Articles

Archive of articles posted to the website.

While COVID-19 has understandably been at the center of the dialogue concerning officer health and wellness throughout the past year, it’s important to remember the devastating effects cancer continues to have on law enforcement officers around the country. First responders have a significantly higher chance of succumbing to cancer compared to the general population due to high stress, toxic exposures and other factors. For this reason, I want to inform our members about the Vincere Cancer Center, which offers a first responder screening program that has helped countless police officers since it was established in 2018.

While COVID-19 has understandably been at the center of the dialogue concerning officer health and wellness throughout the past year, it’s important to remember the devastating effects cancer continues to have on law enforcement officers around the country. First responders have a significantly higher chance of succumbing to cancer compared to the general population due to high stress, toxic exposures and other factors. For this reason, I want to inform our members about the Vincere Cancer Center, which offers a first responder screening program that has helped countless police officers since it was established in 2018.

The best part is that the Vincere Cancer Center offers a thorough screening, complete with a body scan MRI and lab work, for free.

The program was created by Dr. Vershalee Shukla after research she conducted showed that cancer diagnoses had reached an epidemic level among first responders. As a result, Dr. Shukla and her team of doctors have made it their mission to help our members overcome the fear and uncertainty that comes from a possible cancer diagnosis. The best part is that the Vincere Cancer Center offers a thorough screening, complete with a body scan MRI, CT scan and lab work, for free (must be enrolled in an active City health insurance plan). This free screening also allows members to meet with Dr. Shukla and her team to ensure all questions and concerns are answered. All you need to do is visit vincerecancer.com/screening to fill out a short form. Within one business day, you’ll be contacted about setting up an appointment. (Please note, this is currently not available to our retired members due to agreements between Vincere Cancer Center and the City of Phoenix.)

Of course, if a more comprehensive screening is needed afterward or you are referred out to a specialist, normal co-pays would apply. Your health is their absolute top priority, and these are some of the best medical professionals in the state.

This incredible program is a huge benefit to the men and women of the Department, so please don’t hesitate to get in touch with the Vincere Cancer Center today at (480) 306-5390 or by visiting vincerecancer.com. The center is located in Scottsdale at 7469 E. Monte Cristo Ave.

Even if you feel perfectly healthy and believe a cancer diagnosis could never happen to you, do your loved ones a favor by taking this opportunity to schedule a free appointment. With most any medical issue, the earlier it is detected, the better the chance of beating it. As always, if you have any questions or comments, I am available at the PLEA Office via phone or email at dkriplean@azplea.com.

PLEA Scores a Hole-in-One at Annual Event

On a recent sunny Saturday afternoon, 300 PLEA members teed off at the annual Fallen Officer Memorial Golf Classic at Wigwam Resort & Spa in Litchfield Park. The event, which raised much-needed funds for PLEA Charities, was a massive success and a welcome return to form after COVID-19 and election conflicts forced the tournament to be postponed last year.

On a recent sunny Saturday afternoon, 300 PLEA members teed off at the annual Fallen Officer Memorial Golf Classic at Wigwam Resort & Spa in Litchfield Park. The event, which raised much-needed funds for PLEA Charities, was a massive success and a welcome return to form after COVID-19 and election conflicts forced the tournament to be postponed last year.

The full-capacity event featured a new and exciting tee box and putting events, fun prizes and a catered lunch. Rudy Peru and his three sons once again brought their A-games by winning the tournament for the second straight time. “We put the ball closer to the pin more frequently and had no bogeys,” Peru says. “It always makes it nice and easy having most shots close to the hole and good putts.”

The team’s strong day on the course was highlighted by “scoring an eagle on a par-4,” says Peru, whose first shot that hole landed just seven feet from the cup.

While the victory was certainly sweet, the best part for Peru was spending time with his sons and contributing to a great cause. “I have attended this tournament every year since I can remember, and I really enjoy the time I get to spend with my three boys — time spent with my sons is most important,” Peru says. “The event also brings people together and builds camaraderie. It is a great event that not only honors fallen officers but brings in money for PLEA Charities.”

PLEA Charities is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that strives to promote the positive image of law enforcement, assist officers and their families in need and contribute to community members and causes. In a time when law enforcement has increasingly been under attack, Peru says being able to give back shows PLEA’s commitment to working toward positive change and building relationships with the community.

“I feel that law enforcement is not being shown in the best light at this time,” he explains. “This event is a good way to show the positive influence police have on the community, and anything we can do to build relationships is awesome. Thank you to the vendors and sponsors for showing support. Everyone who attends the golf tournament always has a good time.”

PLEA would like to thank all the sponsors, golfers and volunteers for holding strong throughout this difficult last year and making this year’s tournament one to remember. We can’t wait to see everyone next year!

