As I’m typing away on my keyboard, I’ve got a smile on my face, a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye as I realize that this will be my last official writing for an organization I’ve been part of for the past 26 years. As a child growing up, I would never have imagined that half a century later, I’d be 2,500 miles away from the place I envisioned living my life, and working in a profession that was a playtime activity based on Adam-12. Events that occurred in my life and the lives of family members led to an Arizona vacation, then a decision to leave New Jersey and move to Phoenix, which paved the way for me to become a Phoenix police officer.

As I’m typing away on my keyboard, I’ve got a smile on my face, a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye as I realize that this will be my last official writing for an organization I’ve been part of for the past 26 years. As a child growing up, I would never have imagined that half a century later, I’d be 2,500 miles away from the place I envisioned living my life, and working in a profession that was a playtime activity based on Adam-12. Events that occurred in my life and the lives of family members led to an Arizona vacation, then a decision to leave New Jersey and move to Phoenix, which paved the way for me to become a Phoenix police officer.

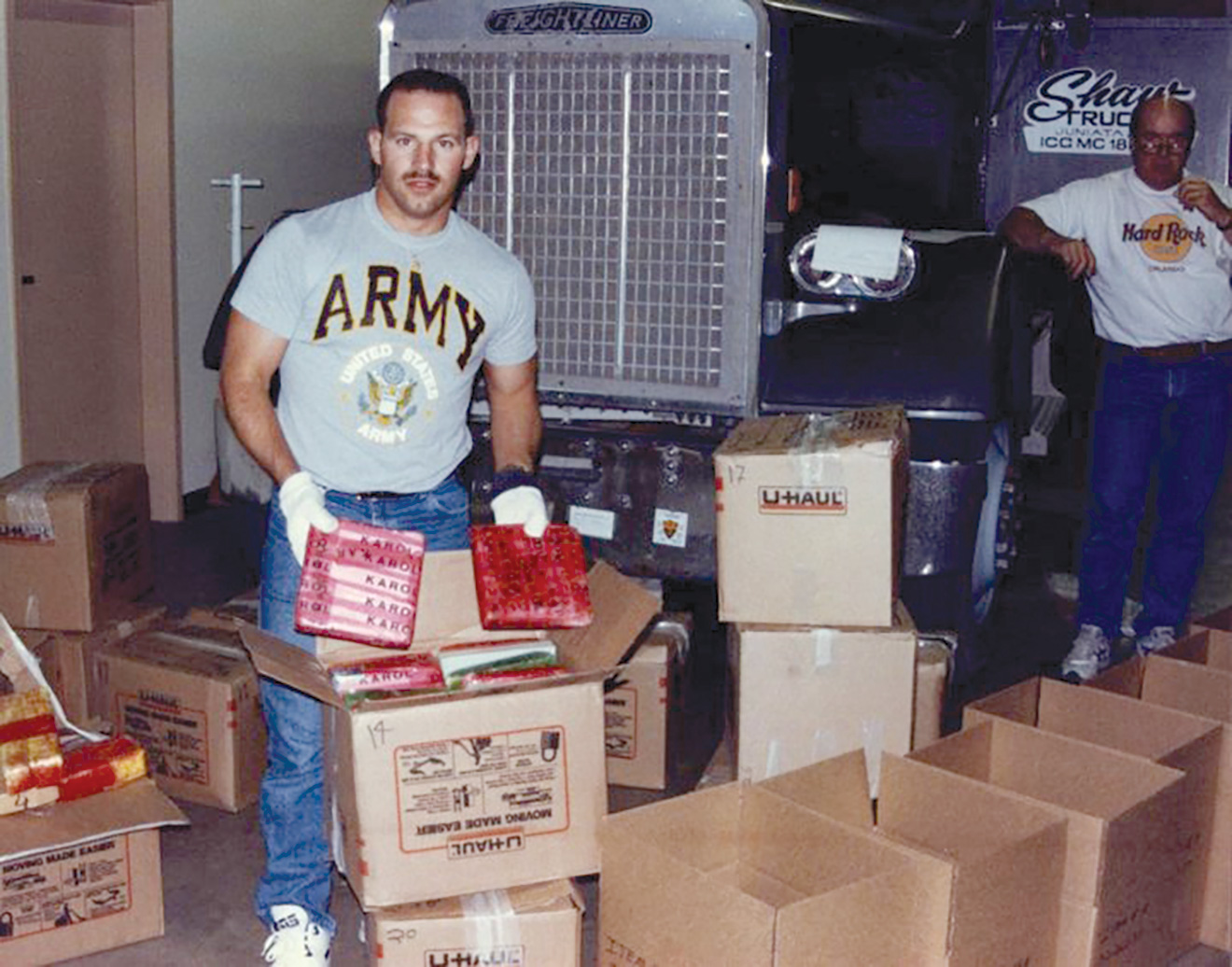

After visiting Arizona twice in 1988, I tested for Scottsdale in the spring of 1989. I completed my oral board and never heard back from them. Arizona became my new home that fall, and a year later, in 1990, my Military Police unit was activated for Desert Shield, which became Desert Storm. The deployment changed my life course and reaffirmed my goal of becoming a police officer. In November 1991, I finally had the opportunity to test for the Phoenix Police Department, which was considered the premier agency in Arizona. Instead of attending my 10-year high school reunion in New Jersey, I took the written test with hundreds of others at the old Civic Plaza and proceeded to the Academy for my physical fitness test. The MCSO deputy who scored my sit-ups said I did not complete the required number. Since I was on active military duty, my first thought was to challenge him, because I worked out daily and made it a point to be able to pass the PT test with well above the minimum reps for both push-ups and sit-ups. However, the soldier in me knew a challenge could work against me, so I retested in January 1992, passing with no issues. Then, Phoenix had a hiring freeze, so I tested with Chandler and the Pima County Sheriff’s Office, only to be put on waiting lists.

