and rewarding to become part of the solution as a PLEA rep. That gave me the ability to hold both bad officers and bad supervisors accountable for their actions, whether it was a simple mistake of the heart or blatant misconduct. Bad officers got walked out the door, while officers who made mistakes, or were alleged to have made mistakes but didn’t, were vilified at Use of Force and Disciplinary Review Boards or meetings with the Police Chief. Bad supervisors or supervisors who bullied their troops were also dealt with, while good supervisors who supported their troops, sometimes against the will of their superiors, were rewarded. Speaking of rewarding, going head-to-head and taking to task a bullheaded, overzealous former “Chief of Police” was one of the more rewarding things I did as a rep. As I always tried to explain to supervisors and managers who were willing to listen, it wasn’t personal; it was business, and it shouldn’t interfere with working together for a common cause and goal, which we signed up for when we became cops.

When I was hired, Phoenix was the police department everyone wanted to work for but couldn’t. Hiring standards were well above AZ POST minimum; the Academy had a paramilitary format that challenged us and weeded out those who couldn’t meet standards. Not everyone made it through the FTO program, and not everyone who managed to go solo was able to keep up with the pace afterward and complete probation. While we worked hard and consistently got our asses handed to us in terms of call volume combined with holdover on the weekends due to multiple violent crime scenes, we had fun doing it. We were still allowed to do police work, and it involved going after people who committed crimes and putting them in jail, sometimes after a vehicle or foot pursuit. Pushing the limits to the edge was common and, thankfully, most of the supervisors I worked for and under were street cops at heart and did what they needed to do to make sure overzealous commanders didn’t come after us.

While police work itself has remained relatively unchanged, technology has affected it positively and negatively. When I came on, our issued Glocks did not have weapon light rails, and our gun belts, holsters and accessories were heavy, synthetic leather. Most of us carried a rechargeable Maglite or Streamlight that doubled as an impact weapon, and while some of us were designated as shotgun operators, we didn’t have Tasers or patrol rifles. Pagers were common and some of us had cellphones. Our patrol vehicles were Chevrolet Caprices, but they had halogen rotator emergency lighting and no reflective markings. They did have Mobile Data Terminals, which allowed us to receive and disposition calls, run records checks on people and vehicles, and complete false alarm and field interrogation cards; however, they had less functionality than the most basic smartphones of today. We either handwrote our reports and turned them in at the front desk, or dictated them to a live secretary or a recorder called the Voicewriter for eventual transcription and entry into PACE, which was much easier to navigate than RMS. Booking paperwork was filled out by hand and could be done on the hood or trunk of a patrol car at the scene before heading to the “Horseshoe” at the Madison Street Jail, where it would be reviewed by a police assistant before you turned your prisoner over to MSCO personnel. Over the years, technology made some processes easier while hamstringing and lengthening others.

Caprices gave way to Ford Crown Victorias and vehicle-mounted laptops that were difficult, if nearly impossible, to remove to get the intended function out of them. Every marked patrol vehicle had a less-lethal stun bag shotgun, and each squad had designated Taser operators until everyone in Patrol was issued a Taser. 2001 marked the implementation of the Patrol Rifle Program, full-sized 20-inch-barrel “politically correct” Colt AR15 HBAR Sporters. It would take a few years for common sense to work its way into the program, upgrading to Colt LE6920 Carbines with 16-inch barrels and collapsible stocks. In 2005, we tested our first Tahoe with much-improved emergency lighting and internal gun racks. As the Crown Victoria was slowly phased out, Tahoes were integrated into the fleet. We used the Chevy Impala purely for cost savings and to get the fleet modernized. Gun racks were moved to the front of the Tahoes for easy access, while laptops slowly improved. Eventually, we had console-mounted printers and scanners for use in conjunction with TRACS, which is how we wrote crash reports and issued citations and exchange cards. In 2013, after over a decade of testing and evaluating various emergency lighting packages, we finally had 100% LED emergency lighting on our Tahoes. We continued to improve the interior setups, eventually convinced City bean-counters that an all-Tahoe fleet would save money in the long run based on vehicle life cycle costs, and stopped purchasing Impalas and the reintroduced Caprice. RMS replaced PACE, and many of us still believe PACE was a much better system despite it living on borrowed time. Some of us still affirm that a fraction of the money dumped into RMS could have prolonged PACE, but the City and Department hate to admit when they’re wrong, as they’ve been with the entire RMS fiasco. Body-worn cameras went citywide from a pilot program in Maryvale and continue to prove what we knew before we had them: Phoenix police officers are professional, do a good job and use reasonable force when necessary to conduct our mission. They also show that we deal with violent individuals on a more frequent basis than we ever have and resort to lethal force when there are no other options available, despite the rhetoric heard from anti-police activists and members of our City Council.