The Supreme Court has held that the Fourth Amendment prohibits law enforcement officers from using excessive force when apprehending a suspect or making an arrest. Under 42 U.S.C. §1983 such a violation means that officers who use excessive force are subject to civil liability. Qualified immunity provides protection from civil lawsuits for law enforcement officers and other public officials. The doctrine recognizes the need to protect officials who are required to exercise their discretion and the related public interest in encouraging the vigorous exercise of official authority. But, qualified immunity is not absolute immunity and there are situations in which a public official can be held accountable for constitutional violations in civil court. “[Q]ualified immunity protects ‘all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.” Mullenix v. Luna, ___U.S.___, 136 S. Ct. 305 (2015) (quoting Malley v. Briggs, 475 U.S. 355, 106 S. Ct. 1092, (1986)).

The longstanding two-part test the Courts use to determine whether qualified immunity applies requires an analysis of: (1) Did the officer violate a constitutional right? and (2) Did the officer know that their actions violated a “clearly established right”?

While the doctrine of qualified immunity has not been codified by Congress in legislation, the Supreme Court has revisited the issue in several cases over the years and has previously signaled endorsement of the public officials’ liability shield. In addition to the recognized common law doctrine, qualified immunity has been codified by the Arizona legislature in A.R.S. §12-820.02 and A.R.S. §13-413 (no civil liability for justified conduct).

Kisela v. Hughes — Expanding Entitlement to Qualified Immunity in Use of Force Cases

On April 2, 2018, in Kisela v. Hughes, 584 U.S. ___, the United States Supreme Court overturned a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision in favor of a woman who had been shot and wounded by a law enforcement officer in Tucson, Arizona. In doing so, the Court held that the officer was entitled to qualified immunity because the incident was far from an obvious case in which any competent officer would have known that it violated the Fourth Amendment.

Factual Background

In May 2010, three officers responded to a 911 report that a woman was acting erratically and hacking at a tree with a large kitchen knife. Upon arrival, the officers observed a woman standing next to a car in the driveway of a nearby home. The officers were separated from the woman by a chain link fence. Another woman exited the home carrying a large knife at her side. This woman, later identified as Amy Hughes, matched the description provided by the 911 caller. Hughes approached the woman in the driveway and stopped approximately six feet away.

At this point, the officers drew their guns and twice ordered Hughes to drop the knife. Although Hughes appeared calm, she did neither acknowledge the officers’ presence nor dropped the knife. Without additional warning, one officer dropped to the ground and shot Hughes four times through the fence. The entire incident lasted less than a minute.

Hughes survived the shooting and sued the officer who shot her, alleging a violation of her civil rights. A federal district court ruled for the officer, but the Ninth Circuit reversed, holding, first, that the record was sufficient to establish that the officer violated Hughes’s Fourth Amendment rights and, second, that the officer was not entitled to qualified immunity because the Fourth Amendment violation was obvious and clearly established by previous, similar court cases.

The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit without deciding whether the officer had violated the Fourth Amendment. Instead, it held that even assuming the officer used excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment, he was entitled to qualified immunity.

The Court explained that “[q]ualified immunity attaches when an official’s conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known” and cautioned against lower courts defining “clearly established rights” too generally. For a right to be clearly established, existing precedent must have placed the constitutional issue beyond debate. In the context of use of force cases, “[a]n officer ‘cannot be said to have violated a clearly established right unless the right’s contours were sufficiently definite that any reasonable official in the defendant’s shoes would have understood that he was violating it.” Thus, “police officers are entitled to qualified immunity unless existing precedent ‘squarely governs’ the specific facts at issue.” The Court found that the Ninth Circuit had failed to apply this portion of the standard correctly.

The Court considered the standard in light of the following facts:

- The officer had only a few seconds to assess the potential threat.

- The officer was confronted with a woman armed with a large knife who was reported to have been behaving erratically.

- Hughes was only feet away from another individual and failed to acknowledge two separate commands to drop the knife.

- The officer claimed to have shot Hughes because he believed she posed an immediate threat to the woman standing next to her.

- The other two officers on scene reported that they also believed Hughes was a threat.

Given those facts and the lack of precedent with a sufficiently similar fact pattern, the Court concluded that this was “far from an obvious case in which any competent officer would have known that shooting Hughes to protect [the third party] would violate the Fourth Amendment.” Accordingly, the Court held that the officer was entitled to qualified immunity and reversed the Ninth Circuit’s decision.

Dissent

It should be noted that not all justices agreed with the majority’s decision to reverse. Justice Sotomayor authored a strong dissent, joined by Justice Ginsburg, asserting that the ruling “is not just wrong on the law; it also sends an alarming signal to law enforcement officers and the public” that officers “can shoot first and think later.” Justice Sotomayor’s disagreement centered on the “clearly established” standard. In her view, the majority placed too much emphasis on there being a factually identical case. Rather, she wrote, “[i]t is enough that governing law places ‘the constitutionality of the officer’s conduct beyond debate.’ Because, taking the facts in the light most favorable to Hughes, it is ‘beyond debate’ that [the officer]’s use of deadly force was objectively unreasonable, he was not entitled to summary judgment on the basis of qualified immunity.”