It has been an honor and privilege to serve the membership over the past 20 years, working to right wrongs and fighting the good fight.

By September 1992, Phoenix began hiring again, but I opted to use my GI Bill benefits to attend college. My thought process was that secondary education would make me more competitive in the hiring process. In the spring of 1994, I tested again and was hired in late September. I started the Academy on October 3, 1994, with Class 265, graduated on January 13, 1995, and was assigned to 500 to start the FTO program. 500 would be home for most of my career; I spent my first seven and a half years on second shift, including four and a half years on an FTO squad. During my time as an FTO, former PLEA President Ken Crane and I worked as partners, and he persuaded me to get involved with PLEA as a representative. The furthest thing from my mind when I became a cop was any aspiration of being a labor representative; however, as it has been said, “Everything has a reason for happening,” and happen it did. During that same time period, another life event occurred: I met my wife, Dena. When we started dating, she was a single mother, and when we decided we were going to get married, I opted to go to third shift to spend more time with her and my daughter and son, which is where I spent the next nine years of my career. It’s enough of a challenge raising a family when you’re a cop working holidays, getting home late due to holdover and missing family events because of shift conflicts or the inability to get time off. However, the move allowed me to attend recitals, concerts and other school events, T-ball and soccer games, and scouting events. I’m grateful for that family time we shared.

In 2009 I was appointed to the PLEA Board to fill a vacancy, then ran for and was elected to a trustee position. I became chair of the Board within a year, and in 2011, former PLEA President Joe Clure asked me to run for secretary, which I did. That August, I moved into a full-time release position in the PLEA Office. When you combine the challenges of being a cop and raising a family with being a police labor representative, it’s a whole different game when you are actively involved in the organization, and that compounds when you become a Board member. Your cellphone becomes an appendage, with what can seem like nonstop calls, text messages and emails coming in at all hours, regardless of whether you’re working, on your days off or on vacation in the mountains. Why is that? It’s because you are a resource for people seeking your guidance and wisdom in their moment of need. It also means callouts in the middle of the night or on weekends and days off while taking standby.