Caprices gave way to Ford Crown Victorias and vehicle-mounted laptops that were difficult, if nearly impossible, to remove to get the intended function out of them. Every marked patrol vehicle had a less-lethal stun bag shotgun, and each squad had designated Taser operators until everyone in Patrol was issued a Taser. 2001 marked the implementation of the Patrol Rifle Program, full-sized 20-inch-barrel “politically correct” Colt AR15 HBAR Sporters. It would take a few years for common sense to work its way into the program, upgrading to Colt LE6920 Carbines with 16-inch barrels and collapsible stocks. In 2005, we tested our first Tahoe with much-improved emergency lighting and internal gun racks. As the Crown Victoria was slowly phased out, Tahoes were integrated into the fleet. We used the Chevy Impala purely for cost savings and to get the fleet modernized. Gun racks were moved to the front of the Tahoes for easy access, while laptops slowly improved. Eventually, we had console-mounted printers and scanners for use in conjunction with TRACS, which is how we wrote crash reports and issued citations and exchange cards. In 2013, after over a decade of testing and evaluating various emergency lighting packages, we finally had 100% LED emergency lighting on our Tahoes. We continued to improve the interior setups, eventually convinced City bean-counters that an all-Tahoe fleet would save money in the long run based on vehicle life cycle costs, and stopped purchasing Impalas and the reintroduced Caprice. RMS replaced PACE, and many of us still believe PACE was a much better system despite it living on borrowed time. Some of us still affirm that a fraction of the money dumped into RMS could have prolonged PACE, but the City and Department hate to admit when they’re wrong, as they’ve been with the entire RMS fiasco. Body-worn cameras went citywide from a pilot program in Maryvale and continue to prove what we knew before we had them: Phoenix police officers are professional, do a good job and use reasonable force when necessary to conduct our mission. They also show that we deal with violent individuals on a more frequent basis than we ever have and resort to lethal force when there are no other options available, despite the rhetoric heard from anti-police activists and members of our City Council.

I have many people to acknowledge and thank for what I have achieved. First and foremost, I give thanks to God for looking out for me every step of the way during this amazing journey, but there are countless others, many of whom I’ve alluded to in the articles I’ve written over the years. From childhood into adulthood, there were many cops who left impressions on me. They include cops I encountered growing up, the beat cops who’d stop in at my dad’s shop and a neighbor who was a patrol sergeant on our township police department. There were other cops from various agencies I met and worked with after my enlistment in the Army National Guard and service in two different Military Police units, and I met others during training and activations. During my three-plus years of active duty on the Arizona National Guard’s Joint Counter-Narcotics Task Force, I met more cops and federal agents. Those experiences and the knowledge I gained firmly set the wheels in motion for a major life and career change. As I was laying the groundwork and contemplating that change and the decision to become a police officer, there was unconditional support from my immediate and extended family and friends. My parents, sisters, grandmothers, aunts, uncles and cousins were there for me through the entire process and beyond. Longtime family friends and personal friends, including some from high school, others I met afterward, my “Whiskey Bravos” and other Army buddies, some of whom served or continue to serve in law enforcement, have all been a part of my support network. I met my wife when I had five years on the job and she has been there through thick and thin. She and my daughter and son have always understood the complexity of the job and supported and encouraged me during the best and worst times of my career since they’ve been a part of my life.

The past 26 years have been awesome, and I’m glad I had the opportunity to be part of a great law enforcement agency before it was dismantled by spineless politicians and managers who lost touch with their street cop roots. I always tried to do the right thing for the members of the community whom I ultimately served, and I had the honor and privilege to work with some amazing cops over those years — some who are still with us, some who left this Earth too soon, others who have retired, and still others who are doing bigger and better things at other agencies because of the skills they gained working for Phoenix. It has been an honor and privilege to serve the membership over the past 20 years, working to right wrongs and fighting the good fight when necessary. Having said that, it also has been an honor and a privilege to have served as an elected Board member under four different PLEA presidents over the past 12 years. While we may have had philosophical differences at times, we all worked together for the greater good of the membership. Farewell, my friends and colleagues; it has been a helluva ride! 6024 is 10-7!

With a tumultuous 2020 finally behind us, we are entering the unknown of 2021 and what will be my last three months as a Phoenix police officer. In my 26 years of what has been an amazing career, I am still dumbfounded as to what has become of a proud profession because of politicians and activists. I firmly believe that it was former president, Barack Obama, who started the “War on Cops” after he interjected himself in the arrest of Henry William Gates, which occurred on July 16, 2009, claiming “the cops acted stupidly” without knowing all the facts of what led up to the arrest. When the leader of the most powerful nation in the world makes a preposterous statement like this, it is a green light for all to follow.

Councilmember Garcia’s anti-rule of law and anti-police stance has been clear since his activist days with Puente.

Five years later, on Obama’s watch, we had the infamous Michael Brown incident in Ferguson, leading to the “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” myth perpetuated by Black Lives Matter and which has become the clarion call of police reform activists. Two years later, on July 7, 2016, five Dallas police officers were shot and killed with nine more injured, and 10 days later, two Baton Rouge police officers and a Baton Rouge deputy sheriff were killed, and three other officers were wounded in ambush attacks attributed to the anti-police rhetoric spewed by Black Lives Matter. That rhetoric continued, and the summer of 2020 was one of protests and riots sparked by the death of George Floyd while in the custody of Minneapolis, Minnesota, police and other high-profile cases, including Breonna Taylor and Jacob Blake. The key element I have seen in these cases has been judgment of the involved officers in a trial by media long before all the facts of the investigations are known.