Conclusion

So what does this decision mean for you? Kisela provides additional support for the principle that law enforcement officers must have knowledge that their actions would violate the Fourth Amendment before they can be held liable for a use of force incident. Unless a factually similar case #10032 existing before a use of force incident demonstrates that your actions were clearly unconstitutional, you would likely be entitled to qualified immunity. This ruling, thus, will likely be helpful in defending officers sued civilly for uses of force. This ruling does not, however, affect the Department’s ability to discipline you for any policy violations arising out of a use of force incident. Thus, it remains imperative that you contact PLEA if you are involved in a use of force incident. PLEA representatives and the attorneys PLEA provides will ensure that you understand all possible criminal, civil, and administrative implications.

As always, if you wish to discuss this case or any other matter affecting your employment, please feel free to contact PLEA’s attorneys at Napier, Coury & Baillie, P.C.: (602) 248-9107 or napierlawfirm.com

The Arizona State Legislature began its 55th session on January 11. Here are some of the law-enforcement-related bills that have been introduced and are being monitored by our partners at the Arizona Police Association (APA).

Support

SB 1396: PSPRS; survivor benefits: Would amend the guideline for a surviving spouse’s pension from the Public Safety Personnel Retirement System, currently set at 40% of the deceased member’s average monthly salary, to that amount or four‑fifths of what the deceased member’s pension would have been on the date of death had the member been retired, whichever is greater.

HB 2295: Law enforcement officers; database; rules: Would require that a prosecuting agency send a notice to a law enforcement officer at least 10 days before considering placing them in a Rule 15.1 database (aka Brady list), and would allow them to appeal being placed in the database. It would also forbid an agency from using an officer’s placement in a Rule 15.1 database as the sole reason for demoting, suspending or firing them.

HB 2348: Failure to return vehicle; offence; repeal: Would repeal Section 13‑1813 of the Arizona Revised Statutes, which classifies as theft the unlawful failure to return a motor vehicle subject to a security interest.

HB 2462: Civilian review board members; training: Would require that, before a person becomes a member of a civilian review board that reviews the actions of peace officers, they must satisfactorily complete a community college police academy and at least 20 hours of virtual law enforcement training.

HB 2504: Appropriations; DPS; salary increase: Would appropriate money from the state’s general fund for a 10% salary increase for all Department of Public Safety employees.

HB 2505: Appropriations; corrections officers; salary increase: Would appropriate money from the state’s general fund for a 10% salary increase for Department of Corrections officers and investigators, as well as for Department of Juvenile Corrections officers.

HB 2567: Peace officers; investigator membership requirements: Would require that at least two-thirds of the voting membership of any government committee, board or other entity that investigates law enforcement misconduct or recommends discipline be made up of POST-certified law enforcement officers from the same agency as the officer who is subject to the investigation.

HB 2763: County officials; practice of law: Would end the prohibition on county sheriffs, constables and deputies from practicing law or forming a partnership with an attorney.

Oppose

SB 1186: Criminal street gang database; appeal: Would require a local law enforcement agency to provide notice to a person (and their parent or guardian, if under 18) before designating them as a suspected gang member, associate or affiliate in a shared gang database, and would allow the notified individual to appeal that designation.

SB 1419: Highway video surveillance; prohibited: Would prohibit the state and its agencies from conducting video surveillance on controlled access highways and sidewalks, and would repeal statutes authorizing and regulating photo enforcement.

HB 2465: Search warrants; procedures; notifications: Would amend statutes related to search warrants, including requiring judges to notify subjects of an ex parte order for a pen register or trap and trace device, and prohibiting a law enforcement agency from obtaining, using, copying or disclosing information related to a subscriber or customer from a provider of an electronic communication service or remote computing service without a warrant.

HB 2591: Peace officer; liability; unlawful act: States that a peace officer who, in the performance of their duties or through the failure to intervene, deprives another person of any individual right is liable to the injured party for legal or equitable relief, and that qualified immunity is not a defense to this liability.

HB 2618: public nuisance; noise; evidence: Would require that prosecution for a public nuisance that involves noise must include an accurate recording and measurement of the noise by a peace officer or code enforcement officer.

HB 2764: sentencing; concealed weapons permit; surrender: Would require convicted felons to surrender their concealed weapons permit if their conviction makes them ineligible to possess it. If the felon does not surrender the permit, the bill requires the court to revoke it and the Department of Public Safety to locate the defendant and seize the permit.