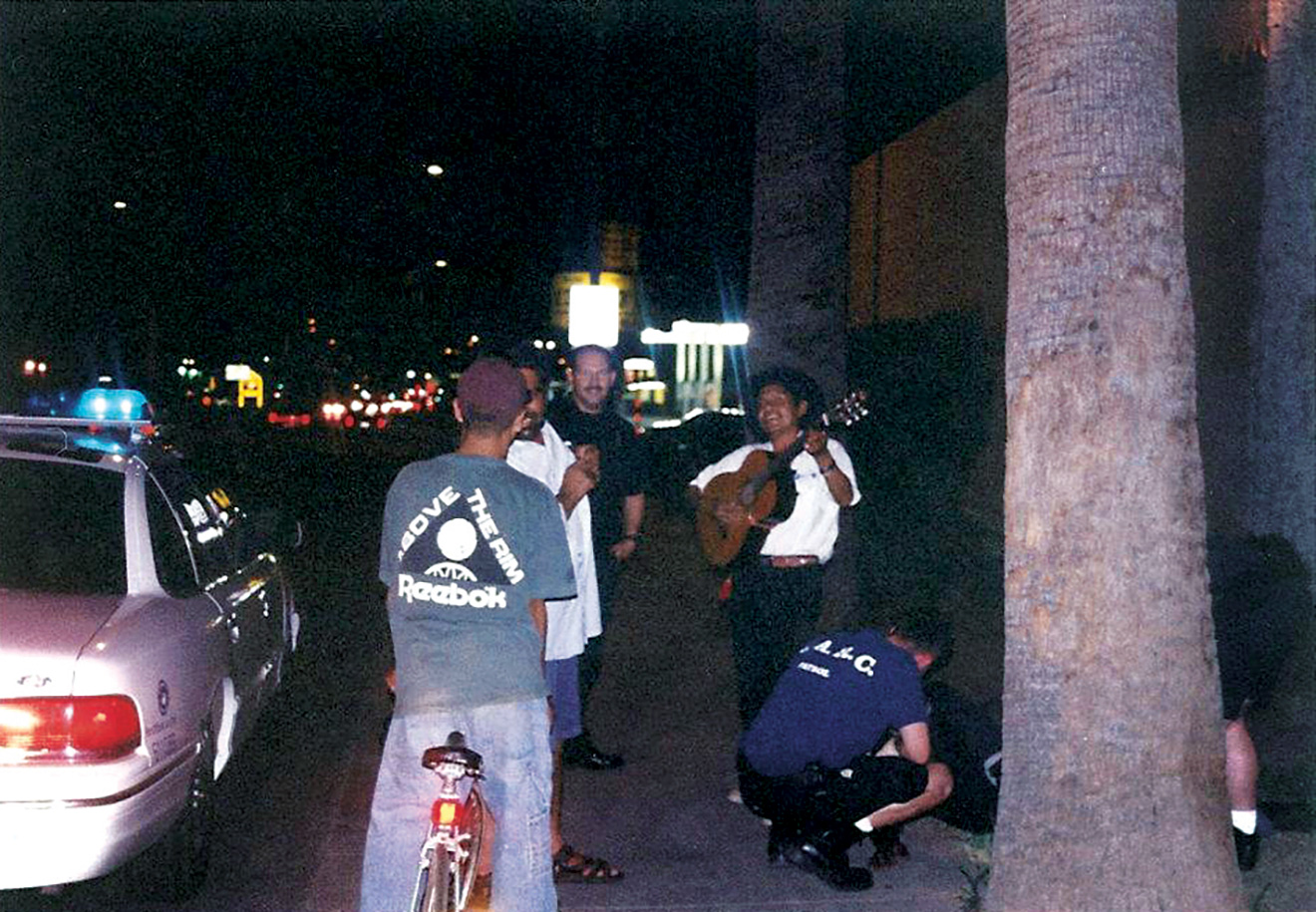

In June 2012, I spent two weeks assigned to 600 after the first Goldwater injunction; then, in May 2013, I went back to 500 after the second one. After almost a year and a half, I opted to go to 700 in the 2014 rebid and stayed there for nearly two years, until the Arizona Supreme Court overturned the Goldwater injunction in September 2016 and I returned to PLEA. During my time in 700, I worked the former 52 and 53 areas, where I had cut my teeth and spent most of my career as a beat cop. I felt comfortable and confident working in my old backyard. The most challenging three years and four months of my stint as a PLEA Board member were during the Goldwater injunction, because I remained on a Patrol squad and did not make it back to the office. In addition to working 10-hour-plus shifts, I was handling PLEA business prior to and after my shift, as well as on my days off. Having said that, if I didn’t have a full-time release position, I would have opted to stay in Patrol, because it’s what I loved doing, even though it has drastically changed within the past few years. Despite the challenges during those years, there were some good times, and I got to push my limits as a street cop thanks to another partner, Kevin Wilson, who, like me, became a PLEA rep and Board member. We got into several potentially dangerous situations during the time we worked and rode together, but we made numerous felony arrests, including some that were tied to very complex cases. We did not make any excuses for pushing the limits; that’s what happens when you’re a street cop at heart and love the thrill of the hunt and chase.