Phoenix isn’t immune to the rhetoric, and while we’ve had several high-profile incidents of our own, a lot of the rhetoric comes from our elected officials. Mayor Gallego and Councilmember Carlos Garcia have been embraced and supported by those involved with the “defund the police” movement. Recently, this all came to a head after an allegation that a Phoenix police officer made a “credible threat” against the mayor, and media outlets ran with the story. Never one to let a crisis go to waste, Garcia was the star of the show in one media account of the incident, claiming that PLEA’s Facebook posts “make the issues personal.” Councilmember Garcia’s anti-rule of law and anti-police stance has been clear since his activist days with Puente. He is the one who hijacked the City Council meeting after the 2017 Trump rally, then shortly after he was elected to the Council, his interaction with two ASU police officers was memorialized on body-worn camera footage after they stopped him for suspended plates in Downtown in 2019.

In July 2020, Garcia made blatantly false statements regarding the July 4 officer-involved shooting with James Garcia, and the false narrative he and Poder in Action pushed about how PLEA decides who is selected for school resource officer positions was promptly shut down by Assistant Chief Mike Kurtenbach during a City Council meeting during the summer of 2020. The look of surprise on his face was of a Pow! Zap! comic book cloud. When so-called “leaders” attack our members and the law enforcement profession without merit, we’re going to call them out on it and let everyone know where they stand. It’s ironic that Councilmember Garcia reminds me of another guy with the same last name with a similar agenda: radically changing the Phoenix Police Department due to issues that didn’t really exist, but were fabricated to make it look like there were problems that needed fixing, and he was the only one who had the power and ability to do so. As was the case with the other Garcia, standing up for and defending our members are far from personal; it’s business.

The same article laid out the conflict between Mayor Gallego and PLEA. In 2014, while she was a City Council member, during a meeting regarding approval of our contract, she made a motion to increase our pay, then promptly voted against her own motion, setting the tone for future behavior. In 2017, PLEA met with the mayor and every City Council member to discuss staffing and manpower concerns. At the time, the mayor was a Council member, and although receptive to our concerns, she didn’t respond with any clear or defined commitment to resolve those issues. Mayor Gallego has now been in office for almost two years, and she has yet to show any commitment or support to Phoenix police officers. Last February 24, after proposing an “auditor model” of civilian oversight, as with our 2014–2016 contract, she did a 180-degree turn and supported Councilmember Garcia’s “Plan B,” which PLEA knew would be bad for the City and our members. As mentioned above, in late May 2020, violent protests broke out in Downtown Phoenix and carried into the first week of June. On May 30, during a night of protesting, several Phoenix Police Department Tahoes had their windshields broken and tires slashed. Windows on the Sandra Day O’Connor Courthouse and several businesses were broken out. On June 2, the mayor posted on her Facebook page that she appreciated the work and commitment to the community shown by Neighborhood Services and Public Works after spending several days cleaning up the damage. However, there was absolutely no acknowledgment or mention of gratitude to the hundreds of Phoenix police officers who had been out in the triple-digit heat in full crowd control gear for nearly a week preventing additional damage, as well as protecting those who were protesting. On June 9, she posted on Facebook that City Hall was lit with crimson and gold to honor George Floyd! On June 29, PLEA President Britt London sent a letter to the mayor and City Council to stand with Phoenix police officers and oppose the “defund the police” movement. As this issue goes to print, we have yet to hear her, Garcia, Laura Pastor or Betty Guardado voice any sort of support for Phoenix police officers.

Social media works both ways, and PLEA has no control over what our supporters and followers say about Councilmember Garcia or the mayor, but maybe Garcia needs to look in the mirror and see why he gets the influx of angry calls and emails, or the alleged threatening comments via phone, email and social media. PLEA has been the recipient of similar actions after calling out the groups Councilmember Garcia aligns with on social media about the outlandish claims and outright lies they have made and told about PLEA and our mission. PLEA has never been opposed to accountability, and as mentioned ad nauseum over the years, we have walked plenty of Phoenix police officers out the door and helped them surrender their AZ POST certification when their conduct was egregious enough to warrant it. All we’ve ever asked for is that due process run its course and that the disciplinary process be fair, unlike the radical changes Garcia has tried to push through while trying to implement the new Office of Accountability and Transparency. PLEA knows through polling that the majority of Phoenix voters support the Phoenix Police Department. This is totally contrary to the small group, which has repeatedly shown up at City Council meetings behaving like spoiled, petulant children who don’t get their way. Instead of looking out for the best interests of the majority of Phoenix residents, we have a mayor and members of the City Council who have chosen to cater to a few squeaky wheels. I believe that because of PLEA’s efforts on social media, the silent majority who support police and law and order are finally becoming more vocal.

Absent law and order, there is chaos, and those calling for defunding and outright eliminating police departments are finding out how quickly the tide can turn against them. We’ve seen accounts of elected leaders aligned with the “defund the police” movement in some cities hire private security or utilize the very law enforcement assets they condemn in order to protect them because of concerns about their safety. In many of those same cities, residents of minority and low-income neighborhoods are asking for more police officers because they are the people who suffer when criminals are allowed to prey on them because of a decreased police presence. As 2020 drew to a close, while the city continued to grow in population, Phoenix saw an increase in violent crimes, including homicides. This occurred as the Phoenix Police Department continued to lose personnel through attrition while failing to meet recruiting goals for the third straight year. Despite the anti-police rhetoric and lack of support from elected leaders and community members, the men and women of the Phoenix Police Department will continue to do the job they willingly took on. On that same note, I, along with the rest of the PLEA Board, will continue to stand up and defend our members when they are wronged.