For further information and updates on these and other current bills, please check the Arizona Legislature’s bill status inquiry page at https://apps.azleg.gov/BillStatus/BillOverview, or visit the APA website at www.azpolice.org. PLEA

During contract negotiations, rumors tend to get out of control. Local media outlets have even heard some of these rumors and have called the PLEA Office for verification. Kind of funny, kind of not, I guess, but this is how it seems to be every negotiation cycle. We have not heard of any new rumors beyond the ones already addressed in a membership update video, but if you happen to hear anything that sounds questionable, please do not hesitate to call the office so we can clear things up. As of this writing (in the first week of February), we have yet to reach the financial portion of contract proposals. Your PLEA Negotiation Team is working diligently with the City’s negotiators to find common benefit within proposals from both sides, and we are having some success. Sometime in March, PLEA Chief Negotiator Darrell Kriplean will be able to provide more information to the membership regarding the City’s proposals, and he will also schedule the contract ratification meetings, where we can discuss the proposed contract.

Your PLEA Negotiation Team is working diligently with the City’s negotiators to find common benefit within proposals from both sides.

The legislative session is also underway at the Arizona State Capitol. The Arizona Police Association (APA) is working hard to ensure that PLEA members continue to have a strong Peace Officer Bill of Rights and that legislators understand the needs of law enforcement professionals in Arizona. APA Executive Director Joe Clure keeps the APA membership aware of the legislative proceedings while bringing attention to the bills that may or may not benefit or affect law enforcement and public safety.

PLEA will be taking part in discussion of new federal legislation for law enforcement, and I will keep the membership updated as to how the laws will affect us.

Finally, I want to say farewell to PLEA Secretary Franklin Marino. Frank retires at the end of March. During his police career, Frank has served PLEA members for more than 20 years as a PLEA representative and Executive Board member. We will miss the institutional knowledge Frank has, and his uncanny ability to remember everything since 1963. We wish Frank and Dena the best in their retirement.

As I’m typing away on my keyboard, I’ve got a smile on my face, a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye as I realize that this will be my last official writing for an organization I’ve been part of for the past 26 years. As a child growing up, I would never have imagined that half a century later, I’d be 2,500 miles away from the place I envisioned living my life, and working in a profession that was a playtime activity based on Adam-12. Events that occurred in my life and the lives of family members led to an Arizona vacation, then a decision to leave New Jersey and move to Phoenix, which paved the way for me to become a Phoenix police officer.

As I’m typing away on my keyboard, I’ve got a smile on my face, a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye as I realize that this will be my last official writing for an organization I’ve been part of for the past 26 years. As a child growing up, I would never have imagined that half a century later, I’d be 2,500 miles away from the place I envisioned living my life, and working in a profession that was a playtime activity based on Adam-12. Events that occurred in my life and the lives of family members led to an Arizona vacation, then a decision to leave New Jersey and move to Phoenix, which paved the way for me to become a Phoenix police officer.