I never had the desire to promote. Between my deployment to Saudi Arabia during Desert Storm and my active-duty assignment on the Task Force, I had my fill of supervising, including a few problem children who taxed my patience. During my time on the Department, I worked for a number of good supervisors, but I also worked for my share of bad ones. I saw the flaws of a system that promoted test-takers versus leaders and those with the solid tactical base of a street cop. Granted, I could have become part of the solution by promoting, but for me, it was more challenging and rewarding to become part of the solution as a PLEA rep. That gave me the ability to hold both bad officers and bad supervisors accountable for their actions, whether it was a simple mistake of the heart or blatant misconduct. Bad officers got walked out the door, while officers who made mistakes, or were alleged to have made mistakes but didn’t, were vilified at Use of Force and Disciplinary Review Boards or meetings with the Police Chief. Bad supervisors or supervisors who bullied their troops were also dealt with, while good supervisors who supported their troops, sometimes against the will of their superiors, were rewarded. Speaking of rewarding, going head-to-head and taking to task a bullheaded, overzealous former “Chief of Police” was one of the more rewarding things I did as a rep. As I always tried to explain to supervisors and managers who were willing to listen, it wasn’t personal; it was business, and it shouldn’t interfere with working together for a common cause and goal, which we signed up for when we became cops.

When I was hired, Phoenix was the police department everyone wanted to work for but couldn’t. Hiring standards were well above AZ POST minimum; the Academy had a paramilitary format that challenged us and weeded out those who couldn’t meet standards. Not everyone made it through the FTO program, and not everyone who managed to go solo was able to keep up with the pace afterward and complete probation. While we worked hard and consistently got our asses handed to us in terms of call volume combined with holdover on the weekends due to multiple violent crime scenes, we had fun doing it. We were still allowed to do police work, and it involved going after people who committed crimes and putting them in jail, sometimes after a vehicle or foot pursuit. Pushing the limits to the edge was common and, thankfully, most of the supervisors I worked for and under were street cops at heart and did what they needed to do to make sure overzealous commanders didn’t come after us.

While police work itself has remained relatively unchanged, technology has affected it positively and negatively. When I came on, our issued Glocks did not have weapon light rails, and our gun belts, holsters and accessories were heavy, synthetic leather. Most of us carried a rechargeable Maglite or Streamlight that doubled as an impact weapon, and while some of us were designated as shotgun operators, we didn’t have Tasers or patrol rifles. Pagers were common and some of us had cellphones. Our patrol vehicles were Chevrolet Caprices, but they had halogen rotator emergency lighting and no reflective markings. They did have Mobile Data Terminals, which allowed us to receive and disposition calls, run records checks on people and vehicles, and complete false alarm and field interrogation cards; however, they had less functionality than the most basic smartphones of today. We either handwrote our reports and turned them in at the front desk, or dictated them to a live secretary or a recorder called the Voicewriter for eventual transcription and entry into PACE, which was much easier to navigate than RMS. Booking paperwork was filled out by hand and could be done on the hood or trunk of a patrol car at the scene before heading to the “Horseshoe” at the Madison Street Jail, where it would be reviewed by a police assistant before you turned your prisoner over to MSCO personnel. Over the years, technology made some processes easier while hamstringing and lengthening others.

Caprices gave way to Ford Crown Victorias and vehicle-mounted laptops that were difficult, if nearly impossible, to remove to get the intended function out of them. Every marked patrol vehicle had a less-lethal stun bag shotgun, and each squad had designated Taser operators until everyone in Patrol was issued a Taser. 2001 marked the implementation of the Patrol Rifle Program, full-sized 20-inch-barrel “politically correct” Colt AR15 HBAR Sporters. It would take a few years for common sense to work its way into the program, upgrading to Colt LE6920 Carbines with 16-inch barrels and collapsible stocks. In 2005, we tested our first Tahoe with much-improved emergency lighting and internal gun racks. As the Crown Victoria was slowly phased out, Tahoes were integrated into the fleet. We used the Chevy Impala purely for cost savings and to get the fleet modernized. Gun racks were moved to the front of the Tahoes for easy access, while laptops slowly improved. Eventually, we had console-mounted printers and scanners for use in conjunction with TRACS, which is how we wrote crash reports and issued citations and exchange cards. In 2013, after over a decade of testing and evaluating various emergency lighting packages, we finally had 100% LED emergency lighting on our Tahoes. We continued to improve the interior setups, eventually convinced City bean-counters that an all-Tahoe fleet would save money in the long run based on vehicle life cycle costs, and stopped purchasing Impalas and the reintroduced Caprice. RMS replaced PACE, and many of us still believe PACE was a much better system despite it living on borrowed time. Some of us still affirm that a fraction of the money dumped into RMS could have prolonged PACE, but the City and Department hate to admit when they’re wrong, as they’ve been with the entire RMS fiasco. Body-worn cameras went citywide from a pilot program in Maryvale and continue to prove what we knew before we had them: Phoenix police officers are professional, do a good job and use reasonable force when necessary to conduct our mission. They also show that we deal with violent individuals on a more frequent basis than we ever have and resort to lethal force when there are no other options available, despite the rhetoric heard from anti-police activists and members of our City Council.