As we draw to the close of another year, an election year at that, two thoughts set firmly in my mind: 2020 has been a very challenging year for the law enforcement profession due to a few select use-of-force incidents the mainstream media has chosen to showcase without providing all the information; and activist groups pushing an anti-police agenda capitalizing on those incidents and rioting in major cities across the country, including right here in Phoenix, Arizona. Yes, I called it rioting because there is a distinct difference between peaceful and unlawful assembly and damaging property, looting businesses, and burning vehicles and buildings. I’m no fortune teller, but I believe that regardless of the outcome of the presidential election, lawlessness, contempt for the police and additional limits on force options will continue. The end result will be veteran officers retiring, unmet recruiting goals and less proactive police work, all which will affect communities, particularly low-income and minority communities that already have high crime rates.

Regardless of the outcome of the presidential election, lawlessness, contempt for the police and additional limits on force options will continue.

While I lived in predominantly white, upper-middle-class neighborhoods, I can say that I grew up in the inner city. I was 9 when my dad opened and ran his own business in Paterson, New Jersey, and when I was in eighth grade, instead of attending our local township high school, I opted to attend and graduated from what is now known as the Passaic County Technical Institute (PCTI), which began as the Paterson Vocational School. I worked for my dad until I graduated high school, and, as it was in 1973, Paterson is still beset with high poverty and crime rates. Many of my classmates and sports teammates were from Paterson and Passaic, another large city with similar issues. One thing I learned at an early age was to treat everyone with respect and dignity, regardless of their skin color or the neighborhood they lived in.

After Tech, the next melting pot I jumped into was the Army National Guard. Experience in two military police units and a stint as an instructor at the New Jersey Military Academy set the wheels in motion for a major career and lifestyle change: law enforcement. In the 14 years I served as a citizen-soldier, I met and worked alongside many cops from a variety of municipal, county, state and federal agencies. Those cops were as diverse as the units I served in, but we had similar values and virtues: service and giving back to our community. With the advent of the internet and social media, I learned of a number of my PCTI classmates who, like me, opted for law enforcement careers over trades.

Before my Academy graduation, I was asked to choose which of the six precincts I wanted to serve in. At the time, Phoenix had a population of around one million people spread out over approximately 400 square miles with a dense urban core, less densely populated suburban areas, open desert and farmland. Each precinct had unique #7860 geographical features, parks, residential areas and commercial properties. I could have gone anywhere in the city: older neighborhoods from the 1950s, world-class resorts, multimillion-dollar homes at the base of and along the sides of Camelback Mountain, open desert and large residential lots, horse properties and massive homes backing up to the mountains, or others with older homes, large apartment complexes, industrial parks and some active farmland.

I chose to work in a precinct that resembled the area where I grew up, the inner city, with established, older neighborhoods, multiple historic districts, large parks and a growing downtown with skyscrapers. However, the precinct also included some of the worst crime-infested and violent neighborhoods. They had low-income housing, public housing projects and neighborhoods where drug sales were rampant. Multiple drive-by shootings between rival street gangs were the norm on the weekends. This was a precinct where I believed that I could make a difference in the lives of the people who lived there. The residents who lived in these neighborhoods included blue-collar workers and professionals, but there were also many minorities, including Blacks and Hispanics. Many of the Hispanics were illegal immigrants who simply wanted to work and send money to their families in Mexico, but there was also the criminal element. Those who exploited their own people by stealing from, assaulting or finding other ways to victimize them and others living in the area. We also had a growing refugee population from war-torn Africa, Bosnia, Iran and Iraq.

I took my share of domestic violence reports from women of color who were beaten but didn’t want the offender arrested because he was the breadwinner. East Van Buren Street was a hotspot for prostitution, and I took my share of assault and sexual assault reports from prostitutes who were brutalized by pimps and johns. After taking a juvenile sexual assault call at a local hospital, I got together with fellow officers and put together a case against a pimp from California who kidnapped a Phoenix teenager and put her to work on the street turning tricks. She was terrified, and I could see the fear in her eyes when she identified him in a photo lineup and agreed to testify against him in court about the awful things he did to her. In that same moment, I saw the gratitude in her mother’s eyes, knowing he would soon be off the street, unable to harm her daughter anymore.

There were countless times when I stood by crime scenes on the street or in the hospital trauma room where the lifeless bodies of teens and young adults of color lay after bleeding out from being shot multiple times. Meanwhile the screams and cries of hysterics from their families echoed in the neighborhood and hospital corridors after learning the fate of their loved one from a cop or social worker. Many of the homes and apartments I went into during my career had dirt yards and no air conditioning, evaporative coolers if they were lucky. Children slept on ratty mattresses placed on the floor with threadbare sheets and torn blankets in filth that I wouldn’t let my dogs live in. The public housing projects in the areas I worked, the Sidney Ps, Krohns and Duppa Villas, were like resorts compared to the CCPs, Brooks-Sloate and Alabama Avenue Projects some of my classmates and friends from Paterson grew up in. When my colleagues and I would walk through the projects, the kids would swarm us begging for “sticky badges” (police stickers) and we’d high-five them as they approached. At other times, we’d toss a football, shoot some hoops or kick a soccer ball. The kids always smiled when we’d get back in our patrol vehicles, turn on the emergency lights and chirp the siren and air horn. Many of these kids were dirt poor and living in broken homes, but they were always happy to see us and knew us by name because we made it a point to interact with them and offer hope and stability in their lives.