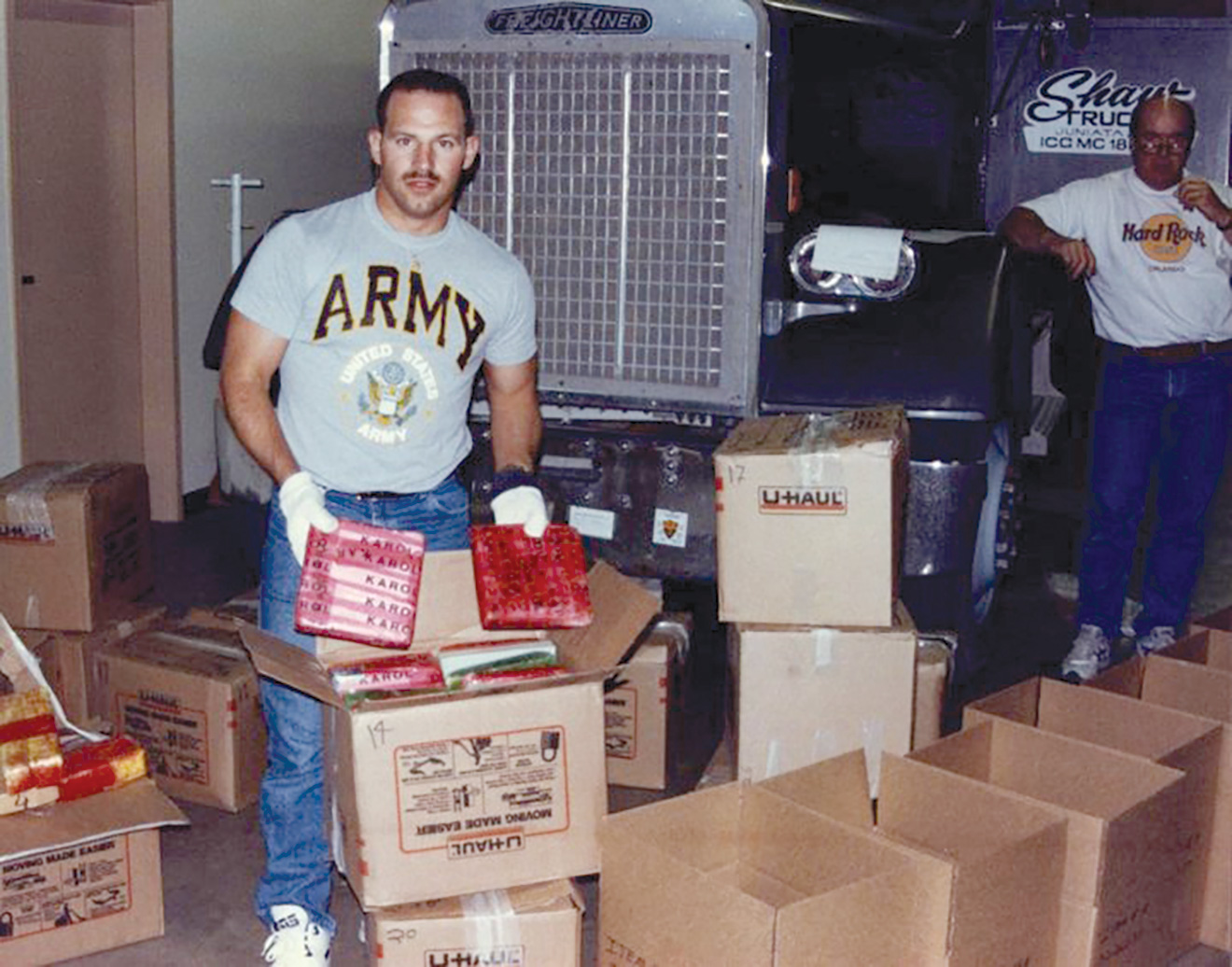

After visiting Arizona twice in 1988, I tested for Scottsdale in the spring of 1989. I completed my oral board and never heard back from them. Arizona became my new home that fall, and a year later, in 1990, my Military Police unit was activated for Desert Shield, which became Desert Storm. The deployment changed my life course and reaffirmed my goal of becoming a police officer. In November 1991, I finally had the opportunity to test for the Phoenix Police Department, which was considered the premier agency in Arizona. Instead of attending my 10-year high school reunion in New Jersey, I took the written test with hundreds of others at the old Civic Plaza and proceeded to the Academy for my physical fitness test. The MCSO deputy who scored my sit-ups said I did not complete the required number. Since I was on active military duty, my first thought was to challenge him, because I worked out daily and made it a point to be able to pass the PT test with well above the minimum reps for both push-ups and sit-ups. However, the soldier in me knew a challenge could work against me, so I retested in January 1992, passing with no issues. Then, Phoenix had a hiring freeze, so I tested with Chandler and the Pima County Sheriff’s Office, only to be put on waiting lists.

It has been an honor and privilege to serve the membership over the past 20 years, working to right wrongs and fighting the good fight.

By September 1992, Phoenix began hiring again, but I opted to use my GI Bill benefits to attend college. My thought process was that secondary education would make me more competitive in the hiring process. In the spring of 1994, I tested again and was hired in late September. I started the Academy on October 3, 1994, with Class 265, graduated on January 13, 1995, and was assigned to 500 to start the FTO program. 500 would be home for most of my career; I spent my first seven and a half years on second shift, including four and a half years on an FTO squad. During my time as an FTO, former PLEA President Ken Crane and I worked as partners, and he persuaded me to get involved with PLEA as a representative. The furthest thing from my mind when I became a cop was any aspiration of being a labor representative; however, as it has been said, “Everything has a reason for happening,” and happen it did. During that same time period, another life event occurred: I met my wife, Dena. When we started dating, she was a single mother, and when we decided we were going to get married, I opted to go to third shift to spend more time with her and my daughter and son, which is where I spent the next nine years of my career. It’s enough of a challenge raising a family when you’re a cop working holidays, getting home late due to holdover and missing family events because of shift conflicts or the inability to get time off. However, the move allowed me to attend recitals, concerts and other school events, T-ball and soccer games, and scouting events. I’m grateful for that family time we shared.

In 2009 I was appointed to the PLEA Board to fill a vacancy, then ran for and was elected to a trustee position. I became chair of the Board within a year, and in 2011, former PLEA President Joe Clure asked me to run for secretary, which I did. That August, I moved into a full-time release position in the PLEA Office. When you combine the challenges of being a cop and raising a family with being a police labor representative, it’s a whole different game when you are actively involved in the organization, and that compounds when you become a Board member. Your cellphone becomes an appendage, with what can seem like nonstop calls, text messages and emails coming in at all hours, regardless of whether you’re working, on your days off or on vacation in the mountains. Why is that? It’s because you are a resource for people seeking your guidance and wisdom in their moment of need. It also means callouts in the middle of the night or on weekends and days off while taking standby.