Caprices gave way to Ford Crown Victorias and vehicle-mounted laptops that were difficult, if nearly impossible, to remove to get the intended function out of them. Every marked patrol vehicle had a less-lethal stun bag shotgun, and each squad had designated Taser operators until everyone in Patrol was issued a Taser. 2001 marked the implementation of the Patrol Rifle Program, full-sized 20-inch-barrel “politically correct” Colt AR15 HBAR Sporters. It would take a few years for common sense to work its way into the program, upgrading to Colt LE6920 Carbines with 16-inch barrels and collapsible stocks. In 2005, we tested our first Tahoe with much-improved emergency lighting and internal gun racks. As the Crown Victoria was slowly phased out, Tahoes were integrated into the fleet. We used the Chevy Impala purely for cost savings and to get the fleet modernized. Gun racks were moved to the front of the Tahoes for easy access, while laptops slowly improved. Eventually, we had console-mounted printers and scanners for use in conjunction with TRACS, which is how we wrote crash reports and issued citations and exchange cards. In 2013, after over a decade of testing and evaluating various emergency lighting packages, we finally had 100% LED emergency lighting on our Tahoes. We continued to improve the interior setups, eventually convinced City bean-counters that an all-Tahoe fleet would save money in the long run based on vehicle life cycle costs, and stopped purchasing Impalas and the reintroduced Caprice. RMS replaced PACE, and many of us still believe PACE was a much better system despite it living on borrowed time. Some of us still affirm that a fraction of the money dumped into RMS could have prolonged PACE, but the City and Department hate to admit when they’re wrong, as they’ve been with the entire RMS fiasco. Body-worn cameras went citywide from a pilot program in Maryvale and continue to prove what we knew before we had them: Phoenix police officers are professional, do a good job and use reasonable force when necessary to conduct our mission. They also show that we deal with violent individuals on a more frequent basis than we ever have and resort to lethal force when there are no other options available, despite the rhetoric heard from anti-police activists and members of our City Council.

I have many people to acknowledge and thank for what I have achieved. First and foremost, I give thanks to God for looking out for me every step of the way during this amazing journey, but there are countless others, many of whom I’ve alluded to in the articles I’ve written over the years. From childhood into adulthood, there were many cops who left impressions on me. They include cops I encountered growing up, the beat cops who’d stop in at my dad’s shop and a neighbor who was a patrol sergeant on our township police department. There were other cops from various agencies I met and worked with after my enlistment in the Army National Guard and service in two different Military Police units, and I met others during training and activations. During my three-plus years of active duty on the Arizona National Guard’s Joint Counter-Narcotics Task Force, I met more cops and federal agents. Those experiences and the knowledge I gained firmly set the wheels in motion for a major life and career change. As I was laying the groundwork and contemplating that change and the decision to become a police officer, there was unconditional support from my immediate and extended family and friends. My parents, sisters, grandmothers, aunts, uncles and cousins were there for me through the entire process and beyond. Longtime family friends and personal friends, including some from high school, others I met afterward, my “Whiskey Bravos” and other Army buddies, some of whom served or continue to serve in law enforcement, have all been a part of my support network. I met my wife when I had five years on the job and she has been there through thick and thin. She and my daughter and son have always understood the complexity of the job and supported and encouraged me during the best and worst times of my career since they’ve been a part of my life.

The past 26 years have been awesome, and I’m glad I had the opportunity to be part of a great law enforcement agency before it was dismantled by spineless politicians and managers who lost touch with their street cop roots. I always tried to do the right thing for the members of the community whom I ultimately served, and I had the honor and privilege to work with some amazing cops over those years — some who are still with us, some who left this Earth too soon, others who have retired, and still others who are doing bigger and better things at other agencies because of the skills they gained working for Phoenix. It has been an honor and privilege to serve the membership over the past 20 years, working to right wrongs and fighting the good fight when necessary. Having said that, it also has been an honor and a privilege to have served as an elected Board member under four different PLEA presidents over the past 12 years. While we may have had philosophical differences at times, we all worked together for the greater good of the membership. Farewell, my friends and colleagues; it has been a helluva ride! 6024 is 10-7!