Two very poignant incidents in my career happened around Christmas. In 2013, I participated in our Shop With a Cop program and was teamed up with a young Black girl who lived in the projects near 14th Street and Monroe. I picked her up in a Tahoe and drove to the event at Spectrum Mall. She was an absolute joy to be with that day as we talked about our families and spent time in Target picking out gifts for her and her family. The event came full circle when I showed up at her apartment on Christmas Day and was met with smiles from everyone, including her mother and siblings who were in the living room enjoying their gifts. The second incident involved a Black family living in South Phoenix who lost everything they had when their grandmother’s house burned a week before Christmas. After hearing about the incident from a firefighter friend, I set the wheels in motion for a PLEA Charities donation. When I showed up to deliver a check, two colleagues who I worked with in 500 were there with monetary donations and items they collected from their squad and other sources. As always, during these interactions, skin color and economic status went out the window. It was raw human emotion — hugs, tears, compassion and gratitude for strangers supporting you in your time of need.

The officers I have had the honor of serving with are as diverse as the areas I worked, but like my fellow soldiers, despite our unique individual characters, we were in it together, working toward a common goal. We had each other’s backs, and if necessary, we were willing to sacrifice our lives for each other. Having each other’s backs also meant keeping each other in check, knowing when to intervene if someone was having an issue with a complainant or a suspect who was getting the best of them, which could lead to a complaint. We worked hard and did our best to solve problems for citizens, but if it did come down to having to make an arrest, we did what it took to get that person into custody. While we preferred to talk people into putting the handcuffs on, there were times we explained we could do it the easy way or the hard way, and if they chose the hard way, they were going to lose — and they did. We made sure our supervisors knew what happened so they could advise the shift lieutenant prior to writing the use-of-force report. We never used excessive force; it was always what was reasonable. Until you’ve had to fight a scrawny 125-pound person for almost five minutes because they were so high on methamphetamine and cocaine that they felt no pain, you’ll never realize how difficult it can be to get someone into custody who is fleeing from the law because of outstanding felony warrants. The same can be said for a suspect with a probation violation who stays hidden in their home with the help of family members, but is stupid enough to leave the house shortly afterward, run from and fight with you after you try to contact them in the parking lot of a nearby shopping center because he knows he is going back to prison if he’s caught.

We never targeted people because of their skin color. We targeted criminal behavior. Many of those exhibiting criminal behavior had been in and out of the judicial system since they were teens and had spent time in prison. Yet they continued to commit crimes, including violent crimes against their families and other members of the community after being released, and some were still on probation or parole. Criminals, especially those on probation or parole, get desperate because they know they’re going back to prison and will do whatever they can to avoid it, even if it means killing a cop.

During my career, 19 of my colleagues have died in the line of duty. Some of their killers were taken into custody alive or without incident, while others were killed. If they were still armed and a threat, they were shot. If they refused to come out of a hiding place after being given numerous opportunities, we sent a K-9 in to get them. If they decided to fight, we used the amount of force necessary to effect the arrest; however, if they surrendered peacefully, there was no reason to use any force other than handcuffing them. This is because we are professionals and can separate the personal emotion of losing a colleague from doing the job we are expected to do. We grieve later on. In that same vein, it disgusts me when activists and politicians try to make an issue of a murder suspect’s arrest by injecting race into the equation and implying that suspects of one race are treated differently than another without providing context to the circumstances of the arrest.

Could relations between the community and the police be better? Is there room for improvement? Can we get back to true community-based policing instead of 21st Century Policing? Can we put aside our personal and political differences and work toward a goal where people can feel safe in their homes and neighborhoods? I personally believe that the men and women who wear a badge and go out there every day to do an increasingly difficult job can and want to, but unfortunately there are politicians and activists, including those who are currently serving on the Phoenix City Council, who are more interested in continuing to push the anti-police agenda rather than find and work toward solutions.

Police unions are once again under fire for allegedly “protecting bad cops” because of the supposed “code of silence” said to exist among police agencies across the nation coupled with the myth of police officers targeting and “hunting down” people of color, which we have heard about in the wake of high-profile use-of-force cases within the past year.

Police labor organizations exist for three primary reasons:

- Negotiations of wages, benefits and working conditions

- Representation in the areas of discipline and grievances

- Legal defense access coverage in the event of a use-of-force or critical incident, including:

˚ In-custody deaths

˚ Officer-involved shootings

Politicians and media outlets often refer to elected police union board members, including myself, as ‘union bosses.’

Where collective bargaining is allowed, unions negotiate what their members can expect in exchange for working for their agency and enter a contract with the employer. Our contract is referred to as a Memorandum of Understanding, or MOU. Basic items of bargaining include wages, benefits and work schedules, but may also include agency, association and officer rights, plus additional compensation for a variety of topics. Under our MOU, overtime, working weekends or other than day shift, standby, call-out, court standby and court overtime, levels of education and training, linguistic skills, uniform, clothing and equipment allowances, off-duty employment, and educational reimbursement are all compensable topics which have been negotiated for over the past 45 years PLEA has been in existence.