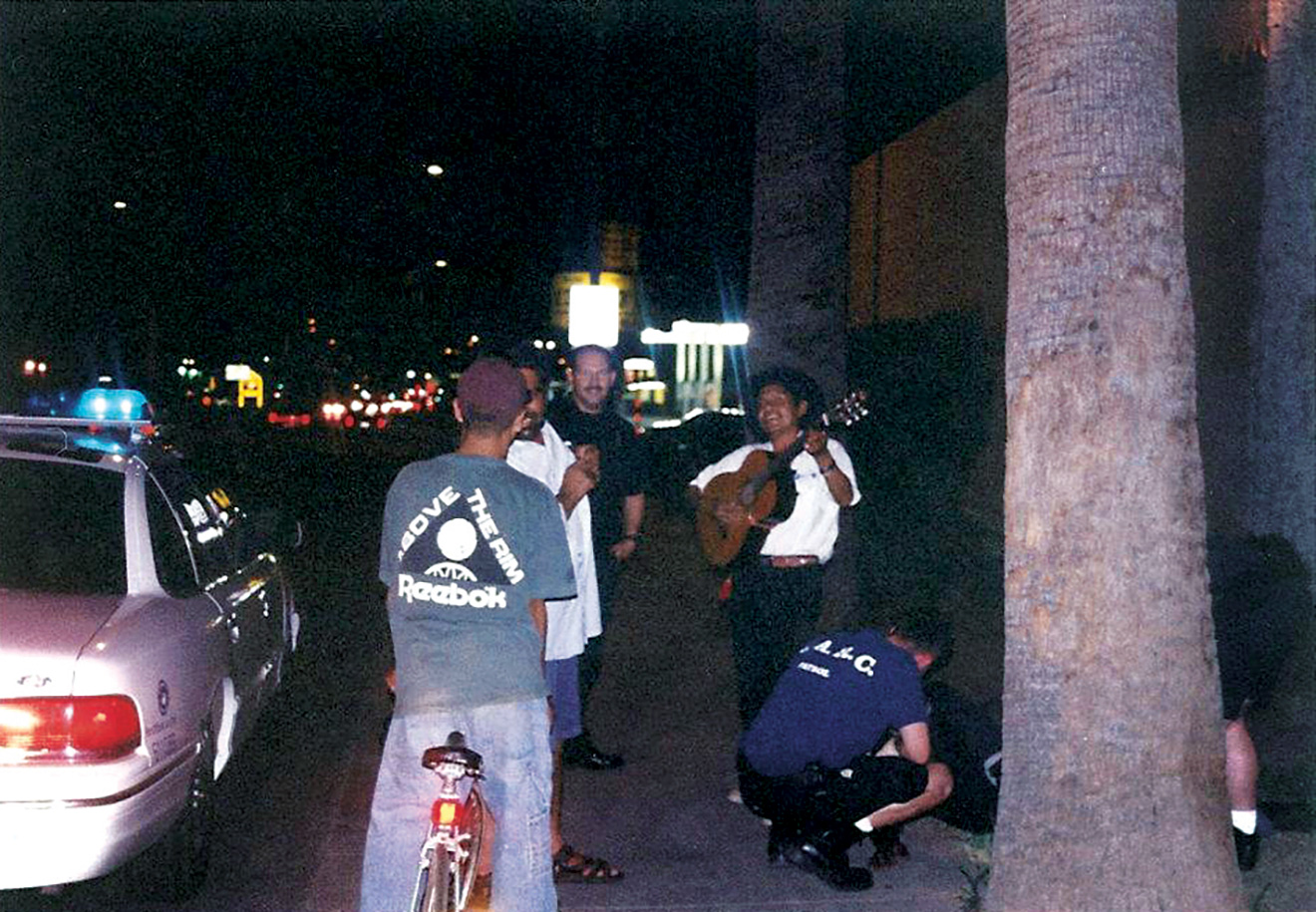

In June 2012, I spent two weeks assigned to 600 after the first Goldwater injunction; then, in May 2013, I went back to 500 after the second one. After almost a year and a half, I opted to go to 700 in the 2014 rebid and stayed there for nearly two years, until the Arizona Supreme Court overturned the Goldwater injunction in September 2016 and I returned to PLEA. During my time in 700, I worked the former 52 and 53 areas, where I had cut my teeth and spent most of my career as a beat cop. I felt comfortable and confident working in my old backyard. The most challenging three years and four months of my stint as a PLEA Board member were during the Goldwater injunction, because I remained on a Patrol squad and did not make it back to the office. In addition to working 10-hour-plus shifts, I was handling PLEA business prior to and after my shift, as well as on my days off. Having said that, if I didn’t have a full-time release position, I would have opted to stay in Patrol, because it’s what I loved doing, even though it has drastically changed within the past few years. Despite the challenges during those years, there were some good times, and I got to push my limits as a street cop thanks to another partner, Kevin Wilson, who, like me, became a PLEA rep and Board member. We got into several potentially dangerous situations during the time we worked and rode together, but we made numerous felony arrests, including some that were tied to very complex cases. We did not make any excuses for pushing the limits; that’s what happens when you’re a street cop at heart and love the thrill of the hunt and chase.