PLEA is the certified bargaining unit for all rank-and-file Phoenix police officers and detectives, referred to by the City as “Unit 4.” PLEA, and only PLEA, can represent them with regards to negotiating the MOU, during investigations where misconduct is alleged, and filing grievances when their MOU rights are violated. Dues-paying members have the extra benefits of assistance with filing grievances, representation during the disciplinary process, criminal legal defense coverage for critical incidents and access to attorneys to handle discipline appeals. Unit 4 members who choose not to pay dues or don’t want PLEA to be involved in these types of cases can obtain an attorney of their choice, but PLEA is under no obligation to pay for the attorney or any fees associated with the services provided by that attorney.

Politicians and media outlets often refer to elected police union board members, including myself, as “union bosses.” They equate us to the Mafia Dons, who have had their hands in businesses like trucking, loading and unloading cargo ships, construction and demolition, and trash collection. In the area in New Jersey where my family is originally from, we had union bosses like that. Growing up and into adulthood, I heard stories from my grandparents and my parents about them and the things they did. In July, when I was visiting my parents, my dad told me stories about incidents involving union bosses during his employment as a laborer and manager in the metal can manufacturing industry before he left to open his own business. No police labor organization head would have ever gotten away with what a few of those union bosses did; some of their activities included crimes like extortion, loan sharking, illegal gambling and theft.

As public employees, police officers, including union officials, are subject to following rules and laws set forth by the state, county or municipality they work in. They include administrative regulations, personnel rules and agency work rules like our Operations Orders. Violating the law or any of those rules is considered misconduct, which may result in discipline, up to and including termination, depending on the severity of the violation. Employees represented by a union have Weingarten Rights, meaning if the employer is investigating, and it can result in discipline, the employee has the right to have union representation during that interview. If a work rule violation is sustained, the employee also has the right to a disciplinary hearing and an appeal process if discipline is deemed to be excessive for the level of the violation.

Lately, in the media, I’ve read accounts where several “professional police chiefs” chimed in on the inability of police agencies being able to fire “problem employees.” These are chiefs who left the agency they grew up with and move around from agency to agency, much like some of the very problem employees they talk about. While they may have amassed a wealth of knowledge overseeing various agencies, my own personal opinion is that because they have been in executive management positions for so long, they are far removed from the reality of what the street cop has to deal with every day. While they may claim to know policy, I’d like to know the last time they actually had to interact with a combative suspect while making an arrest. Better yet, when did they last attend and participate in their agency’s in-service training with the rank and file? I’m referring specifically to #8859 firearms drills and qualifications, decision-making in a use-of-force simulator, stress inoculation drills, hands-on arrest/defensive tactics refreshers, driver’s training, and tactical scenarios like traffic stops, building searches, active shooter and mental health crisis hostage situations. My belief is while they may review and approve the training, they don’t actually participate because of their positions.

What many of these chiefs, politicians and members of the public fail to take into consideration when it comes to terminating these so-called problem employees is due process and just cause. Due process simply means if an employer is going to terminate an employee, there are certain procedures that must be followed. Just cause means there are specific standards that must be met before that employee can be terminated.

One thing that PLEA has consistently seen in the 45 years that we have been around representing Phoenix police officers is the subpar quality of some administrative investigations conducted by our Professional Standards Bureau. I think back to my time in the academy as a police recruit where we were told what must be included in any police report: facts. Who, what, when, where, why and how, were the basic elements, and it was equally important to include information that could potentially eliminate or exonerate a suspect’s involvement in the incident. We were also told to keep personal feelings and opinions out of it unless you could substantiate your point with facts. This was all reinforced during field training, and failure to write a detailed, accurate report resulted in plenty of red ink on the draft prior to it being corrected, then finalized. In the courtroom, the result of poor report writing was getting your ass handed to you by a defense attorney as they picked your report apart paragraph by paragraph.

When PSB investigates, the involved employee gets a draft copy to review and is afforded the opportunity to participate in the Investigative Review Process (IRP) within 21 days of reviewing the draft. I’ve lost track of the number of times where PLEA has attended IRPs, and some of the investigators felt like that rookie officer in court because of flaws in the investigation, including blatant exclusion of exculpatory evidence, or inflammatory comments based on opinion. Yet, in many of those cases, PSB refused to make changes to the draft and finalized it.

When officers went to the Disciplinary Review Board, there were members of the board who recognized one-sided investigations and made recommendations that either discipline should be reduced to a lower level, or there shouldn’t be any discipline at all. When a chief moved forward with what PLEA believed was excessive discipline or an unjust termination, the case moved to the Civil Service Board. While there were instances where the board upheld the chief’s recommendation, there were plenty of instances where the board reduced discipline and/or reinstated employees.

Nobody dislikes a bad cop more than a good cop, and throughout our existence, PLEA has walked many employees out the door and helped them surrender their AZ POST Certification. However, when a member’s due process rights were violated, or PLEA believed their discipline was harsh or unwarranted for the level of misconduct, we fought to have that discipline reduced to a level commensurate with the policy violation. As humans, police officers aren’t perfect and will make mistakes. When you have a policy manual of 1,300-plus living, breathing pages that are constantly in flux due to politics, changes in case law, new equipment and technology, updated training and internal processes, officers are bound to violate policy at some point in their career. The difference is whether that violation was deliberate or a mistake of the heart. When an officer deliberately violates policy and doesn’t have a valid or justifiable reason for doing it, then the appropriate discipline should be meted out. If that discipline results in termination, the affected officer can use their appeal rights to see if the decision can be changed.

Absent a dedicated public relations spokesperson, you rarely hear about the philanthropical activities police labor organizations participate in, either through in-house organizations like PLEA Charities or in conjunction with others. PLEA Charities evolved from a long line of charity golf tournaments, starting with one held in honor of fallen Phoenix Officer Patrick Briggs, who was killed in an on-duty motorcycle crash in June of 1990. Over time, the tournament morphed into Tuition Assistance For Police Survivors (TAPS), a scholarship fund for children of Phoenix police officers killed in non-line-of-duty deaths. Once TAPS became self-funded, PLEA Charities became our primary nonprofit, dispersing most of the funds to families of police officers killed or seriously injured in the line of duty. Those funds helped sustain families with covering their expenses until federal benefits were paid out. PLEA Charities’ board decided that community members also needed assistance, so it became a two-pronged approach, providing for police and caring for the community.

Since its inception, PLEA Charities has disbursed over $1.3 million to families of fallen and injured officers and officers enduring family tragedies. My last article mentioned PLEA’s involvement with the Police Cadet Program, and we have also assisted community members who have fallen on hard times. For the past decade, we have facilitated the annual Shop with a Cop program for children in low-income, high-risk families, and until we had to taper things back due to the COVID-19 pandemic, PLEA ran a back-to-school program for schools in low-income neighborhoods, primarily in West and South Phoenix. Students received backpacks with school supplies, and teachers received classroom supplies. The irony is that many of these students live in #8883 city council districts where elected representatives have shown little or no support for the Phoenix Police Department. They are Betty Guardado (District 4), Laura Pastor (District 5) and Carlos Garcia (District 8). Regardless of political differences, PLEA Charities will continue to support less fortunate members of our community to bring hope into their lives when there is despair, and encourage them to be productive members of our society.

Above all, PLEA will continue to advocate for our members, standing up for them when they have been wronged, and having them acknowledge and accept when they were wrong, with the caveat that they learn from their mistake and will do their best moving forward to not let it happen again. For those who take issue with problem employees who allegedly “game the system” to retain their jobs, PLEA suggests that investigators do a better job. That includes abiding by the MOU and not violating the employee rights laid out in it, conducting fair, impartial investigations, based on facts, not conjecture, and understanding that an allegation is just that until it has been proven. PLEA would also suggest that politicians and citizens have a better understanding of the terms, “just cause” and “due process,” because when you take our uniforms off, we are American citizens with the same constitutional rights as every other American, and are just as deserving of those rights, which incidentally, we took an oath to defend against all enemies, foreign and domestic.

This has certainly been an interesting year. The COVID-19 pandemic hit us in March, shutting down the entire country, and in late May, as things in Arizona were starting to open up, the now-infamous video of George Floyd’s arrest went viral and civil unrest broke out in major cities throughout the country, including Phoenix. While I agree the video looks horrible, I will reserve judgment because I do not have all the facts and I will let due process run its course.

There are many ways calls for service can be reduced without taking money out of police budgets. However, other programs must continue.

The latest mantra to come from the progressive left is “defund the police,” which can be taken in different contexts: reduce public safety budgets, shift police funding to other community programs or, the most radical, completely eliminate police departments. After being part of the law enforcement profession for over 29 years, I can actually buy in to some of these ideas, and I know firsthand the City of Phoenix has been a pioneer in reducing public safety budgets.

- After 2008’s Great Recession, the City of Phoenix didn’t hire police officers for over six years.

- During that time, the City deferred paying pension debt.

- All City employees took voluntary wage and benefit cuts to “help out” the city and community so no employees were laid off and parks, pools, libraries and senior centers didn’t have to close.

- For police officers:

- From 2010 to 2012, there was a 1% wage cut and 16 mandatory furlough hours.

- From 2012 to 2014, the 1% wage concession was restored.

- From 2014 to 2016, uniform allowance was reduced by 50% and there were 12 unpaid holiday hours in the first year of the contract. In the second year of the contract, concessions continued and additional unpaid holidays were added for a total of 32 unpaid holiday hours.

- Full concessions were finally restored in 2018, and in 2019 topped-out officers received their first raise in 12 years.

- The Phoenix Police Department has yet to hit the City Manager’s 2018 goal of having 3,125 total sworn officers, 263 fewer than in 2008 when the city had a smaller population and geographical footprint.

There are many ways calls for service can be reduced without taking money out of police budgets. However, other programs must continue, as they foster positive police–community interaction and influence those willing to participate.