I never had the desire to promote. Between my deployment to Saudi Arabia during Desert Storm and my active-duty assignment on the Task Force, I had my fill of supervising, including a few problem children who taxed my patience. During my time on the Department, I worked for a number of good supervisors, but I also worked for my share of bad ones. I saw the flaws of a system that promoted test-takers versus leaders and those with the solid tactical base of a street cop. Granted, I could have become part of the solution by promoting, but for me, it was more challenging and rewarding to become part of the solution as a PLEA rep. That gave me the ability to hold both bad officers and bad supervisors accountable for their actions, whether it was a simple mistake of the heart or blatant misconduct. Bad officers got walked out the door, while officers who made mistakes, or were alleged to have made mistakes but didn’t, were vilified at Use of Force and Disciplinary Review Boards or meetings with the Police Chief. Bad supervisors or supervisors who bullied their troops were also dealt with, while good supervisors who supported their troops, sometimes against the will of their superiors, were rewarded. Speaking of rewarding, going head-to-head and taking to task a bullheaded, overzealous former “Chief of Police” was one of the more rewarding things I did as a rep. As I always tried to explain to supervisors and managers who were willing to listen, it wasn’t personal; it was business, and it shouldn’t interfere with working together for a common cause and goal, which we signed up for when we became cops.

When I was hired, Phoenix was the police department everyone wanted to work for but couldn’t. Hiring standards were well above AZ POST minimum; the Academy had a paramilitary format that challenged us and weeded out those who couldn’t meet standards. Not everyone made it through the FTO program, and not everyone who managed to go solo was able to keep up with the pace afterward and complete probation. While we worked hard and consistently got our asses handed to us in terms of call volume combined with holdover on the weekends due to multiple violent crime scenes, we had fun doing it. We were still allowed to do police work, and it involved going after people who committed crimes and putting them in jail, sometimes after a vehicle or foot pursuit. Pushing the limits to the edge was common and, thankfully, most of the supervisors I worked for and under were street cops at heart and did what they needed to do to make sure overzealous commanders didn’t come after us.

While police work itself has remained relatively unchanged, technology has affected it positively and negatively. When I came on, our issued Glocks did not have weapon light rails, and our gun belts, holsters and accessories were heavy, synthetic leather. Most of us carried a rechargeable Maglite or Streamlight that doubled as an impact weapon, and while some of us were designated as shotgun operators, we didn’t have Tasers or patrol rifles. Pagers were common and some of us had cellphones. Our patrol vehicles were Chevrolet Caprices, but they had halogen rotator emergency lighting and no reflective markings. They did have Mobile Data Terminals, which allowed us to receive and disposition calls, run records checks on people and vehicles, and complete false alarm and field interrogation cards; however, they had less functionality than the most basic smartphones of today. We either handwrote our reports and turned them in at the front desk, or dictated them to a live secretary or a recorder called the Voicewriter for eventual transcription and entry into PACE, which was much easier to navigate than RMS. Booking paperwork was filled out by hand and could be done on the hood or trunk of a patrol car at the scene before heading to the “Horseshoe” at the Madison Street Jail, where it would be reviewed by a police assistant before you turned your prisoner over to MSCO personnel. Over the years, technology made some processes easier while hamstringing and lengthening others.

Caprices gave way to Ford Crown Victorias and vehicle-mounted laptops that were difficult, if nearly impossible, to remove to get the intended function out of them. Every marked patrol vehicle had a less-lethal stun bag shotgun, and each squad had designated Taser operators until everyone in Patrol was issued a Taser. 2001 marked the implementation of the Patrol Rifle Program, full-sized 20-inch-barrel “politically correct” Colt AR15 HBAR Sporters. It would take a few years for common sense to work its way into the program, upgrading to Colt LE6920 Carbines with 16-inch barrels and collapsible stocks. In 2005, we tested our first Tahoe with much-improved emergency lighting and internal gun racks. As the Crown Victoria was slowly phased out, Tahoes were integrated into the fleet. We used the Chevy Impala purely for cost savings and to get the fleet modernized. Gun racks were moved to the front of the Tahoes for easy access, while laptops slowly improved. Eventually, we had console-mounted printers and scanners for use in conjunction with TRACS, which is how we wrote crash reports and issued citations and exchange cards. In 2013, after over a decade of testing and evaluating various emergency lighting packages, we finally had 100% LED emergency lighting on our Tahoes. We continued to improve the interior setups, eventually convinced City bean-counters that an all-Tahoe fleet would save money in the long run based on vehicle life cycle costs, and stopped purchasing Impalas and the reintroduced Caprice. RMS replaced PACE, and many of us still believe PACE was a much better system despite it living on borrowed time. Some of us still affirm that a fraction of the money dumped into RMS could have prolonged PACE, but the City and Department hate to admit when they’re wrong, as they’ve been with the entire RMS fiasco. Body-worn cameras went citywide from a pilot program in Maryvale and continue to prove what we knew before we had them: Phoenix police officers are professional, do a good job and use reasonable force when necessary to conduct our mission. They also show that we deal with violent individuals on a more frequent basis than we ever have and resort to lethal force when there are no other options available, despite the rhetoric heard from anti-police activists and members of our City Council.

Caprices gave way to Ford Crown Victorias and vehicle-mounted laptops that were difficult, if nearly impossible, to remove to get the intended function out of them. Every marked patrol vehicle had a less-lethal stun bag shotgun, and each squad had designated Taser operators until everyone in Patrol was issued a Taser. 2001 marked the implementation of the Patrol Rifle Program, full-sized 20-inch-barrel “politically correct” Colt AR15 HBAR Sporters. It would take a few years for common sense to work its way into the program, upgrading to Colt LE6920 Carbines with 16-inch barrels and collapsible stocks. In 2005, we tested our first Tahoe with much-improved emergency lighting and internal gun racks. As the Crown Victoria was slowly phased out, Tahoes were integrated into the fleet. We used the Chevy Impala purely for cost savings and to get the fleet modernized. Gun racks were moved to the front of the Tahoes for easy access, while laptops slowly improved. Eventually, we had console-mounted printers and scanners for use in conjunction with TRACS, which is how we wrote crash reports and issued citations and exchange cards. In 2013, after over a decade of testing and evaluating various emergency lighting packages, we finally had 100% LED emergency lighting on our Tahoes. We continued to improve the interior setups, eventually convinced City bean-counters that an all-Tahoe fleet would save money in the long run based on vehicle life cycle costs, and stopped purchasing Impalas and the reintroduced Caprice. RMS replaced PACE, and many of us still believe PACE was a much better system despite it living on borrowed time. Some of us still affirm that a fraction of the money dumped into RMS could have prolonged PACE, but the City and Department hate to admit when they’re wrong, as they’ve been with the entire RMS fiasco. Body-worn cameras went citywide from a pilot program in Maryvale and continue to prove what we knew before we had them: Phoenix police officers are professional, do a good job and use reasonable force when necessary to conduct our mission. They also show that we deal with violent individuals on a more frequent basis than we ever have and resort to lethal force when there are no other options available, despite the rhetoric heard from anti-police activists and members of our City Council.

I have many people to acknowledge and thank for what I have achieved. First and foremost, I give thanks to God for looking out for me every step of the way during this amazing journey, but there are countless others, many of whom I’ve alluded to in the articles I’ve written over the years. From childhood into adulthood, there were many cops who left impressions on me. They include cops I encountered growing up, the beat cops who’d stop in at my dad’s shop and a neighbor who was a patrol sergeant on our township police department. There were other cops from various agencies I met and worked with after my enlistment in the Army National Guard and service in two different Military Police units, and I met others during training and activations. During my three-plus years of active duty on the Arizona National Guard’s Joint Counter-Narcotics Task Force, I met more cops and federal agents. Those experiences and the knowledge I gained firmly set the wheels in motion for a major life and career change. As I was laying the groundwork and contemplating that change and the decision to become a police officer, there was unconditional support from my immediate and extended family and friends. My parents, sisters, grandmothers, aunts, uncles and cousins were there for me through the entire process and beyond. Longtime family friends and personal friends, including some from high school, others I met afterward, my “Whiskey Bravos” and other Army buddies, some of whom served or continue to serve in law enforcement, have all been a part of my support network. I met my wife when I had five years on the job and she has been there through thick and thin. She and my daughter and son have always understood the complexity of the job and supported and encouraged me during the best and worst times of my career since they’ve been a part of my life.

The past 26 years have been awesome, and I’m glad I had the opportunity to be part of a great law enforcement agency before it was dismantled by spineless politicians and managers who lost touch with their street cop roots. I always tried to do the right thing for the members of the community whom I ultimately served, and I had the honor and privilege to work with some amazing cops over those years — some who are still with us, some who left this Earth too soon, others who have retired, and still others who are doing bigger and better things at other agencies because of the skills they gained working for Phoenix. It has been an honor and privilege to serve the membership over the past 20 years, working to right wrongs and fighting the good fight when necessary. Having said that, it also has been an honor and a privilege to have served as an elected Board member under four different PLEA presidents over the past 12 years. While we may have had philosophical differences at times, we all worked together for the greater good of the membership. Farewell, my friends and colleagues; it has been a helluva ride! 6024 is 10-7!