Community members are recommending there should be more mental health services, and I would strongly agree. Mental health is not a police matter, and instead of relying on police officers who have been Crisis Intervention Trained to respond, it should be done by mental health professionals. Then if things escalate to the point of serious injury or bodily harm, that might be the time for police intervention. Arizona Revised Statute 36-525 tasks peace officers with apprehension and transportation of people who are court-ordered to be brought into a facility for mental health evaluations. PLEA, through the Arizona Police Association, has tried to have this legislation changed, but the mental health industry’s lobby has been able to convince legislators that this is a police function, and we are still saddled with the task. I believe it is a huge liability, despite the increased use of CIT teams in “soft” uniforms. Mental health pickups have turned into officer-involved shootings after the subject of the call became violent and attacked the officers, leaving them with no response option other than lethal force. These cases have resulted in lawsuits costing taxpayers millions of dollars for doing something that should have been left to medical personnel. Police vehicle prisoner compartments are designed to restrain and contain people, including violent felons, who have been taken into custody for transport to a police facility or jail, and they are not conducive to transporting individuals in mental distress. Ambulances and medical transport vans are specifically designed for this task, and ambulances are manned by trained EMTs who can immediately address any medical condition that may arise during transport. If a patient dies while a police officer is transporting them, the officer becomes the subject of an in-custody death investigation, where, again, an agency can be sued.

Homelessness is a complex social issue; however, the effects of homelessness often become police matters, specifically when they involve criminal acts. Most #9657 street cops who regularly deal with the homeless will tell you many of them suffer from mental illness and substance abuse. For some of them, it is purely a lifestyle choice — they would rather live on the street than be in a structured program designed to help them, because they don’t like following rules.

Minor traffic collisions involving only property damage should not be a police matter. However, because the automobile insurance industry in Arizona has powerful lobbyists, police officers are essentially acting as insurance adjusters. The Arizona Police Association had to fight tooth and nail to get the damage threshold raised to $1,000 from $500 to differentiate between reportable and non-reportable trafficway collisions. As an example, something as simple as paint transfer between two vehicles making contact, where there is no structural damage, can cost thousands of dollars to repair. Absent aggravating factors like serious injuries or impaired driving, as more insurance companies offer apps allowing customers to take photos of the involved parties’ information and damage, then submit a claim, there is no need to have the police involved in what is essentially a civil matter.

Community outreach and youth programs have bridged the gap between police and residents in neighborhoods all over the city, particularly in low-income and high-crime neighborhoods. For those of us who became cops in the 1990s, community-based policing was literally pounded into our heads in the academy, and during field training it was all about beat accountability. Unfortunately, in Phoenix, beat accountability is largely a concept of the past, thanks to the constant reallocation of manpower. We simply don’t have enough patrol resources for a city of our size and have to be continually reactive instead of being proactive. We also don’t have sufficient investigative resources to follow up on the cases generated by patrol officers. There was a time when cops knew the people in their beat and had a finger on the pulse of what was going on. That includes residents, business owners and even the bad guys. If something particular happened or there was a crime trend, most of the time, the beat cop knew who or what was responsible due to positive relationships garnered while working a specific squad or beat area. In turn, they shared that information with squadmates, other patrol squads who covered the same area,

NET teams and detectives. Now, the beat cop is nothing but a call sign, a pinball bouncing from call to call with little time for community interaction and no ability to focus on problem locations to identify the causes of and find ways to reduce crime and calls for service.

The current Phoenix Police Cadet program invites the youth of the community to learn about police careers. It evolved from the Explorer Scout program, a 42-year-old program proven to be a successful recruiting tool for highly qualified recruits. Over the years, it has trained, mentored and coached interested young adults for those positions. A study done in 2001–2002 showed 14% of Explorers from Post 2906 became Phoenix police officers. Current 2019–2020 statistics are as follows:

- Nine have entered the military.

- Eight have secured employment with the Phoenix Police Department.

- Gender participation is 60% female and 40% male.

- The 2019 ethnic breakdown was as follows:

- 63% Hispanic

- 32% Caucasian

- 3% African American

- 1% Asian and Pacific Islander

- 1% Multi-ethnicity

Statistics from a decade ago show the program was 70% minority (Hispanic) and 34% female, and some of those young adults came from families who were less than supportive of their decision to consider a law enforcement career. In 2010, when the City trimmed the police department budget, it was one of the first programs to go, despite the positive outcome of the program and the thousands of hours in community service provided by the participants. PLEA recognized the value of the program and held fundraiser cookouts. PLEA Charities also started a scholarship program for participants who were going on to secondary education, which is still helping eligible cadets. In addition, the Phoenix Police Department Athletic Club helped out by donating proceeds from the Phoenix Combat Classic shooting competition.

Lately, we have seen increased pressure by community activists to eliminate police officers from school campuses. Post-Sandy Hook, you couldn’t find enough police officers to put in schools, and for the most part, the School Resource Officer program has been effective, not only in educating students but when officers are allowed to do their jobs and take action when crimes have occurred. However, we continually see negative press where SROs have been directed to do the dirty work district administrators and principals refuse to, yet the schools are quick to file complaints against their assigned SRO. Eliminating small problems before they become larger ones is one way these programs are effective. Students form positive relationships with the SRO, in turn earning mutual respect and learning how to be a productive member of society who is willing to follow the rules and effect positive change on their own.

In order to have a professional police department, you must recruit the best-qualified candidates for the position and provide them with a competitive wage and benefits package. Then, you must provide them with the best equipment, technology and training that is available and continually update all of it. This specifically applies to training, and that training should be hands-on for perishable skills like driving, defensive/arrest tactics and firearms. The downside to having a police department like this is that it costs money — money that politicians aren’t willing to spend and that community activists want to take away.